During Macao’s firecracker era, when a sizable segment of the population spent much of the 20th century crafting explosive pyrotechnics for export, Iec Long factory in Taipa was a major employer from 1926 until its closure in 1984.

In December 2022, however, the Cultural Affairs Bureau (IC) reopened the abandoned complex, which has been transformed into a fascinating industrial heritage site that shines a light on this often overlooked chapter of Macao’s history.

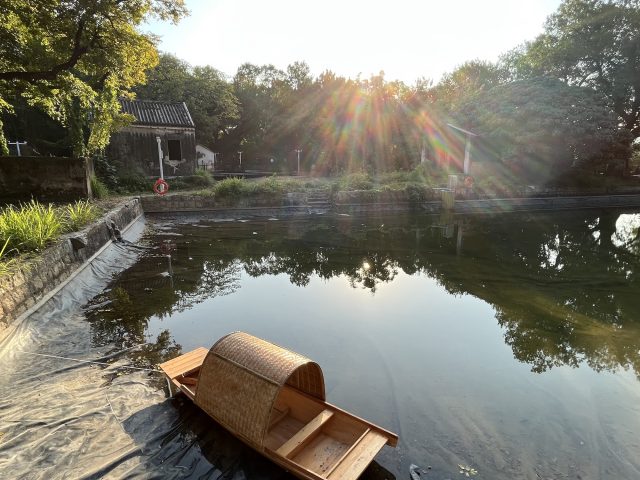

Visiting the new landmark serves as a reminder of the city’s manufacturing history. You’ll walk past a 400-metre-long walkway through the old fuse-glueing and firecracker-crimping workshops, continue along a pond and then enter an exhibition hall, where you can learn how firecrackers were made and the industry’s development.

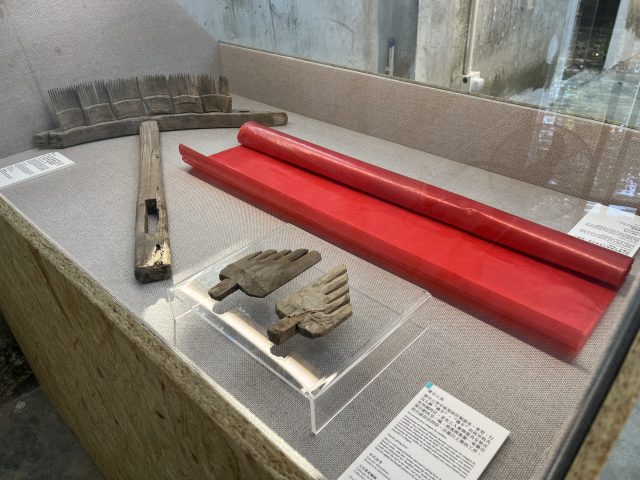

Along the way, you’ll also encounter an array of artefacts – think old tools, the factory’s original wood and stone signboard, and Iec Long’s firecracker packaging – as well as historical photographs and interactive video demonstrations.

Local author Albert Lai had been looking forward to Iec Long’s restoration for more than a decade. The 73-year-old, who grew up making firecrackers and has written several books about the industry, took on the role of an academic advisor for the new Iec Long exhibition. He also lended photographs from his personal collection.

“For tourists visiting Taipa, after exploring the Cotai Strip, Rua do Cunha and the Taipa Houses, I hope they also come to see Iec Long,” Lai says. “After all, it has had such an impact on Macao.”

Lai says he is relieved the factory will serve as a monument to Taipa’s firecracker heritage, and will add to the growing list of efforts to preserve history, including books and art exhibitions.

Growing up in the firecracker era

While China’s history with firecrackers dates back some 2,000 years, Macao didn’t enter the fray until the late 19th century. By the 1920s and up until the 1970s, firecrackers were one of Macao’s top three exports, alongside incense and matchsticks.

