The Amazon rainforest’s capacity to generate rain for the South American continent is increasingly threatened by deforestation.

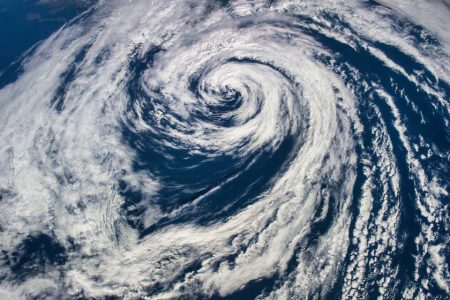

Trees in the world’s largest tropical rainforest transpire 20 billion tons of water per day, creating “flying rivers” of cloud that supply around 40 percent of rainfall in the South American region. Without such a large-scale injection of water vapour into the atmosphere, Brazil’s powerhouse agricultural sector would be in serious jeopardy, reports the New York Times.

In the face of the crisis, Brazil plans to launch the Tropical Forests Forever Fund (TFFF) at COP30 in November. The fund aims to direct resources to those who conserve forests around the world, such as indigenous people.

Money is key as those living in the Brazilian Amazon currently have few incentives to adopt a more sustainable way of life. As one expert told the Portuguese news agency Lusa, the livestock sector is more conservative, and purchasing land and destroying its vegetation remains “very cheap.”

[See more: Deforestation in the Brazilian Amazon soared 92 percent in May]

According to a MapBiomas analysis, the Amazon lost over 88 million hectares of forest – an area nearly the size of Venezuela – between 1985 and 2023. Formerly forested areas saw dramatic upticks in agriculture (+598 percent) and livestock (+298 percent) use. A newly published study demonstrates this loss of tree mass accounted for about 16 percent of the temperature increase since 1985 and nearly two-thirds of the rainfall decrease.

“We were expecting to see deforestation as a driver, but not this much,” Marco Franco, study lead and assistant professor at the University of São Paulo, told the Times.

The study looked at 29 sections of the Brazilian Amazon Basin, using large sets of satellite data to separate out influences like evolving landscapes, changing climate and shifting weather conditions between 1985 and 2020. On average, deforestation drove 74.5 percent of the decrease in rainfall, a figure that trended even higher in regions with more deforestation.

Drier conditions also contribute to wildfire risk, which in turn remove more trees, creating a self-reinforcing cycle. Last year, amid some of the worst droughts on record, fire burned across over 40 million acres of the Amazon. Farmers in areas bordering the forests, once among the most productive, are feeling the pinch. Farms in Mato Grosso struggled through 150 days straight without rain last year, and this year is likely to be worse.

“If you don’t have rainfall, then you don’t have rain for farming in Brazil,” Franco said. “This isn’t something for the future. This is already happening now.”