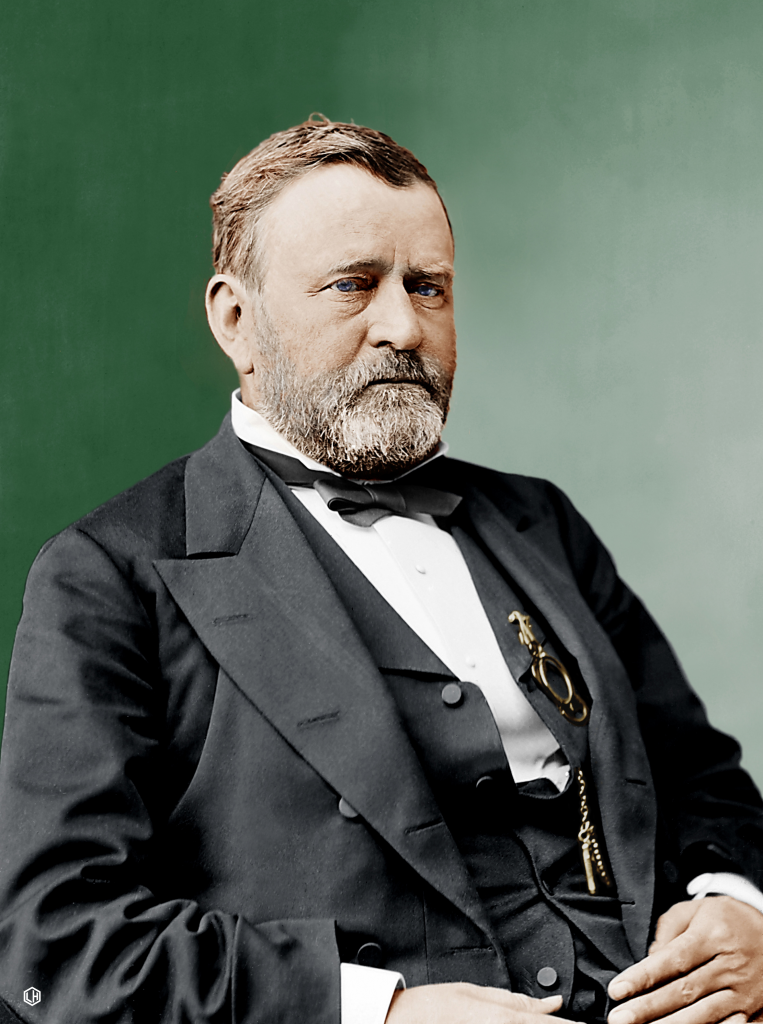

Before he was a military general, before he was a president, Ulysses S. Grant was a humble Ohio resident. Born Hiram Ulysses Grant into a working-class family in a small Ohio village in 1822, the future leader only reluctantly went to West Point – a former fort turned home of the United States Military Academy – where he graduated in the middle of his class.

As a military man, he saw his first field experience in the Mexican War (1846-1848). At the outbreak of the Civil War, Grant was appointed by the Governor of Illinois to command a volunteer regiment, and by September 1861, he had risen to the rank of brigadier general. President Abraham Lincoln appointed him General-in-Chief in March 1864, and Grant commanded the Union forces at the Battle of Appomattox Court House on 9 April 1865 – one of the last battles of the war. After Confederate General Robert E. Lee’s aborted attempt to avoid bloodshed, minor skirmishes ensued, and Lee finally surrendered to the Union army, cementing Grant’s legacy.

Viewing Grant as a figure who could unify post-war America, the Republican Party nominated Grant as their presidential candidate. Grant went on to win the elections in 1868 and 1872, managing a challenging process of national reconstruction amid serious financial difficulties, persistent opposition and recurrent violence against recently freed slaves in the South.

His life after the presidency was just as eventful, however. During this period, Grant travelled the world on a diplomatic tour – the first US president, current or former, to circumnavigate the globe. Included among stops were Europe, Africa, India, the Middle East and Asia where Grant met with Queen Victoria, Pope Leo XIII, Otto von Bismarck, Li Hongzhang and Emperor Meiji, and became the first US president to visit Jerusalem and the Holy Land. Grant also made a little-reported visit to Macao. According to Grant’s own records, it did not go exactly as planned.