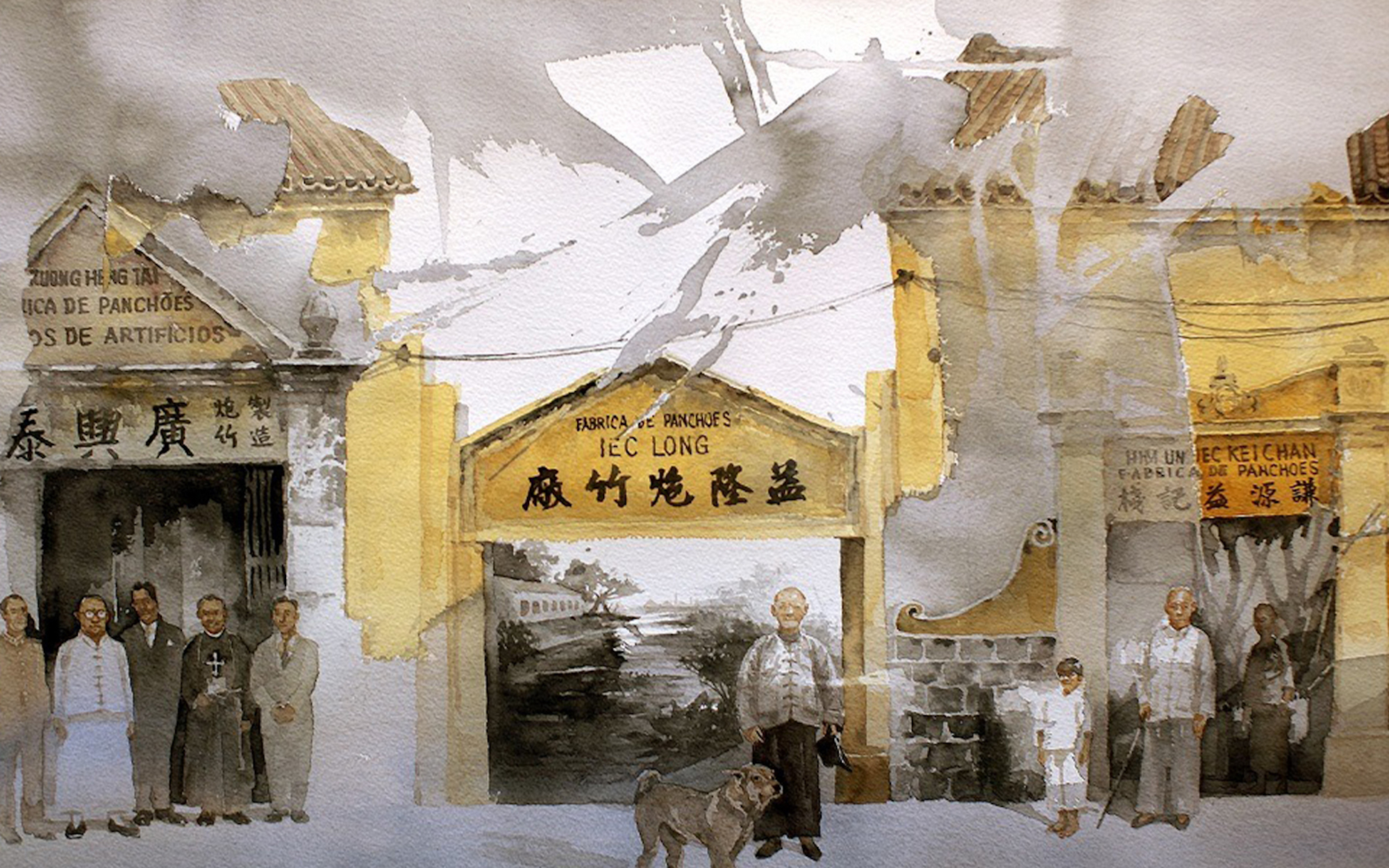

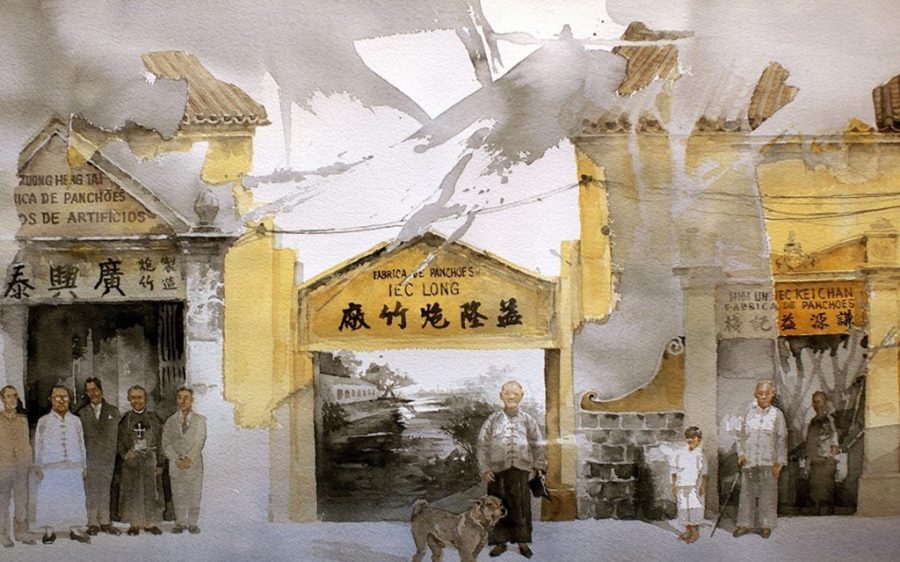

Six firecracker factories existed in Taipa back then, namely Kwong Hing Tai (the largest), Iec Long (the longest running), Him Un, Kwong Yuen, Him Son and Po Sing.

