The Macao government wants non-gaming activities to make up 60 percent of GDP by 2028, with the remainder to be provided by gaming tax revenue. When you consider that non-gaming activities provided just 16 percent of GDP in pre-pandemic 2019, the scale of the ambition becomes clear.

To help achieve the goal, the authorities have required gaming companies to collectively spend 130 billion patacas (US$16.1 billion) outside the gambling halls over the next ten years. The concessionaires have obliged: this year alone, they have announced urban regeneration projects and plans for major sports events and public leisure facilities.

But snooker tournaments and neighbourhood revitalisation aren’t, by themselves, going to transform Macao’s economy to the extent that the government requires. The anticipated growth in gaming will also make it harder to reach the 60 percent non-gaming target. So we need to think laterally. Specifically, we need to be thinking of hotel rooms: the concessionaires should be allowed to build thousands of additional hotel rooms and to consider those rooms as part of their investment in non-gaming infrastructure in Macao.

[See more: How would you spend a trillion patacas? (That’s US$124 billion)]

Why hotel rooms, as opposed to more sports events or museums?

Most tourist activities, shopping, gambling, dining, or seeing a show, compete with each other for tourists’ time and money. When visitors are sightseeing – or waiting in a long taxi queue – they are not spending money in restaurants or boutiques. But hotel rooms give visitors more time to do all of the above. It’s obvious that the longer visitors are here, the more the local economy benefits, and everyone wins.

Unfortunately, Macao is desperately short of rooms. The city has 46,000 rooms at present, compared to 153,000 in Las Vegas. In pre-pandemic 2019, a total of 42.5 million people visited Las Vegas, staying an average of 3.4 nights and 4.4 days and pumping huge amounts of money into local businesses. Between them, they accounted for a total of 48.3 million hotel room nights sold. In the same year, just 18.6 million of Macao’s total 39.4 million visitors stayed overnight. Evidently, many of them chose to stay up all night, or on a friend’s sofa, since only 14.1 million guests were recorded at hotels and guesthouses for 2019.

As transport links improve – Macao is hoping to establish a link to the national high-speed rail network, for instance – the number of same-day visitors can even be expected to increase. Not all can be persuaded to stay in Macao just because more hotel rooms are available. But Macao doesn’t need to persuade all of them. Just a few.

The 20.8 million same-day visitors in 2019 spent a collective 14.12 billion patacas, or 680 patacas each. Overnight visitors spent 50 billion patacas in total or 2,681 patacas each. In other words, if we use 2019 figures, Macao would only need to persuade an additional 5.27 million visitors to spend the night to match the entire economic contribution of all same-day visitors. The job will be easier to do than at present, because as more rooms become available, average rates come down.