Grant gets the red carpet treatment

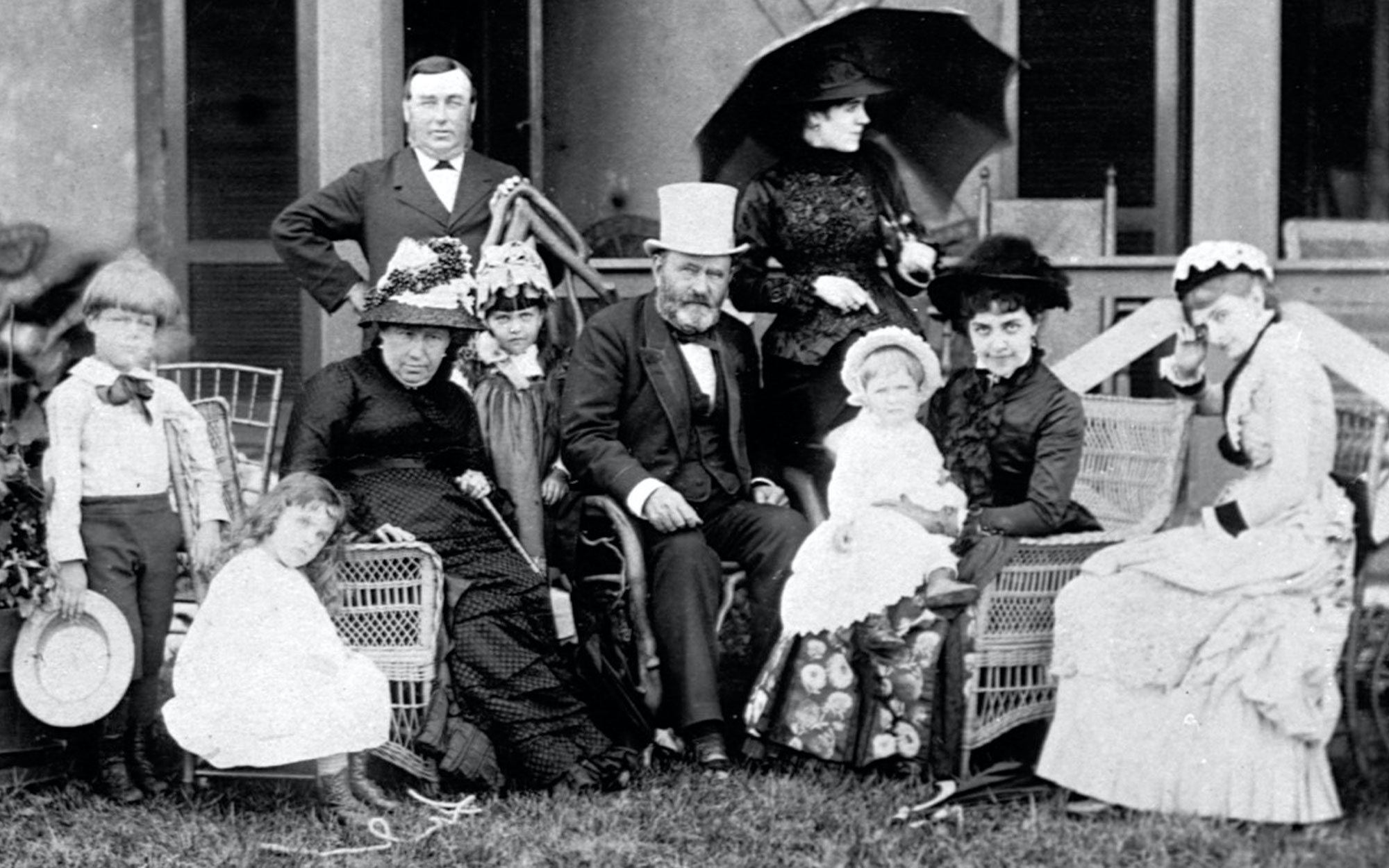

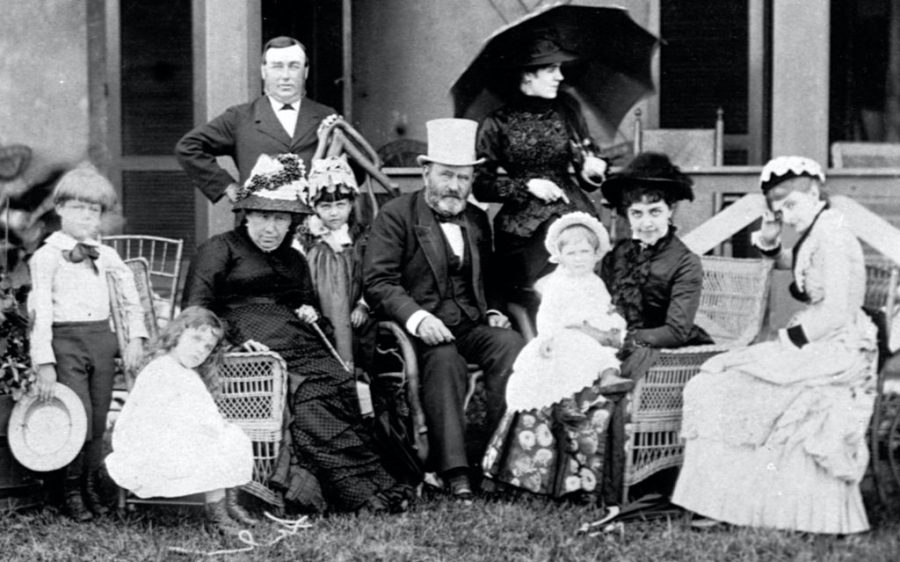

In the Ulysses Grant Presidential Library at Mississippi State University, other than the countless personal records of the Civil War and the presidential years, another much more cosmopolitan theme stands out in hundreds of texts, reports, letters, discourses, correspondence and photos: Grant’s lengthy world tour from 16 May 1877 to 20 September 1879.

The world tour generated immense US public interest, at least among the urban readers of major newspapers and magazines. It also later became an editorial success when John Russell Young – a New York Herald journalist, diplomat and future Minister to China and Librarian of Congress – who accompanied Grant’s party on the journey, assembled his daily notes into two beautifully illustrated volumes, followed by other books published in 1879-80 by W. H. Hicks, L. T. Remlap, J. F. Packard and James Dabney McCabe.

The latter wrote in his fully illustrated A tour around the world by General Grant: “His journey was the most remarkable ever made by any human being. Wherever he went, he was received by people and sovereigns with royal honours, and was in all respects the most honoured traveller that ever accomplished the journey around the world.”