The Macao Peninsula had firecracker factories, too, at the beginning of the industry’s boom. But a disastrous explosion in 1925 at the Toi Shan factory – which killed more than 100 people and left 300 more injured – led officials to limit the bulk of production to Taipa.

When Lai was a child in Taipa, making firecrackers was the main source of income of almost every family he knew. Both adults and children worked for the factories, either on-site or from home. While Lai recalls this period of his life as tough, his memories are tinged with nostalgia.

He speaks of learning how to braid strings of firecrackers together by their individual fuses at age 6, working alongside his mother, brother and sister at home in Taipa (his father had moved to Hong Kong to find work).

“We worked in front of our own small tables, so our firecrackers wouldn’t get mixed,” he says of his 1950s childhood. “During the night time, we had to push the tables closer together, near the kerosene lamp, otherwise it would be too dark for us to see what we were doing.”

Learning on the job

Each morning, Lai’s mum would deliver their collective efforts to the Kwong Hing Tai factory by foot. She’d exchange two baskets of braided firecrackers for two baskets of unbraided firecrackers (with more than 8,000 individual firecrackers in each) to take home.

The family regularly stayed up past midnight to complete their task, and Lai barely remembers doing any homework.“We often got sleepy, our mother would scold us, we’d cry, but we still had to carry on braiding because we relied on it to eat, to sustain our living,” Lai says.

Making firecrackers was risky work. While the most dangerous parts – like inserting gunpowder – took place inside the factories, “safer” jobs like braiding could still go horribly wrong. The firecrackers Lai’s family worked with entered their home with their fuses attached; these could accidentally ignite and cause serious burns.

Lai admits there were dark times in his childhood. His mum was under immense pressure to provide for her family, and she could be harsh. But Lai chooses to focus on the wisdom she imparted.

“My mother used to tell us, ‘Help people whenever and wherever you can,’” he remembers. “She also emphasised the phrase, ‘力賤得人敬,口賤得人憎’ (meaning, ‘Speak with your actions, not with your words’).”

Lio Man Cheong, one of Macao’s most prestigious painters, also worked for a firecracker factory as a child. His memories are similar to Lai’s, though his job – rolling cardboard firecracker tubes – was considered safer.

“Most children would quickly finish off their homework then take part in the labour to help support the family,” says the 71-year-old artist. “But the incomes [from firecracker making] were not high, often only enough to cover the electricity and water bills.”

A firecracker industry in decline

Macao’s firework industry started to falter in the 1960s. Lai suggests that people started to realise just how perilous it was to make and use these explosive products.

“In Macao, Hong Kong and across the world, a lot of fires and accidents were caused by firecrackers, so they were restricted in many countries,” he says. “Sales began to drop.”

Lai recalls a conversation he had with Kwong Hing Tai’s former factory manager, about how firecrackers made in Macao were more faulty than those made in the mainland.

“[The manager] told me the ratio of functional firecrackers was around 80 per cent good to 20 per cent bad here, compared to 90 per cent good for firecrackers manufactured in the mainland,” Lai says.

Other industries were also on the rise in the city, offering safer employment opportunities.

Lio, meanwhile, views the decline as an inevitable consequence of social and economic progress. “As our society evolves, some things are just bound to be eliminated. We can do nothing about that,” he says. “The firecracker factories just remain a part of our memory – a city memory.”

Recording Macao’s firecracker days

While the firecracker era was fraught with toil and danger, Lai and Lio both found themselves working to preserve that chapter of Macao’s collective memory later in life.

Four of Lai’s seven published books focus on the industry. When he was researching his first book, Reminiscence of Old Taipa (《氹仔情懷》), which was published in 2010, he realised that nearly everyone he interviewed had worked for a firecracker factory at some point in their lives.

For his next book, Lai wants to document the factory that dominated his childhood: Kwong Hing Tai, the largest in Taipa. “It is worth mentioning Kwong Hing Tai’s owner, Chan Lan Fong,” says Lai.

“If in my remaining lifetime I am able to complete the book, Kwong Hing Tai’s ‘King of Firecrackers’ – Chan Lan Fong, that would be great.”

Lai, who conducts all the research for his books himself, admits that time is against him as he approaches his mid-70s. But he is determined: “People of our generation have a deep connection to Taipa, so no matter what, I will give it my all to accomplish what I want to do,” he says.

Lio, meanwhile, held an art exhibition titled, “Macau’s Firecracker Industry – New Works by Lio Man Cheong” in 2018. His ink wash paintings depicted the various procedures involved in firecracker making.

“This industry has now disappeared, but it used to be one of Macao’s largest industries – so I think it is worth recording,” the artist says.

From art exhibitions to the new industrial tourism site, Lio sees heritage preservation as an important educational tool – a way to teach younger generations about the historically significant firecracker industry and its role in shaping modern Macao.