Over the past 12 years, Max Bessmertny has directed, written and produced short films, documentaries and commercials in Asia and Portugal.

In 2014, the Macao-raised filmmaker’s short film “Tricycle Thief”, in which a tricycle driver goes on a money hunt after being evicted, became the first locally made movie to premiere at the Toronto International Film Festival.

More recently, his works, “Dirty Laundry” (a comedy about two friends getting rid of a broken washing machine) featured at the International Film Festival and Awards Macau in 2019 while “The Handover”, about a couple who struggle to get their affairs in order as they move out of their apartment, was the fruit of winning a bid to produce a short for the Macao Cultural Centre’s “Local Viewpower” competition to celebrate the 20th anniversary of the city’s transfer of administration from the Portuguese to Chinese in 2020.

Bessmertny’s films, so far, have been witty snapshots of the Macao life. His characters tend to be in transitional periods of their lives (usually in the middle of moving out) tasked with getting a mission or a chore completed and centres around the trials and tribulations of achieving that goal.

Given his track record, it’s safe to say that Bessmertny knows a thing or two about directing and producing short films. But for the first time, he has embarked on a feature-length movie called “The Violin Case”, which follows an artist after he loses a painting in the back of a taxi in Macao. Taking place over the course of one night, the movie revolves around the artist’s odyssey-esque search for the missing piece and all the people he encounters along the way.

Production for the movie is set to begin in August and, in the meantime, Bessmertny has launched a crowdfunding campaign to help raise funds. We caught up with the 33-year-old film director to learn more about his career and vision for the upcoming comedy:

Macao News: How did your interest in filmmaking begin?