Everywhere he went, Grant was welcomed by emperors, kings, sultans, presidents, heads of state and colonial rulers, and was put up in palaces and official residences.

Grant met Queen Victoria at Windsor Palace, King Christian of Denmark in Copenhagen, the Austrian Emperor Franz Joseph I in Vienna and the German Emperor William I in Salzburg. He held talks with Chancellor Bismarck, was received by Czar Alexander II in St. Petersburg, and visited Pope Leo XIII and King Umberto in Rome. He was also particularly welcomed by the kings Leopold II of Belgium, George I of Greece and Alphonse XII of Spain.

Grant was especially surprised by his visit to Portugal. In Lisbon, the former president was welcomed by King D. Luís. On the day following his arrival, Grant was invited as the guest of honour at the king’s royal birthday. There he refused to be awarded the highly sought Portuguese Grand Cross of the Tower and Sword decoration, instead only accepting the gift of a rare copy of the king’s personal translation of Shakespeare’s Hamlet into Portuguese.

Outside Europe, Grant was also welcomed with the most fantastic celebrations. The last Sultan of the Ottoman Empire, Abdul Hamid II, received Grant in the Topkapi Palace in Istanbul and offered him two Arabian stallions. The Khedive of Egypt, Isma’il Pasha, hosted him in the luxurious Kas El-Gawhara palace in Cairo and provided a steamship for his travels on the Nile to Luxor, Karnak, Aswan and Memphis.

