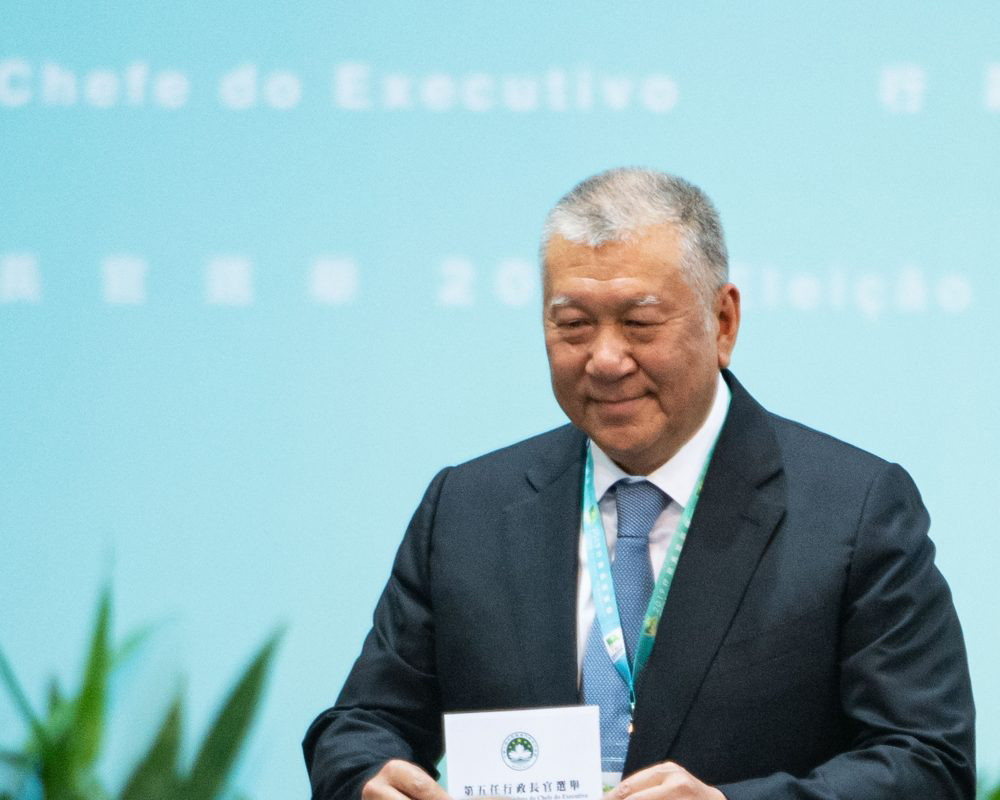

Macao has a chief executive (CE) designate. Sam Hou Fai, a 62-year-old former judge, had a handover meeting with incumbent CE Ho Iat Seng at Government Headquarters on 14 October, with Ho promising to do everything he could to smooth the transition of power.

[See more: It’s official: Sam Hou Fai is Macao’s next Chief Executive]

If his appointment is confirmed by the central government, Sam will officially take the reins on 20 December. With that date approaching fast, this is a good time to find out more about the role of the CE. Why do Macao’s leaders share a title with the heads of big companies? What’s their take-home pay? And are you eligible to become one yourself?

Read on to learn more.

Why does Macao have a chief executive and not, say, a governor?

It’s politics and optics. Governors are representatives of foreign powers. Chief executives answer to their stakeholders.

Macao used to have a governor when it was under Portuguese administration between the mid-16th century and 19 December 1999. The 127 men (and they were all men) who held this position had powers not unlike those of the current CE, in that they led the Macao government, as well as signed and promulgated laws covering the city.

The governor, however, served as a representative of Portugal, appointed directly by the Portuguese president and accountable to them, following consultation with the Legislative Assembly and other relevant stakeholders.

[See more: Portugal’s last governor says Lisbon has “a privileged knowledge” of China thanks to Macao]

In 1987, China and Portugal reached an agreement whereby Lisbon would return Macao’s administration to Beijing, with China agreeing to introduce a mini constitution (known as the Basic Law) that would preserve Macao’s unique institutions and way of life for 50 years after the handover. As part of this treaty, which was modelled after the earlier Sino-British Joint Declaration of 1984, both sides agreed the position of “chief executive” would be introduced to lead the government of Macao, which would be incorporated into China as a Special Administrative Region (SAR).

‘Chief executive’ is a weird term for a city’s leader, though. Where does it come from?

Actually, the title of chief executive is not new. In fact, its use can be traced all the way back to 1793, according to the Merriam Webster dictionary. While it can be used to refer to heads of big corporations, it’s correct to use it to refer in a general way to the head of the executive branch of a government. In that sense, many leaders around the world are, quite properly, “chief executives,” even if they adopt different titles such as president, prime minister, or chancellor.

[See more: Sam Hou Fai expands on his leadership plans for Macao]

Macao and Hong Kong are not unique in calling their leaders the chief executive. Indeed, the US President is sometimes referred to using this term. Other places that use the title include the Falkland Islands, which established an office of the chief executive in 1983, and Rodrigues (an autonomous island belonging to Mauritius), whose leader is known as the “island chief executive.”

