Because of the Covid-19 pandemic, 2020 was the worst year in decades for casinos around the world. But unlike operators in most other jurisdictions, which had the power to layoff their employees and ended up doing so, Macao’s integrated resorts didn’t touch their local hires, who comprise the vast majority of their headcount. They strongly believed they would lose any chance of renewing their expiring gaming licences, if they were to do so. According to persons familiar with the matter, casinos instead ended up laying off more foreign employees than they would have wanted to, in order to lessen their financial burden.

Gaming revenues for the year fell 79 percent over the prior year, and the six gaming companies lost a collective 11 billion patacas (US$1.36 billion) in earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation, and amortisation (EBITDA). In this horrendous climate, locals not only kept their jobs: the gaming companies ended up paying them annual bonuses. Clearly, operators saw the chance of another 10-year gaming licence as worth the additional expense.

The following year brought some hope, vaccines became available in 2021 and visitors from mainland China kept coming since they did not have to quarantine when entering Macao. This was in contrast to people arriving from foreign countries – including Macao residents – who had to endure a 14- or 21-day quarantine. Gaming revenues showed a modest uptick, climbing to 30 percent of 2019 levels – nine percentage points higher than 2020.

That early recovery was not to continue. Borders were being opened everywhere else, but China’s strict zero-Covid policy saw visitor numbers reduced to such an extent that each of the last 10 months of 2022 generated less gaming revenue than any of the 17 prior months from October 2020 to February 2022. Gaming revenues stood at 14 percent of what they were in 2019 and gaming operators lost a combined 10.3 billion patacas (US$1.28 billion) over the last nine months of the year.

In spite of this, the government went on with the process of selecting candidates for the next batch of 10-year gaming licences, given that current licences were set to expire at the end of 2022. The six original operators, plus Genting, a new entrant, submitted their documents in September.

The Macao government insisted on duplicate submissions on paper, in spite of the fact that documents totaling tens of thousands of pages were required of each operator.

[See more: This is how much gross gaming revenue Macao generated in October]

The sheer volume of the submissions was overwhelming. One company’s submission was the size of two refrigerators, side by side, each beautifully wrapped with a golden bow. Another company’s document bundles were so voluminous that they wouldn’t fit through the gaming regulator’s doors. The government took the documents and said it would announce its decision in a few weeks.

The gaming operators kept their chequebooks open in the meantime. In November, they shelled out 28.5 million patacas (US$3.5 million) in sponsorship money for the 2022 Macau Grand Prix, which featured few international drivers because of pandemic-related travel restrictions.

The government’s masterstroke

Macao’s casino operators have long lobbied for tax breaks. Gaming taxes in the territory were 39 percent – almost six times higher than the 6.75 percent levied in Las Vegas.

The Macao government’s response has always been that while gaming taxes are higher, so are operators’ profits. In 2019 alone, the six gaming companies combined to generate 5.5 times more gaming revenue than the Las Vegas Strip, and 79 billion patacas (US$9.8 billion) in profit, several times higher than other jurisdictions. To be sure, the pandemic resulted in huge losses but the government argued that the casinos should be able to match if not exceed pre-pandemic profit levels over the next 10 years.

[See more: Sands China’s CEO is optimistic about Macao’s economic future]

The government had its grievances too. It had long asked for more non-gaming investment, more transparency, and less reliance on junkets from the gaming companies, but its pleas were ignored. Now, it was able to use the licence renewal process to extract some concessions.

In late November 2022, the government announced its decision. In a much talked about photo, representatives of the six gaming operators were pictured on chairs, with their hands on their laps. Happily, the six were awarded new 10-year gaming licences, which started in 2023 and expired at the end of 2032. Newcomer Genting’s bid had not succeeded, but that was not a surprise. After all, the existing players had spent billions building world-class integrated resorts.

The agreements were signed three weeks later and the government, sensing it had the upper hand, used them to formalise unprecedented power over gaming operators.

Gaming taxes were increased to 40 percent. The period of the gaming licences was reduced from twenty years to ten, with assessments to be held every three years. Macao’s chief executive was given the power to revoke a licence in the event of a threat to national security. Operators had to seek approval before expanding to new jurisdictions or issuing dividends to their shareholders.

The authorities were empowered to set minimum annual revenues for what are known in the business as “gaming units” – that is, tables and slot machines – and impose related fees. They could also take gaming units away.