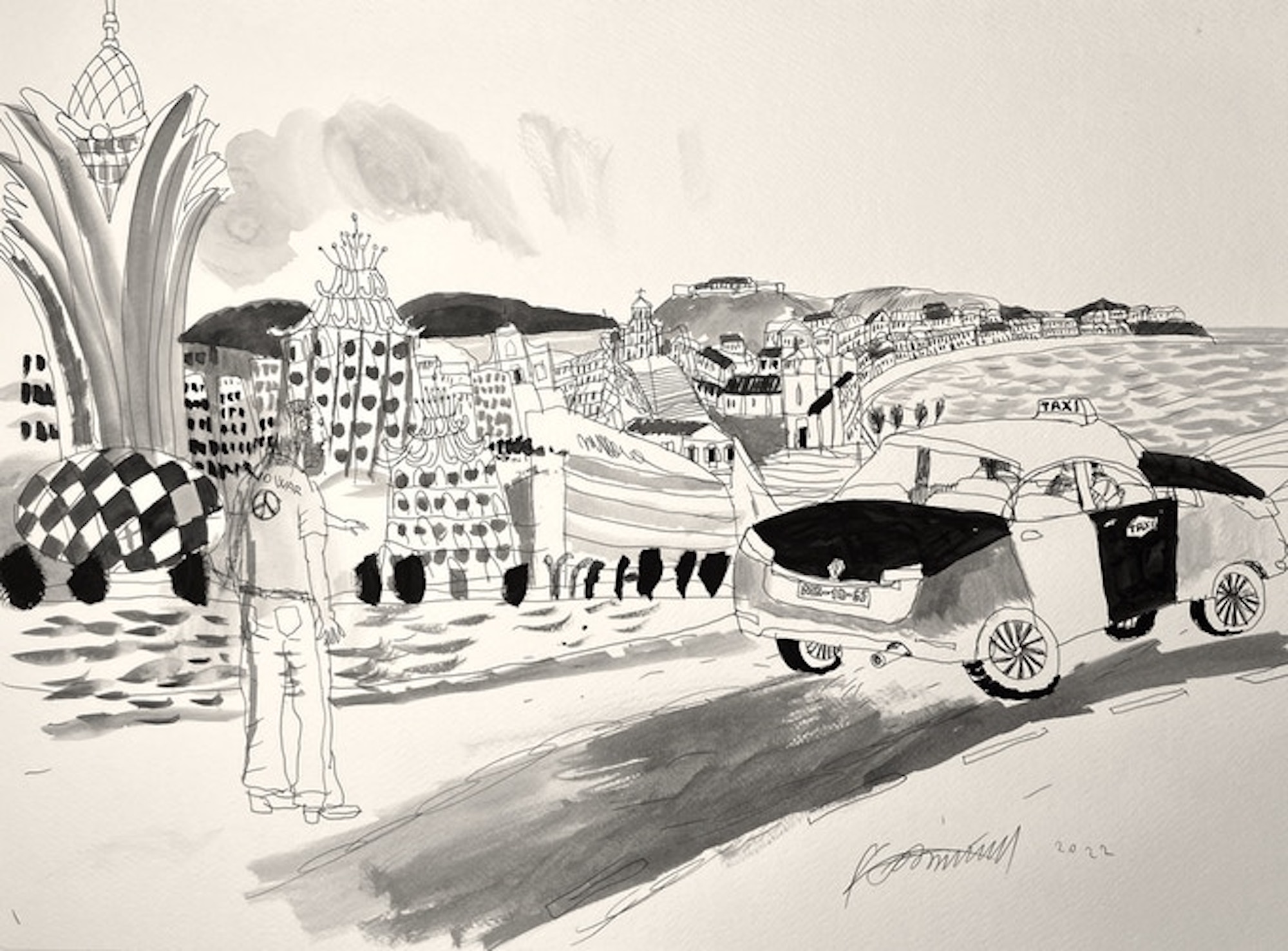

Max Bessmertny: It started a long time ago, because my dad (renowned artist Konstantin Bessmertny) used to walk around with a video camera all the time during our holidays. But I slowly got excited by watching different films, as well as watching stuff that my dad would show me. He introduced me a little bit to more old-school cinema, as well as the work of [Japanese filmmaker] Akira Kurosawa and, from there, I watched David Fincher’s films, like ‘Seven’.

My friends and I also made our own videos. I mean, we were pranksters back in the day before YouTube existed. We were always skateboarding and I would take my friend’s video camera and hold it while he was doing all these tricks over a ramp in Hong Kong or somewhere in Macao. So that was just a fun thing. I didn’t know that later on, I would be able to make a living out of it.

MN: What is your favourite movie genre?

MB: As a viewer, I love crime dramas.

MN: What about as a creator?

MB: I’ll have to go for comedy, because I like funny situations, and also crime with some drama.

MN: Name some filmmakers who have inspired you.

MB: Orson Welles, Wes Anderson, Federico Fellini and Quentin Tarantino.

MN: What are some movies that were critical to your development as a director?

MB: ‘Seven’ by David Fincher; Citizen Kane, [Orson Welles]; ‘Seven Samurai’ by Akira Kurosawa, and another one that was terrific that just came to my mind is ‘Dog Day Afternoon’.

MN: How would you describe your movies?

MB: Eccentric, fun and witty.

MN: What is it like working in the film industry?

MB: It’s bloody tough. I think it’s really, really tough and it’s tough anywhere in the world. It’s easy to dream, but hard to put things into reality. So that’s the challenge. You can call what we do creating art but, at the end of the day, a movie’s a movie so people hopefully go to the cinemas to see it and they buy tickets for it or watch it on a streaming service. We’re trying to make a movie and that’s still an entrepreneurial venture, you have to figure things out. It is constant problem-solving.

MN: Most memorable experience in your film career so far?

MB: I attended the Toronto International Film Festival in 2014, and it was amazing. I was there to show my short film ‘Tricycle Thief’. Showing the movie there and getting people’s reactions and hearing them tell me about their own experiences in Macao in the ‘80s was very memorable. I was also amazed by Canadian culture – Canadians are really funny and sarcastic.

MN: Do your movies share any common themes?

MB: I like each story to be a little bit different, but we all have our own prerogatives. We kind of tend to jump back to them and go back to what really bothers us. For me, the theme of identity is a big one: because who are we? Who am I? What am I doing here? I ask myself these bigger questions and it ends up coming out in a lot of my films.

My movies are also about people coming together to try to achieve something. So this kind of theme runs through a lot of my work. There’s somebody with a dream – there’s somebody who wants something, like a rickshaw driver who wants to pay off his rent, but there’s a way that he does it. And so, for me, that was layered in identity, being in Macao and observing different characters as well. Another theme that comes across a lot of my films is self-reflection. I guess ‘obsession’ is another word for it.

MN: How would you describe your filmmaking style?

MB: I guess that’s a question for the audience or for a film critic. But because I have been making most of my films in Macao, my style is very cinéma vérité – very documentary-like – so very on the spot but in a way that’s planned. I try to make immersive films. At least my last two were more immersive.