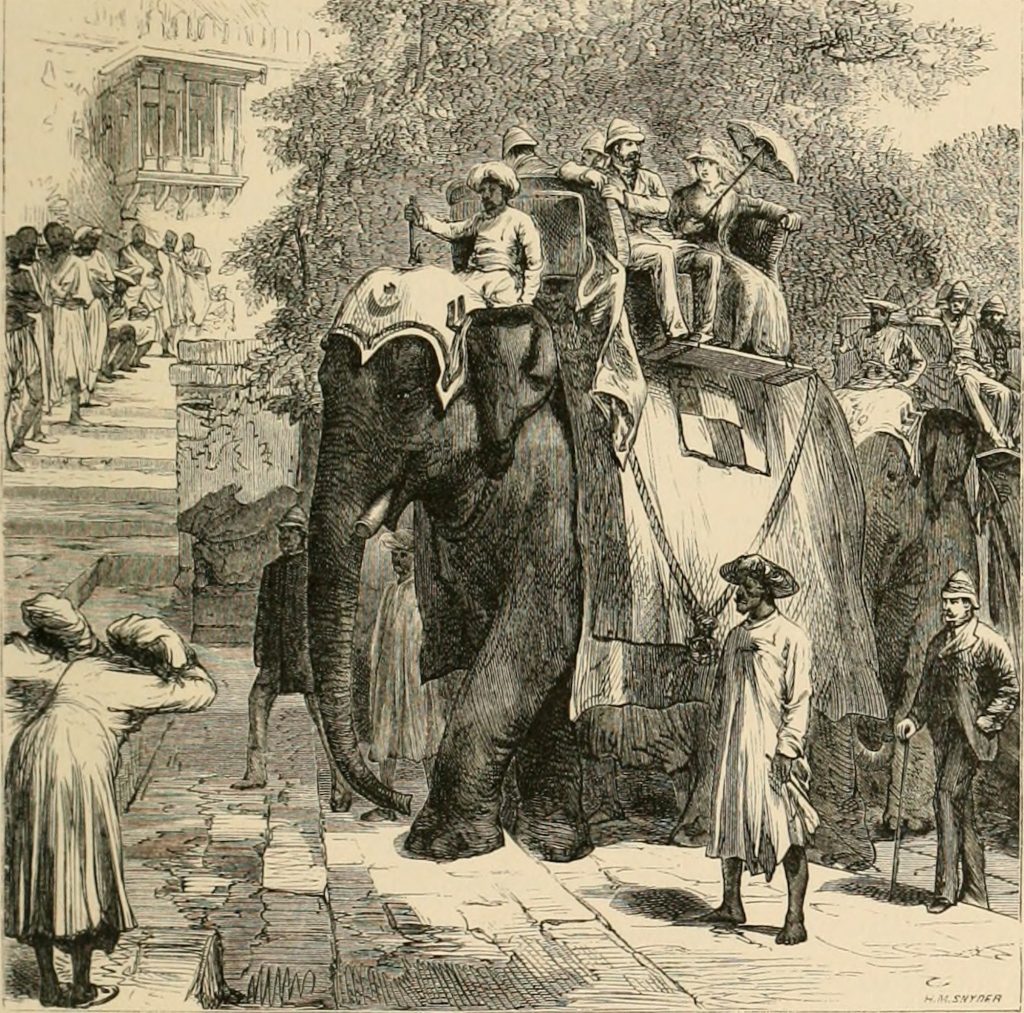

During his month-long visit to India, Grant met the Viceroy Lord Lytton, several provincial governors and the Maharaja of Jeypore. In Rangoon (now Yangon, formerly the capital of Myanmar) Grant was received and lodged in the governmental house of the British colonial chief commissioner, Charles Umpherston Aitchison.

In Siam (Thailand), he met and spoke with King Chulalongkorn. The British colonial governor of Singapore received Grant with formal and military honours. Later in the voyage, he was lodged in the governmental palace of the French governor of Cochinchina, now Vietnam, the rear-admiral Louis Jules Lafont.

In his two stays in Hong Kong, Grant dined, celebrated and spoke with everyone from the British governor, John Pope Hennessy, to prominent businessmen. His Hong Kong stays included meetings with two of the most influential Chinese leaders, the lawyer Ng Choy (Wu Ting-fan), future minister of foreign affairs and briefly acting prime minister in the early years of the Chinese Republic, and Tong King-sing, entrepreneur, chief ‘comprador’ of the Jardine Matheson Company, author and future general manager of the China Merchants Steam Navigation Company in Shanghai.