But even so, the chief executive of Macao (or Hong Kong) is basically a mayor, right?

True, the role of a Macao CE is very similar to a mayor in any major city. They carry certain executive powers over their municipality and set specific policies. They nominate senior officials, set a budget, as well as work with the local law-making body to develop legislation.

However, the CE’s powers are far greater than a mayor’s and can overlap with those of a provincial or even federal leader due to Macao’s unique status as an SAR. For instance, article 50 of Macao’s mini constitution lists the various powers of the CE, which include the ability “to pardon persons convicted of criminal offences or commute their penalties in accordance with the law.” That isn’t something an ordinary mayor can do. Moreover, the CE has the ability “to appoint or remove presidents and judges of the courts at all levels” – another power that would not be delegated to a city mayor.

[See more: Sam Hou Fai critiques Macao’s shortcomings at his first town hall meeting]

Macao’s semi-autonomous status means that the CE is also in charge of key areas such as social security, immigration, and voting laws, which in other locations would normally come under the jurisdiction of a provincial, state or federal leader.

How much does the Macao chief executive earn and how does it compare to the salary of mayors of other big cities?

It’s a well paid job, alright. When the position was first introduced in 1999, the CE earned a monthly base salary of 129,740 patacas (US$16,148), with an additional 45,409 patacas (US$5,652) going towards social expenses. On a yearly basis, Macao’s leader had a total salary of 2.1 million patacas (US$262,000).

In 2014, a law was passed, boosting the CE’s total monthly salary by 10 percent, with the monthly base salary and social expenses being lifted to 199,796 patacas (US$24,868) and 69,929 patacas (US$8,579) respectively. In total, the CE currently makes 3.24 million patacas (US$404,600) per year.

[See more: Macao’s second highest official denies interest in the top job]

At the time, the authorities said the salary increase was made in light of factors such as inflation, private market salaries and the government’s finances.

In comparison to the mayors of other major cities, the Macao CE’s compensation package is very competitive. For instance, the current mayor of New York City, Eric L. Adams is in charge of an area that is 28 times the size of Macao, but earns only US$258,750 (2.08 million patacas) per annum, a difference of roughly 44 percent. Likewise, the mayor of London, a city with a population that is around 92 percent bigger than Macao, has a yearly paycheck of only £160,976 (1.69 million patacas).

I want to be Macao’s next chief executive. How do I apply?

The eligibility requirements to be Macao’s CE are not too demanding for a local resident, although winning the election is an entirely different matter.

As stated in article 46 of Macao’s mini constitution, you need to be a Chinese citizen and Macao permanent resident who is 40 years or above, having lived in the SAR for a continuous period of at least 20 years. Following the passage of the CE Election Law late last year, any potential future leader of Macao is also required to declare their loyalty to the city and mainland China.

[See more: Sam Hou Fai visit the Inner Harbour district on his third community walkabout]

If you fulfil those criteria, collect a nomination form from the Electoral Affairs reception desk at the Public Administration Building before the CE election nomination period. The tricky part is earning the endorsements of at least 66 electors and submitting a form that fulfils the requirements by the due date.

History has shown that in most cases one of the potential candidates ends up racking up a majority of the endorsements, leaving no room for other contenders to have their name printed on the ballot.

For more information, visit the official website (in Chinese and Portuguese).

Why do so many Macao CE candidates run unopposed?

Since May 1999, Macao has held a total of six CE elections. Apart from the first one, which saw Edmund Ho Hau Wah win by a landslide against his opponent Stanley Au (163 votes to 34 votes), all other polls were one-horse races, respectively featuring Fernando Chui Sai On, Ho Iat Seng and Sam Hou Fai.

The reasons for Macao’s CE elections having only one candidate are multi-faceted, with the mainland government’s explicit or implicit endorsement playing a key role. According to Sonny Lo Shiu-Hing, a veteran commentator of Macao and Hong Kong politics, “traditionally, Macao’s top leadership tends to focus on that kind of endorsement from Beijing.” He adds that Macao’s small size means that “politics tends to focus on guanxi [personal connections] and personal networks,” with “tacit or open support from Beijing” as a necessary element.

[See more: The government intends to amend the law on oaths of office]

Ieong Meng U, an assistant professor at the University of Macau’s department of government and public administration, echoes these reasons, noting that the selection of the CE “is a highly controllable process by the central government.” He mentions that “there are social norms or, you may say, a political culture preventing disagreement and divergence.”

Regarding this nomination cycle, Lo points out that many other potential candidates may have been “deterred from running,” as “the nomination period was turned into some sort of vigorous campaign” in which Sam’s position as the preferred or legitimate candidate was overwhelmingly solidified.

Indeed, potential candidates such as Jorge Chiang stood little chance with Sam receiving high-profile endorsements from the likes of former CE Edmund Ho Hau Wah (but more importantly also vice-chairperson of the 12th National Committee of the Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference (CPPCC)) and various heads of local associations.

On the question of whether or not Macao’s future CE elections will continue to lean towards having only one candidate, Lo admits that “it’s difficult to say,” as there are many elements at play. He explains that the situation in 2029 will ultimately boil down to three factors – the incumbent CE’s performance, his willingness to run and the determination of other candidates to take part in the race.