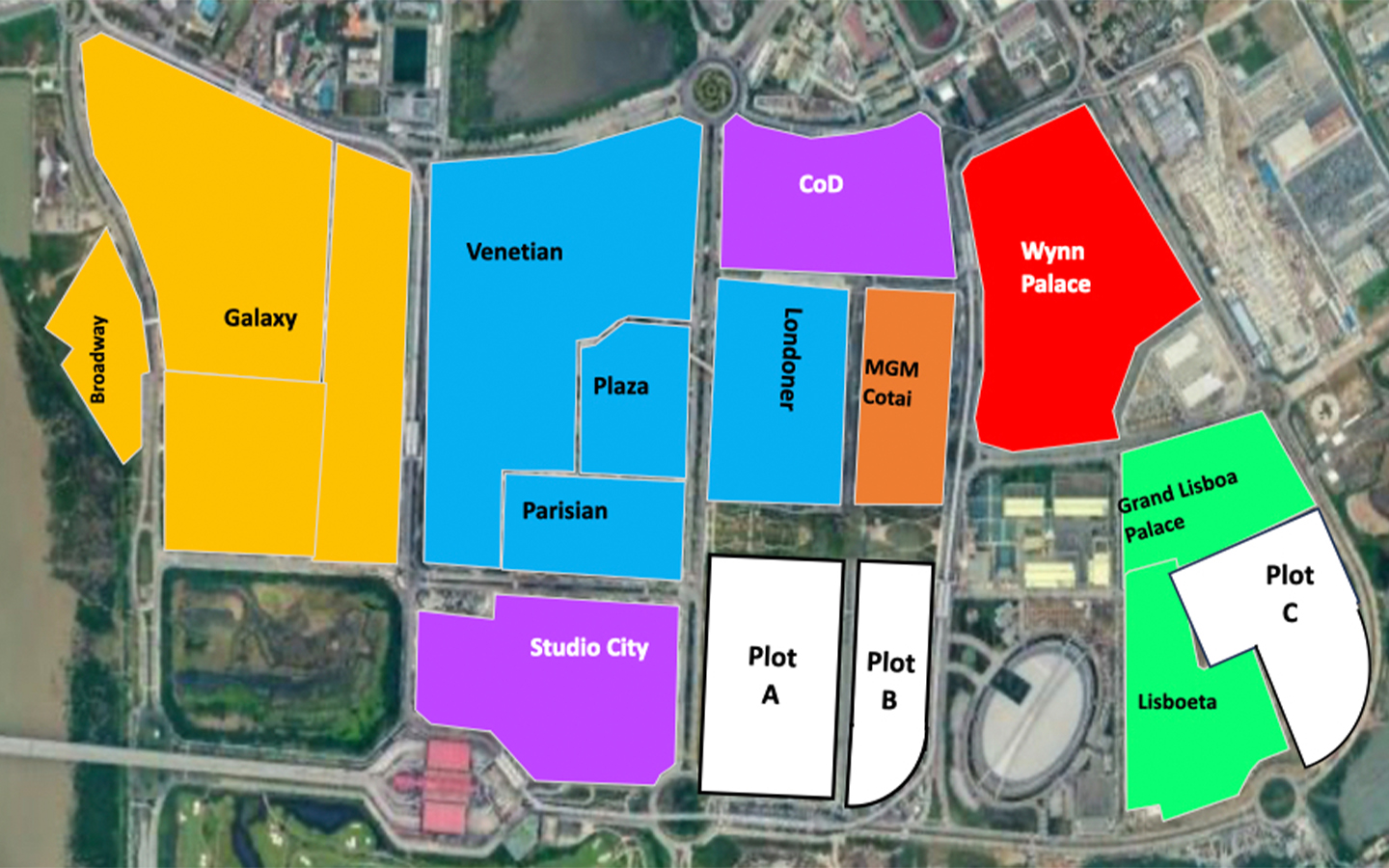

How many additional rooms does it take to house the 5.27 million? At two people per room, just over 7,200 hotel rooms, assuming they are occupied every night of the year. And that’s great news for Macao, where land is precious. The large plots of land (Zone A, B and C) currently vacant in Cotai could comfortably accommodate twice that number of rooms, if the infrastructure was designed properly. The Londoner Macao has managed to pack 6,000 hotel rooms into roughly the same area as Zone A.

The government could entice generous bids for the land from casino operators if it set a room-to-gaming-unit ratio – permitting, say, one table and three slot machines for each 20 rooms built. That would lead to a 300-table, 900-slot-machine casino for a 6,000-room hotel. The Macao government could further stipulate that no more than 40 percent of those rooms be “comped” (made available gratis) to gamblers, leaving the rest to non-gaming visitors, who tend to spend much more money shopping, sightseeing and dining.

[See more: Macao can forget about being an international destination until it fixes its taxi problem]

Other advantages would follow. Macao would attract a broader range of travellers – such as convention delegates and families – each contributing to a less gaming-dependent Macao.

Thousands of non-gaming jobs would be created in hotels, hospitality, transport, entertainment and so on, improving the local standard of living.

In fact, the 60 percent non-gaming target that the Macao government is aiming for in 2028 matches what Las Vegas has been averaging over the last several years. The sometime “Sin City” made the transition from a gaming destination to a family-friendly entertainment hub precisely by building tens of thousands of hotel rooms.

If Vegas can do it, so can we.