On 3 September, China will be hosting a military parade to mark the 80th anniversary since the end of the Second World War (1939-1945). While the prevailing narrative sets Germany’s invasion of Poland in 1939 as the starting point of this conflict, the Asian theatre of the war can be traced as far back as 1931 to Japan’s gradual encroachment into Chinese territory, which culminated in the Second Sino-Japanese War (1937-1945).

Known in mainland China as the War of Resistance against Japanese Aggression, this conflict was one of the major campaigns of World War II, resulting in the deaths of an estimated 20 million Chinese civilians and military personnel.

Major parts of China’s east and south were conquered by Japan during this period, including key cities such as Beijing, Shanghai, Xiamen, Guangzhou and Hong Kong.

Remarkably, Macao avoided falling into the hands of the Japanese due to a variety of factors, including the neutral status of the Portuguese government, which administered Macao at the time. However, far from being shielded from the impacts of World War II, Macao quickly became a dangerously overcrowded magnet for refugees hailing from all corners of the globe.

[See more: A snapshot into 1930s Macao: the photographic legacy of Melville Jacoby]

“Obviously a great majority were Chinese, but there were also people from literally all over – from South America and stateless Russians…to a range of other nationalities,” says Helena Lopes, a modern Asian History lecturer with Cardiff University who wrote the book, Neutrality and Collaboration in South China: Macau during the Second World War. “The whole world really was somehow in Macao during the war years.”

While there is no exact consensus on the number of people who fled to Macao, Lopes states that “there were at least half a million people living in Macao, 300,000 of whom were newcomers that arrived between ’37 and ’45.”

Geoffrey Gunn, an Emeritus Professor at Nagasaki University, who edited the book, Wartime Macau: Under the Japanese Shadow, agrees that “all statistics are rubbery,” as “no census [was] taken during this period.” He argues, however, that many scholars “concede at least a doubling of the population” to roughly 600,000.

Faced with an influx of refugees, the Portuguese authorities in Macao responded with a relatively open-minded policy. According to Lopes, “even though they [didn’t] necessarily want refugees,” the Portuguese accepted the realities of the situation, adopting a “slightly more flexible” attitude in comparison to other foreign concessions in Shanghai, Hong Kong and Guangzhou. In fact, Gunn says that Macao’s administrators began building barracks on Coloane as far back as the the period between 1937 and 1939 to deal with the initial wave of displaced people.

Was wartime Macao ‘paradise’ or hell?

Despite the seemingly humanitarian approach of the Macao’s government, the treatment of refugees differed substantially depending on factors such as one’s origin and wealth.

“People that came with their own means of subsistence and transfer of businesses and so forth were much more welcome than people who came destitute,” says Lopes. “Among people who came destitute, some were put into pretty bad refugee camps.”

The academic cites that Portuguese sources often used terms such as “beggar camps” or “asylums” to label these places whose situations were described as “horrendous.”

The radically different experiences of the different settlers is well-demonstrated by the testimonies of Stanley Ho, the Hong Kong businessman who made his name as Macao’s casino king in the post-war period, and Henrique de Senna Fernandes, the Macanese writer best known for composing The Bewitching Braid.

In the book, Macao Remembers, Ho describes Macao as “paradise during the war,” pointing out that he “had big parties almost every night” and that a person with the wealth could “enjoy the best cigarettes,” “carry on using motorcars and motorbikes” and “have excellent food” throughout the conflict.

By contrast, Senna Fernandes, who was also in a privileged position, albeit nowhere near the same level as Ho, recalls that “it was the worst kind of nightmare. I saw many, many beggars here who looked like skeletons…at the end of the war, they showed news footage of the horrible scenes at [the] Belsen and Auschwitz [Nazi concentration camps]. Those poor people, so thin and so maltreated. I wasn’t very surprised or horrified because I’d already seen it.”

[See more: Unveiling hidden histories: American traders’ glimpses into old Macao]