[See more: Earnings from gaming tax have increased by more than 200 percent year-on-year]

Most remarkably, the gaming companies were now required to spend on non-gaming facilities and infrastructure – from outdoor recreation areas to cultural venues and sporting events. The amount for each operator was determined by an opaque formula but collectively the six concessionaires pledged to spend – at least – a staggering 108.7 billion patacas (US$13.5 billion) over the course of their licences.

It was a sum far above what anyone expected. The government had been asking for non-gaming investment for years, with little effect. Tying the demand to the renewal of gaming licences was a masterstroke.

But that’s not all. There was a stipulation that if Macao’s total annual gaming revenues reached 180 billion just once in the first five years, the non-gaming spending by each operator would have to increase by another 20 percent, thus reaching a combined 130 billion patacas (US$16.2 billion).

There is every chance of this threshold being reached – as it was consecutively from 2010 to 2019. With under two months remaining in 2023, Macao is on pace to reach the 180 billion mark (US$22.3 billion) this year. But even if revenues end up falling short this year, the government’s own expectation for 2024 is 216 billion patacas (US$26.8 billion), 20 percent higher than the threshold.

Carrot and stick

In the meantime, the government made dramatic adjustments to the number of gaming units each concessionaire was allowed to operate, directly impacting bottom lines.

MGM was the major winner, receiving 200 more gaming tables than it had under its previous entitlement, taking its total tables from 550 to 750 – a jump of 36 percent. Sands was allowed to keep its 1,680 tables. Galaxy lost 7 percent of its tables, but that was due to the closure of two satellite casinos.

Wynn saw its tables decline from 670 to 570, meaning that it went from having 120 more tables than MGM previously to having 180 fewer now – a big disadvantage. Melco lost 200 of its 950 tables. Its 400-table lead over MGM before this year vanished, leaving it with merely the same number of tables as its rival.

SJM, the late Stanley Ho’s casino empire, lost 750 tables, 38 percent of its inventory, taking its total from a leading 2,000 tables to 1,250. This was in part due to the permanent closure of 10 satellite casinos.

All these changes were made using an opaque process. A transparent “pay to play” system would prove beneficial to all parties, however. Imagine how much more the operators would commit if the price of an extra gaming table was set to say, a million patacas in additional non-gaming spend. The same exchange rate could be used to punish operators should they fail to meet their present commitments.

A lot of zeros

The 130 billion patacas (US$16.1 billion) in promised non-gaming spending over the coming decade is a bonanza for the Macao government – a sum that any municipal authority anywhere in the world would salivate over. It is four times the entire annual operating budget of Boston, the entire budget deficit of Kuwait, or equivalent to the total cash handouts that Thailand will soon dole out to 55 million adults in a bid to kickstart its economy.

However, the sum is a small change compared to what Macao stands to levy in gaming taxes over the course of the new concessionaire licences.

