When Dr. Olivia Monteiro told me that she was preparing to research whether traditional Chinese medicine could be used to recover memory in mice, I immediately wanted to know more.

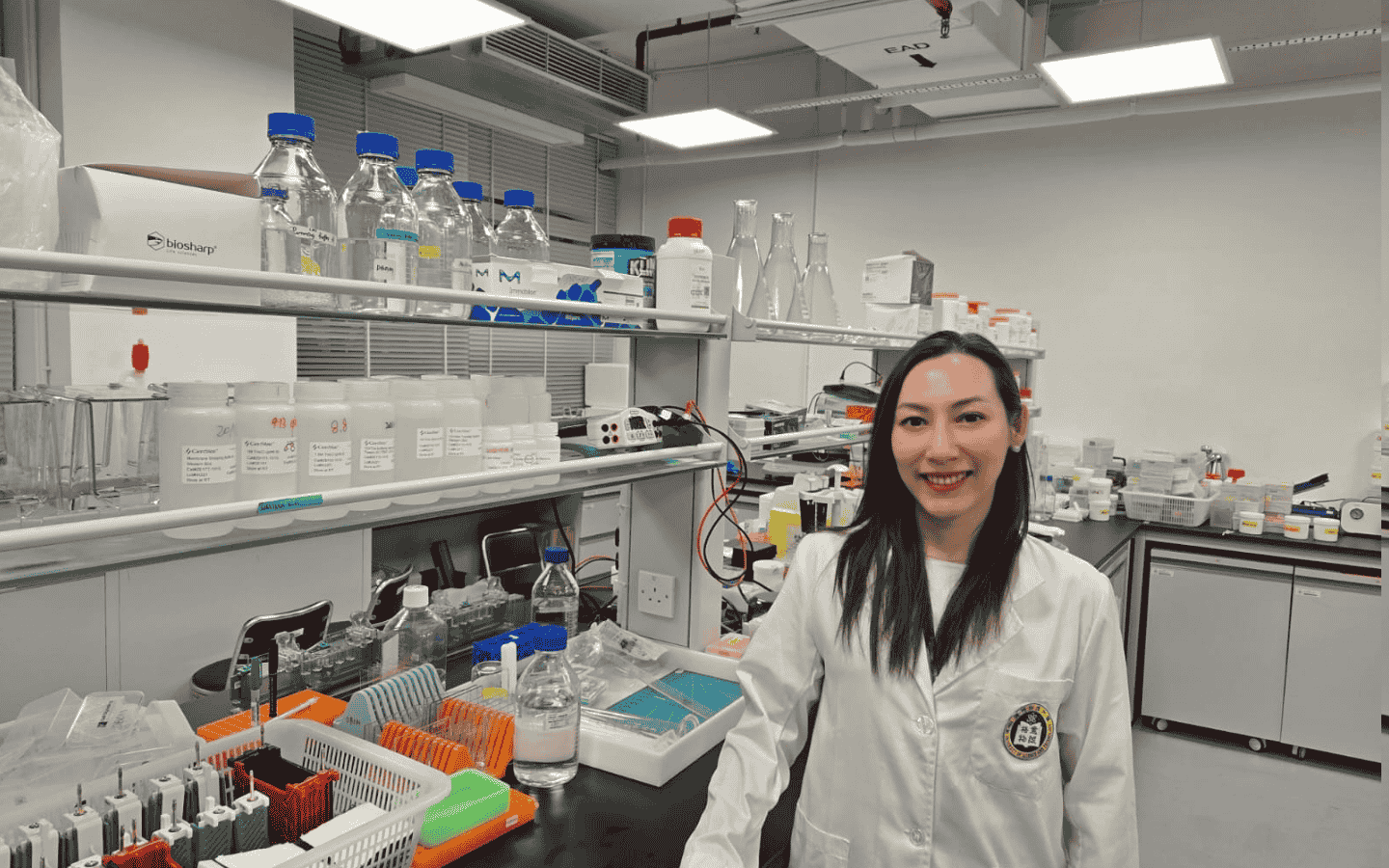

Monteiro is an assistant professor of pharmacology at the Faculty of Medicine at Macau University of Science and Technology. Her research primarily focuses on behavioural neuroscience – in layman’s terms, that’s the study of how our brain and nervous system influence our thoughts, feelings, and behaviours. Monteiro is also doing ongoing research on long Covid in the context of Macao and teaches the ethics of AI in medicine.