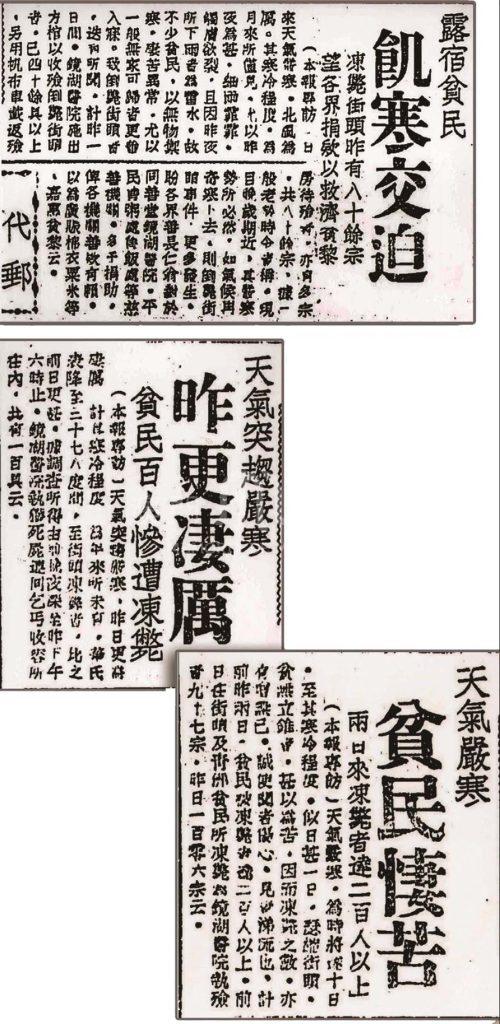

Indeed, Gunn describes Macao as “a graveyard for many of the refugee arrivals,” with around a thousand people dying in the city during the peak of the cholera epidemic between 1941 to 1942 and hundreds of fatalities each day when the food crisis reached its zenith during the spring of 1942.

Japan’s chokehold on Macao’s food supply and invasion of China’s urban centres played a role in these tragedies, which became so dire that there were occasional reports of cannibalism in the city.

Even the well-to-do residents in Macao were not completely immune to the adverse impact of the war towards its end, with Lopes stating that the food shortages began to affect government employees and other such people.

Still, as Ho and Senna Feranandes’ accounts illustrate, wartime Macao was a place defined by great ambiguity and wide contradictions.

“The fact that some people describe it in these very superlative, positive terms [such as paradise], and in others quite negative terms, also says something about how complex Macao was because it can actually be seen as both,” says Lopes.

Was Macao really neutral during the war?

Another contentious issue regarding wartime Macao is whether or not the territory was actually neutral. Depending on the historiography, the perspective can significantly differ. For instance, Lam Fat Iam, the head of Macao Polytechnic University’s Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences argued in a lecture earlier this year that the Chinese community in Macao supported the anti-Japanese war effort in various ways, even though the city was nominally on no side.

Certainly, there were local residents involved in the struggle against the Japanese, including educator, Liang Yanming, who was assassinated in 1942 by Chinese collaborators of Imperial Japan for supporting the Chinese resistance effort by means of disaster relief, fundraisers, donations and promotional events.

Another well-known figure is Liao Jintao, a covert Chinese Communist Party member, who rallied people in Guangzhou and other nearby cities in the war against Japan. Like Liang, Liao met a tragic end, dying in a jail cell at the tender age of 27 after being arrested by the Nationalist government.

[See more: Building a Macao icon: Lo Wing Cheung and the Hotel Lisboa]

On the flip side, there were also individuals who were willing to collaborate with the Japanese, including businessmen Dong Xiguang and Kou Ho Neng, who were labelled as “economic traitors” for conducting business with the enemy, with the mainland government seeking their extradition from Macao. In Kou’s case, there was an element of moral ambiguity, as he was greatly involved in charitable efforts during the war and had been recognised for his contribution by the Portuguese administrators.

The situation was equally murky within the Portuguese colonial government, with Gunn pointing out that it “was rent with factions.” The academic argues that while it is possible to portray Macao’s wartime governor, Gabriel Maurício Teixeira as a “centrist” or a loyal government figure, “certain key individuals went out of their way to coddle the Japanese.”

One example is the Macao police commander Carlos de Souza Gorgulho whom Gunn says “visited Tokyo during the war to receive a special honour [Order of the Rising Sun (fifth class)] for his services rendered in Macao to Japan.”

Why did Japan honour Macao’s neutrality?

As a neutral territory in wartime China, Macao was by no means unique, as other parts of the country, including Hong Kong, Shanghai’s foreign concessions and the French-controlled Guangzhouwan, also maintained a non-belligerent status during the initial stages of the Second Sino-Japanese War.

According to Lopes, what set the then-Portuguese enclave apart from these other foreign-controlled territories was that it was “never completely occupied” by the Japanese throughout the duration of the conflict.

A number of strategic reasons prompted the Japanese to respect Macao’s neutrality, with one of them being the demands of maintaining control of a territory.

“A formal occupation involves some resources that Japan doesn’t really have and that’s why in China, they handed over the day-to-day administration to collaborationist authorities [such as the Wang Jingwei regime],” says Lopes.

At the same time, she points to the fact that the Japanese wanted to treat Macao as a “rest and recreation station where they can go to the hotels, go to the casinos, have a good time and not really have the demands of running a fully occupied space.”

Although the Japanese military refrained from formally taking control of Macao as they did in the Portuguese colony of Timor, where they interned government officials in inhumane conditions, it did not stop them from exerting their influence on the city.

[See more: ‘Come to the city as often as possible.’ Author Jason Wordie reflects on Macao]

“They pressure the Portuguese administration [in Macao] to raid places that they suspect are involved in Chinese resistance,” Lopes points out. “They force the Portuguese administration to impose quite a strict censorship regime that, for example, targets explicit anti-Japanese news in the Chinese press and in the Portuguese press.”