MN: What are some of your favourite places to shoot in Macao?

MB: I like shooting in the Inner Harbour. I love that area – the length of it from Sai Van all the way down to Red Market. It fascinates me because of the fishing and port industry. We’re a small city, so if we need food, it comes from outside. So anything that comes in, is coming in from that area. That’s kind of inspiring, because you’re like, ‘Okay, so what if we didn’t have that?’ I’d be really scared. So anything that scares me is kind of a cool place to film it right? You get to be out of your comfort zone when you’re filming.

MN: Are you inspired by Macao at all when making your movies?

MB: I’m from Macao and I grew up here, so you write what you know and what you see. I love this place and have a lot of passion for it. This is my home, so I’m inspired by everyday life here.

MN: What facets of Macao life do you draw from?

MB: People here come from many different places, so the multicultural aspect is a massive one. If you live in a certain area in Macao, you’re almost in a whole other universe. Like there’s so many tiny little universes here and that’s the beauty of it – everything is on display. You really learn about life very intensely, living in a place like this. We see it from every angle, from every industry, whether it’s markets or dai pai dongs.

You go out to eat dim sum for lunch and you have new story inspiration or you’re walking through a tiny little street in Fai Chi Kei or Iao Hon or the market there. It’s not just beauty, either, but conflict and contrast as well. For example, the huge wealth gap is a big problem here and people have different dreams. So everyone has their own ambitions and projects. It’s really difficult to capture all this in one story but it can be done.

MN: What do you think about the local film industry?

MB: I’ve been making films for 12 years, and it’s changed a lot. Any industry is as good as its people, and we have great people in this industry. The more things we do, the more projects we create, the more opportunities we create. And the more other industry sectors see that we’re trying to do things, the better it is for us.

We want to grow, of course, and I want this to be an industry that’s taken seriously. That’s not just up to us but also to the public sector. We want them to see that this is something that’s worth developing.

MN: Your upcoming feature film was inspired by a real event, tell us about that.

MB: The plot was inspired by something that happened to my dad, who is an artist, six years ago. He left a painting in the back of a cab in Hong Kong. He went to the police station and went through CCTV footage but never found the painting. It was difficult, because he was actually on the way to a client who wanted to buy it.

It was obviously disappointing and shocking but the artist has to move on. For me, that kind of incident really made me use my imagination. I remembered it during the start of the pandemic in 2020 and I knew I would write a movie around it.

MN: The movie is being produced, in part, with the help of crowdfunding. Did you always plan to involve the community?

MB: When you’re making a film, you’re firing on all cylinders. As soon as you decide to make a movie, it’s up to you to get it made. It’s been especially hard during the pandemic. The first thing to get cut in the pandemic is the arts, which is unfortunate because it is the glue that holds society together. We tried funding through different subsidies from all over the world – trying to see if there are any project markets interested.

But for a project to take off, it requires real backing. I’ve been developing this feature film for 2 and a half years. Somehow, rejection has been a great motivator for me, it just meant that I hadn’t found the right strategy for these times. Once the strategy became clear for this story, we decided to move forward and fast.

MN: How did this impact your decision to crowdfund the project?

MB: Making independent films is an incredibly challenging venture. Kickstarter is a way to involve the global community of art and film lovers and supporters in the project. It is an all-or-nothing scenario. We set our target at US$ 50,000 and unless we achieve it or go past the target, the backing is returned. Naturally, the amount we are raising on Kickstarter is an important addition to the minimum that has been raised so far through the local community, which gave the film a starting point. A successful Kickstarter with global support will bring us closer to the finish line.

“The Violin Case” is a community-funded and driven film with a terrific team all based in Macao, it creates an additional snowball effect. Casting sessions are also coming up in the next two weekends and we have so many different roles and parts, all spoken in a variety of languages that you see being used here on a daily basis.

It’s been an unbelievable experience but also inspiring. When people and the community get together? It’s really, really fun.

MN: What advice do you have for budding filmmakers?

MB: Make sure you have a Plan B! This business is really, really hard but don’t give up! Keep going! If you have an idea, find a way to make it happen.

Visit the crowdfunding page for ‘The Violin Case’, which was highlighted by Kickstarter as a #ProjectWeLove, to learn more about the movie and how you can support this creative pursuit.

This interview has been edited for clarity and brevity.