Poet and artist JinJin Xu, a 2023 honouree of Forbes China’s 100 Most Influential Chinese, meets me at a local cafe in Taipa. She may be leaving at the end of this month, but nothing is set in stone. Xu has recently returned to Macao from New York for After Oriental Garden, one of Art Macao’s ongoing local curatorial projects at Casa Garden. Two installation art pieces that Xu made while in Macao are currently on display.

Xu’s ethereal fog installation, You Still Have Something of The Ghost About You, presents various interpretations of the afterlife. Meanwhile, her fly-trap-inspired installation, What Would You Say if You Could explores the thoughts, feelings and experiences of marginalised women around the world.

[See more: After Oriental Garden: Exploring colonialism’s marginalised voices]

Xu’s art often explores liminal spaces and dislocation, which reflects her experiences as a bilingual person who has lived amongst different cultures. New York, Shanghai and Macao each have a distinct impact on her identity, which manifests through her art in interesting ways. “I have different limitations and constraints in each space that is also reflected in the medium and the language I use,” says Xu.

Xu describes herself as living in between Macao and Shanghai while growing up because of her parents’ jobs, although she was born and raised in the latter city. Significantly, Xu doesn’t feel like she fully belongs in either.

When Xu is in Shanghai, she finds that the “boundaries” of her identity begin to blur and that she feels “less comfortable writing about family or more personal things when I’m close to them.” In Macao, Xu doesn’t fully feel like herself either, because she doesn’t speak Cantonese. She observes that she finds herself gravitating more towards abstract and performative mediums like film, performance, sculpture or installations whenever she is on our side of the world.

[See more: Art Macao 2025 kicks off with city-wide exhibitions]

New York is where Xu feels the strongest sense of belonging. “It’s a place where I made a home for myself as an adult. I chose it.” She feels less bound by expectations surrounding her identity and feels liberated by the city’s multiculturalism. The Big Apple is where Xu expresses herself more directly through the language of poetry. However, even Xu’s poetry inevitably possesses liminality. “I’m always translating in some ways,” she explains, whether it be from Chinese to English or vice versa. “I always feel like I’m writing in a secret language.”

The defining period in her life that molded Xu fundamentally and deeply influences her art to this day was when she was awarded the Thomas J. Watson Fellowship in 2017/8 as a graduating senior at Amherst College, where she studied BA English Literature. The fellowship gave Xu the freedom and funding to explore the world for a year. According to the fellowship’s official description it gives recipients full reign on “where to go, who to meet and when to change course” away from the US and their home.

“I proposed going to parts of Europe where there are refugee camps, and then different migration routes in Southeast Asia and Africa, and that’s basically what I did.” During that time news about refugees was prolific, sparking up lots of conversation and contention across the world but especially in Europe. Xu had a deep desire to understand the experiences of refugees, migrant workers and those dislocated by choice or circumstance.

[See more: Meet Diwa’s Lam Wai Hong, who is nurturing the electronic music scene in Macao]

Xu travelled across nine countries, beginning in Berlin, Germany and finding her way to places like Syria,Turkey, Vietnam and Thailand. The process was organic – she would meet refugee women, migrant workers or artists and she would travel to places that they had passed through to get here, or places that they suggested she go to. Some were fleeing from war, some were victims from human trafficking, and some were dislocated by choice. With their consent, she began to create voice recordings of their stories.

“I didn’t know why I was recording. I just wanted their voices to be heard. I also wanted to honour the fact that when you record someone’s voice, there’s this implicit promise that they will be heard in some ways.”

During that time Xu began questioning her own privilege and the purpose of making art, and considered becoming a journalist or a documentary filmmaker. “Why am I doing this in these privileged settings, and what does it mean for me to keep making art? To call myself a poet, call myself an artist, like it just felt really painless and really detached from everyday life.”

[See more: ‘Enjoy being yourself.’ Meet Jay Sun, founder of the Macao International Queer Film Festival]

Xu held onto those recordings for two years, not certain of how to honour them. Around 2021, she discovered the near extinct Chinese writing form nüshu (女書), which translates to “women’s script.” Characterised by its spidery and elegant characters, nüshu is a secret written language passed for centuries from mothers-to-daughters who had no access to education in Jiangyong, a county within the Chinese province of Hunan. It was an outlet for women at the time to express their thoughts and emotions to each other away from men.