Gunn also states that the Japanese used Macao as a channel to ship the much sought after mineral tungsten (wolfram) back home to manufacture weapon parts. As well, the city served as a base for the Japanese consuls and military police to relay intelligence to Guangzhou and Tokyo.

Given the presence of the Japanese in Macao and the surrounding occupied territories, it wasn’t surprising that the city became the target of multiple US bombings in 1945.

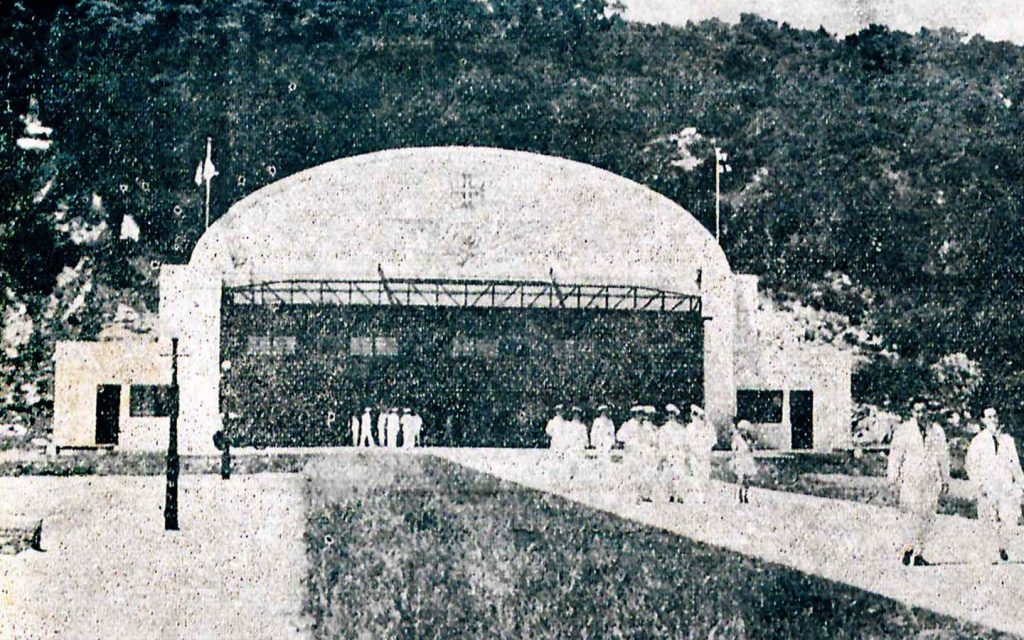

While the US maintained that the bombings were accidental, Lopes argues that “they seemed to know what they were doing,” as the attacks struck strategic targets such as harbour facilities, air hangers and fuel depots, sparing the lives of local civilians and refugees.

How did World War II shape Macao?

Following the end of the Second World War, the refugees that settled in Macao began to leave in droves. Some remained, including Stanley Ho, who cut his teeth in the city after arriving as a 21-year old refugee in 1941.

“His rise [as Macao’s casino tycoon] happens later, but the war experience is formative in the sense that it introduces him to Macao society, Macao’s circumstances, how its economy works and who are the important people in the community and so forth,” Lopes says.

This invaluable experience would later help Ho to manoeuvre through Macao’s business environment and co-found Sociedade de Turismo e Diversões de Macau (STDM) in 1962. Ho’s company would end up acquiring the monopoly licence that same year, dominating Macao’s casino industry for more than 40 years until the liberalisation of the market in 2002.

Ho was by no means the only individual in Macao who benefited from the war, as Guangdong-native, Ho Yin, the father of Macao’s first chief executive Edmund Ho Hau Wah, also came to his own after escaping to Macao from Hong Kong in 1941.

Once in Macao, Ho quickly put his business acumen to full use, co-establishing Banco Tai Fung in 1942. Ho’s skills in dealing with financial and community matters were quickly recognised by the Portuguese authorities, propelling him into the role of a prominent figure who would serve as an intermediary between mainland China and Portugal in the post-war period.

[See more: 25 at 25: Milestones in the history of the Macao SAR]

On a societal level, the war also greatly changed Macao’s business and cultural landscape, with Lopes noting that various schools, businesses and organisations relocated to the city.

“For example, Cantonese opera troupes also moved to Macao and for a moment, Macao was their main market because everything else was occupied around it,” she says.

Not all of these individuals and entities stayed in post-war Macao, however, resulting in what Lopes describes as a transformation that was not in a “continuum,” but rather one that was characterised by “some twists and turns.”

If anything, the fluidity of the war’s impact on territory reflects the multifaceted and nuanced nature of the conflict and Portuguese Macao.

“It’s definitely a period that should be remembered,” says Lopes. “It was quite complex and defies easy categorisation of good and bad and so forth, precisely because of this ambiguous position that neutrals always have.”