Parades, official visits and diplomacy in Asia

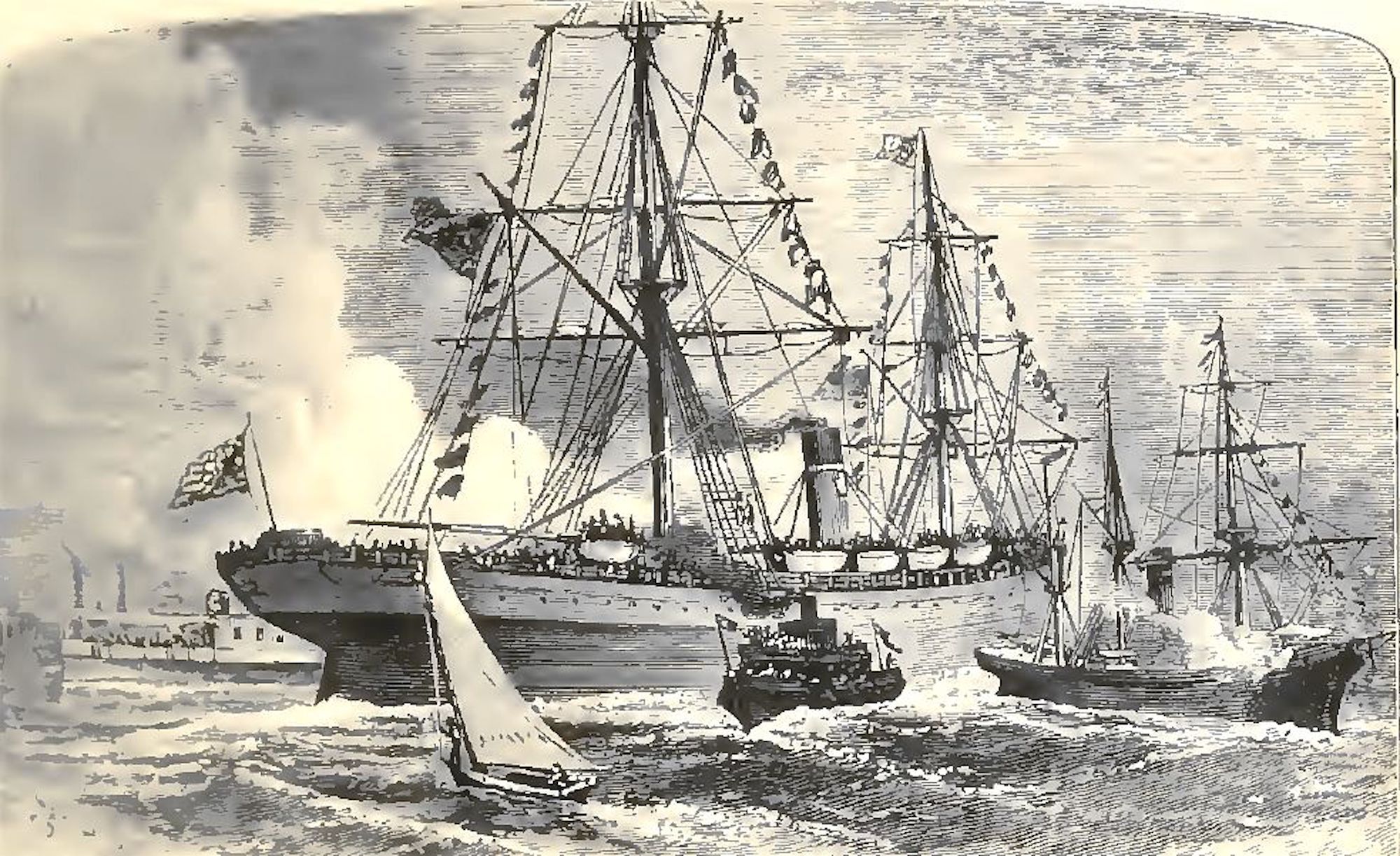

Despite all these receptions, nowhere in the world did Grant receive such extraordinary public and official welcomes as in China. Arriving in Canton (today known as Guangzhou) on 5 May 1879, Grant was received by a crowd estimated by some of close to 200,000 people that had waited hours for the arrival of the USS Ashuelot steam gunboat.

Over four days, Grant engaged with the viceroy and other authorities and frequented countless public ceremonies. His wife, Julia Grant, the “first lady” in US history to write her memoirs, recorded with some displeasure: “I was greatly disappointed in my visit to Canton, as I had to see people nearly all of the time and did not have an opportunity to see anything of the city”.

It was the same from 13 May in Swatow (Shantou), then in Amoy (Xiamen), and then during the six days Grant spent in Shanghai, where the city authorities honoured him with a night parade lit up by torchlights and fireworks. Thousands of people followed the procession.