“I realised that this is the language I’ve been looking for, this secret women’s language that almost has power in its illegibility.” Xu travelled to the village in Hunan, near where her mother grew up, and befriended the last natural heir of the language He Jinghua (who Xu refers to as “Grandma He”). Xu told them about her recordings, and He wrote them out for her in nüshu.

“It finally felt right to turn [the recordings] into something untranslatable, or translate it into something untranslatable in some ways.”

[See more: Ioi Choi: When bodies paint stories]

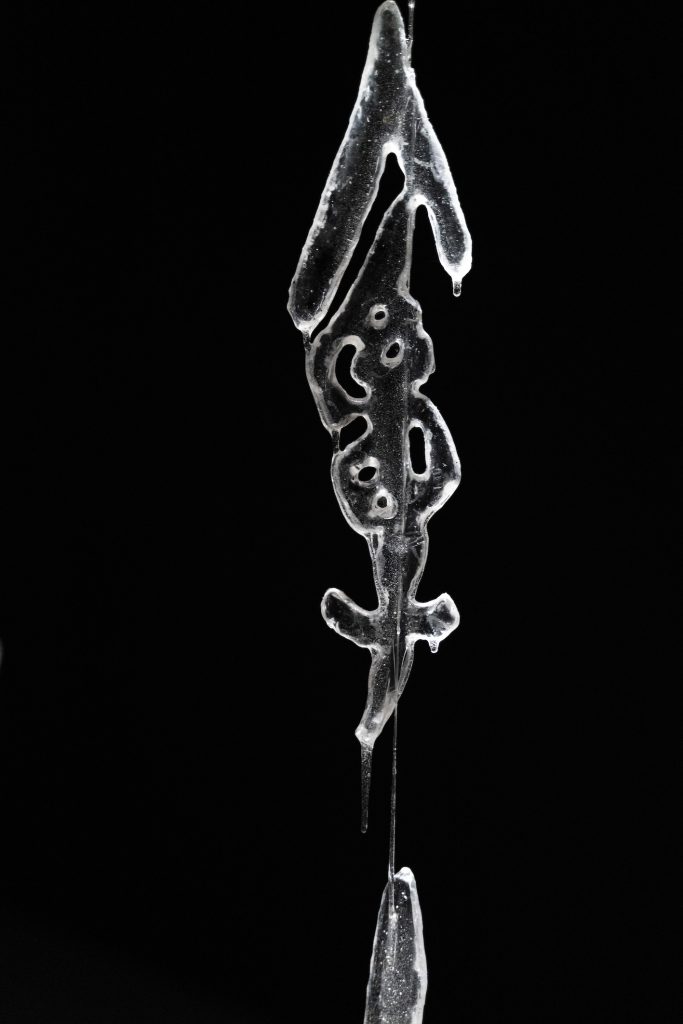

Nüshu, and what Xu describes as “docu-poems”, has since become a defining element of her work. In Xu’s 2024 Against This Earth, We Knock installation at Shanghai’s How Art Museum, Xu created chains of nüshu text using resin, suspending them from the ceiling into pots and ashes collected in Jiangyong. Each chain of text is the secret of an anonymous woman, sculpted in collaboration with Grandma He and Hu Xin, the youngest ambassador of the form.

Earlier this year in May, Xu had her first solo exhibition in Macao What Would You Say If You Could? at Butter Room. For three weeks, she froze seawater and carved nüshu into the ice before it melted. Her fly-trap inspired installation, which is currently on display at Casa Garden, is a poignant metaphor for how home and danger are not always mutually exclusive. Both feature the docu-poems of displaced women which viewers can listen to as they move through the exhibition space.

As our conversation draws to a close, Xu leaves us with questions that have been on her mind. “What is our responsibility towards these hauntings that are passed on to us? What does it mean for us to forget, to remember?”