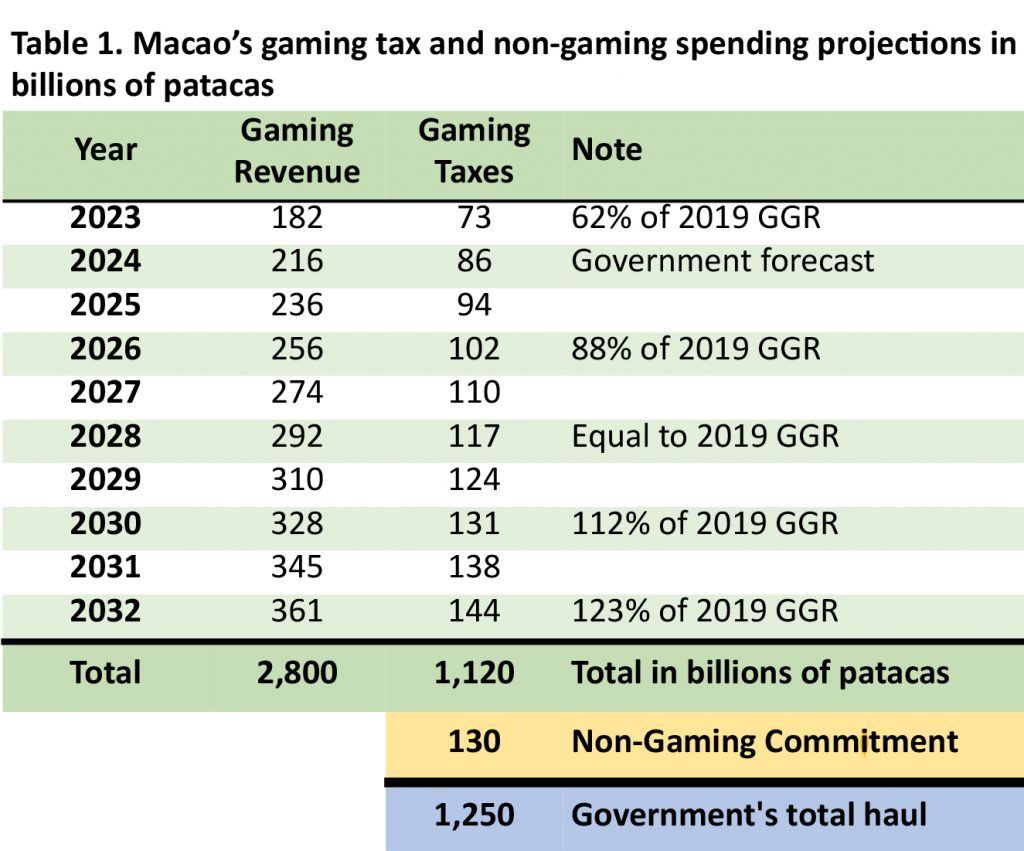

The table below is based on conservative projections of Macao’s gross gaming revenues (GGR) over the next decade. It assumes, for instance, that pre-pandemic GGR is not matched until 2028. It also estimates that the all-time high of 361 billion patacas (US$44.8 billion) reached in 2013 will not be equaled until 2032.

In other words, the government will make a massive sum from concessionaires in the next 10 years: 1,120 billion patacas (US$139 billion) in gaming taxes which is not often talked about, plus the much talked about 130 billion patacas in non-gaming spending commitment, for a combined total of 1.250 trillion patacas (US$152 billion).

Let’s put that in numbers: 1,250,000,000,000. That’s 1.83 million patacas for every person in Macao. It’s more than the amount spent on 1,800 projects under China’s signature Belt and Road Initiative. It’s bigger than the size of the entire global food delivery market.

[See more: Macau Legend is pulling out of gaming projects in offshore markets]

As a statistician, I’m used to dealing with large numbers – especially when working in the gaming industry. In Vegas, millions were usually the largest units when it came to describing monthly revenues or visitors. When I came to Macao in 2006, using billions became commonplace, for talking about rolling volumes in VIP gaming, or monthly casino revenues. But the coming years will take it to another level, as I find myself working in trillions for the first time in my career.

The questions are: What are we going to do with all this money? Who gets to decide?

‘Shocked, shocked’

Right now, there is no central committee to coordinate how such fantastical sums can best be spent, and one is urgently needed. It should comprise officials, legislators, academics, gaming industry representatives, NGOs, and others. Its deliberations and recommendations should be transparent and it should be open to receiving pitches from residents and any organisation with a stake in Macao.

The committee should work to avoid duplication: Macao does not need six film festivals or six hospitals or six arenas. Above all, the committee must try and get the biggest bang for the buck. Is spending 20 million patacas (US$2.5 million) on a sporting tournament or art gallery really the same as spending 20 million patacas on a healthcare facility?

The government’s stance towards gaming operators has been hardening despite the latter bending over backwards to meet the former’s demands.

Listening to official rhetoric over the last few years, I’m constantly being reminded of Captain Renault’s infamous line in Casablanca: “I am shocked – shocked! – to find out that gambling is going on in here!” The remark is immediately followed by a clerk handing him a sheaf of banknotes, while telling him “Your winnings, sir.”

As Macao economist Jose Duarte said in a 2022 panel discussion, “Gaming is like a very rich uncle that nobody loves too much, but everybody loves the money he brings. Gaming is blamed for several ills, but at the same time, it’s the source that will allow us to solve those ills.”

It’s time for us to figure out how the government, aided by gaming companies, is going to do that.

Alidad Tash is the managing director of 2nt8 Limited, a consultancy specialising in international casinos and integrated resorts. This is the first in a series of articles that will offer suggestions on how Macao can best spend its expected gaming revenues.

The views and opinions expressed on this piece are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of Macao News.