These great public and official manifestations were repeated in Tientsin (Tianjin), and upon Grant’s arrival in Beijing on 3 June. In the capital, he was immediately engaged in substantial talks with the Viceroy of Tientsin General Li Hongzhang and the Prince-regent Kung (Gong), the practical head of state during the nonage of Emperor Guangxu, who was only seven years old at the time of Grant’s visit. Kung asked him to intervene in favour of China in the conflict with Japan regarding the Ryūkyū Islands. Grant accepted and expressed respect for the territorial integrity of China several times in public ceremonies, arguing against European colonial interference in China at the same time.

After arriving in Japan on 21 June, Grant twice met the Meiji Emperor and suggested he create a Sino-Japanese commission to solve the conflict. Later, on his departure from Japan, on 3 September, in the farewells to the Emperor, Grant told him in a written speech: “I may add that nothing would give me more pleasure than to be able to carry back to my own country to which I am about to sail, the knowledge that peace between China and Japan had been assured”; It didn’t happen. Even so, in China and Japan, as everywhere worldwide, Grant was officially received as a universal military hero and dignitary.

There was, however, one – and only one – exception: Macao.

The cold shoulder

Grant arrived in Macao early in the afternoon of 9 May. The USS Ashuelot was saluted by 21 shots from the Mont Fortress batteries, which the American ship answered.

After waiting more than an hour, a Portuguese military officer came on board to inform Grant that the Macao Governor, Carlos Eugénio Correia da Silva, was sick and unable to receive him. The illustrious visitor decided to descend onto land where he was greeted by 2-3,000 people, mostly Chinese, and found shelter in the Hotel Macao.

Unlike all his other stops, in Macao, Grant gave no speeches, attended no official ceremonies and was not invited to lodge in a palace. It was Friday and raining. After dinner, Grant visited the Chinese bazaar and played fantan – the popular gambling game – in one of the gambling houses, attracting the curiosity of hundreds of Chinese residents.

On Saturday morning, he visited the Camões Garden and grotto guided by the owner of the famous Garden House, commander Lourenço Marques, who had a special triumphal arch built to greet the former president. Several influential Macanese entrepreneurs and members of the municipal power, the Leal Senado, accompanied Grant on this excursion.

The Ashuelot then left for Hong Kong around 10-10:30 in the morning with Grant and his entourage onboard. At noon, the ‘sick’ governor attended a solemn mass in full military dress in honour of the Holy Virgin. The official bulletin of the Macao government also revealed that at 5 pm, the governor, definitively not sick, opened the regular weekend musical performance of the military band in the St. Francis Gardens.

Certainly, the Portuguese colonial governor was not unwell. So why did Grant get snubbed in Macao? It was likely because he didn’t know what to say. The governors sent from Lisbon in the last decades of the 19th century knew very little about Macao and ignored China.

Fortunately, the people of Macao picked up the slack, welcoming the travelling party with signs and pageantry, and showing the Grants some of the city’s sites.

In her ‘Personal Memoirs’, Julia Grant recalled visiting a licensed gambling house and the private garden of a wealthy Portuguese citizen. She also highlighted Macao’s natural beauty and made passing mention to a warm welcome from the people of Macao.

“Macao is beautifully situated on a high promontory almost surrounded by water,” wrote Julia Grant. “The General walked out in the rain to see the place and saw ‘Welcome to General Grant’ written over many doors”.

Even if the governor gave the Grants a frosty reception, the city at least left an impression on the party – just not one that might stand out from stays in luxurious palaces in Cairo and Istanbul.

“Diary on Macao”, in Grant, Ulysses S. The Papers of Ulysses S. Grant. Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press, 2008, vol. 29, p. 82.

On the 9th left Canton and descended the river amidst the booming of cannons from Chinese gunboats and forts all along the way to the Ancient Portuguese town of Macao. This was the first settlement on Chinese soil held and governed by a foreign power. Macao is beautifully situated on a high promontory almost surrounded by water. The view to the sea is cut off by numerous islands of considerable elevation. It was a most flourishing city until the Coolie trade was put a stop to by more civilized and more humane nations. Now it is in a languishing condition and derives a large part, possibly the largest part of revenue, from licensed gambling. It is to be hoped that the Chinese will retake this place.

Spent the night of the 9th of May at Macao Hotel, visited one of the licensed gambling houses and the following morning took a short run through the private garden of a wealthy Portuguese citizen. The garden is on a high hill overlooking the city and commands a fine view of the surrounding country.