We met at the Liu’s Commerce and Industry Ltd building – its appearance, as the name suggests, seemingly more industrial than academic. But it’s also home to the MUST Liu’s Innovation and Technology Centre: a serious, no frills environment where Monteiro and postgrad students conduct their research.

Monteiro is Macanese, and born and raised in Macao. She was educated at Santa Rosa in Macao before going to school in the northern English town of Blackpool for her A-Levels. From there, she went to the University of Aberdeen in Scotland for her undergraduate degree in biomedical sciences, completed her PhD in Edinburgh, then worked as a research scientist in Dundee for ten years. Now, she’s been back in Macao for five.

Monteiro acknowledges the important role her multicultural upbringing and diverse education has had on both her research and career path. She describes her journey into neuroscience as an organic one, stemming from her innate desire to understand how things worked. “I think my upbringing definitely helped in that my parents are just very open minded as well and very liberal,” she says.

In fact, her parents’ open mindedness was crucial in developing her own open-minded approach to science. “I can’t just develop a question with a very fixed mindset and say that I must get this answer. That’s not how you do science.”

[See more: Shenzhen’s new Science and Technology Museum opens its doors]

It was in Blackpool that her interest in biology began. Her time there expanded her horizons as she discovered that there were seemingly no limits to the fields you could go into. Monteiro felt that in Macao there was less encouragement to explore diverse career paths, but in the UK young people were encouraged to be whatever they wanted. She had the epiphany that “You can do things that you’re interested in,” and her parents’ support was important for this sustained self-belief.

Following her interests, she went to university under the broad field of biomedical science, then discovered a particular interest in neuroscience during her PhD which led to a decade of memory-related research in Dundee.

However, the research on Chinese medicine’s potential to recover memory loss that fascinated me so much only began recently when she returned to Macao.

Research into memory enhancement wasn’t new to her, but the testing of Chinese medicine was. There was no research into the effects of Chinese traditional medicine at all when she was in Dundee. Monteiro acknowledges the unique position of having scientific and personal knowledge from Western and Chinese perspectives.

“I think that is the major benefit of having people like me, who have been trained in the UK, for example, to come back and bring my perspective on research and integrate with what has been established here, because Chinese medicine research is a lot more advanced in Macao and China compared to Europe and America,” she says.

It particularly struck me that our city’s multicultural identity made it an interesting place for researchers like Monteiro to bridge the gap between Western and Chinese medicine as well.

She expresses that a big advantage of researching Chinese medicine compounds is that a lot of them have already been used before by humans, with little or no harmful effects, so it is a lot easier to repurpose these compounds for treatment. Another cultural advantage is that there are a significant number of people in Macao and China that trust and prefer the holistic approach that Chinese medicine has, with some harbouring a sense of distrust over Western medicine.

Monteiro has been researching the effects of synthetic drugs and Chinese medicine compounds on memory recovery for the past few years. So far, she has only conducted tests on the effects of synthetic drugs and is continuing to prepare to experiment on mice with traditional Chinese medicine compounds, ultimately with the aim of comparing the effectiveness of Western and Chinese medicine.

[See more: Half of the world’s top ‘science cities’ are in China]

She puts mice in various controlled situations that she hypothesises will cause changes to their neural pathways, and sees whether synthetic drugs can alleviate symptoms of poor memory or even cure them.

Monteiro is not simulating significant events such as a traumatic event, but rather tries to recreate the seemingly small, mundane and inconsequential things like a human mother being distracted by her phone while looking after her child. She is currently designing a model mimicking this scenario, in which she puts in the cage something that interests the mother mouse more than her babies. The intention is to see whether the mother mouse’s sustained distractions from her children will result in the impaired development of the babies’ brains.

Monteiro’s research focuses on neurological rather than psychological changes. Firstly, the aim is to understand whether the brain changes on a molecular level, and whether that leads to decreased memory function for people that have had, say, distracted parents. Then, the testing of synthetic drugs and Chinese medicine will determine whether impaired memory can be recovered or improved.

Towards the end of our chat, Monteiro took the opportunity to encourage more women to pursue their passions and careers in STEM. “If you’re growing up as a girl and you don’t see any female scientists or female professors, then you don’t think that is an option.” She also spoke on the difficulties that women face in staying within STEM when they start a family, due to the lack of support to reintegrate into the field after childbirth.

When asked if there were enough women in science in Macao, Monteiro smiled and said, “We’re getting there.”