Between May 2020 and January 2021, five dead Chinese white dolphins were found on the coast of Macao. The incidents have aroused public concern about the survival of the imperilled marine mammals.

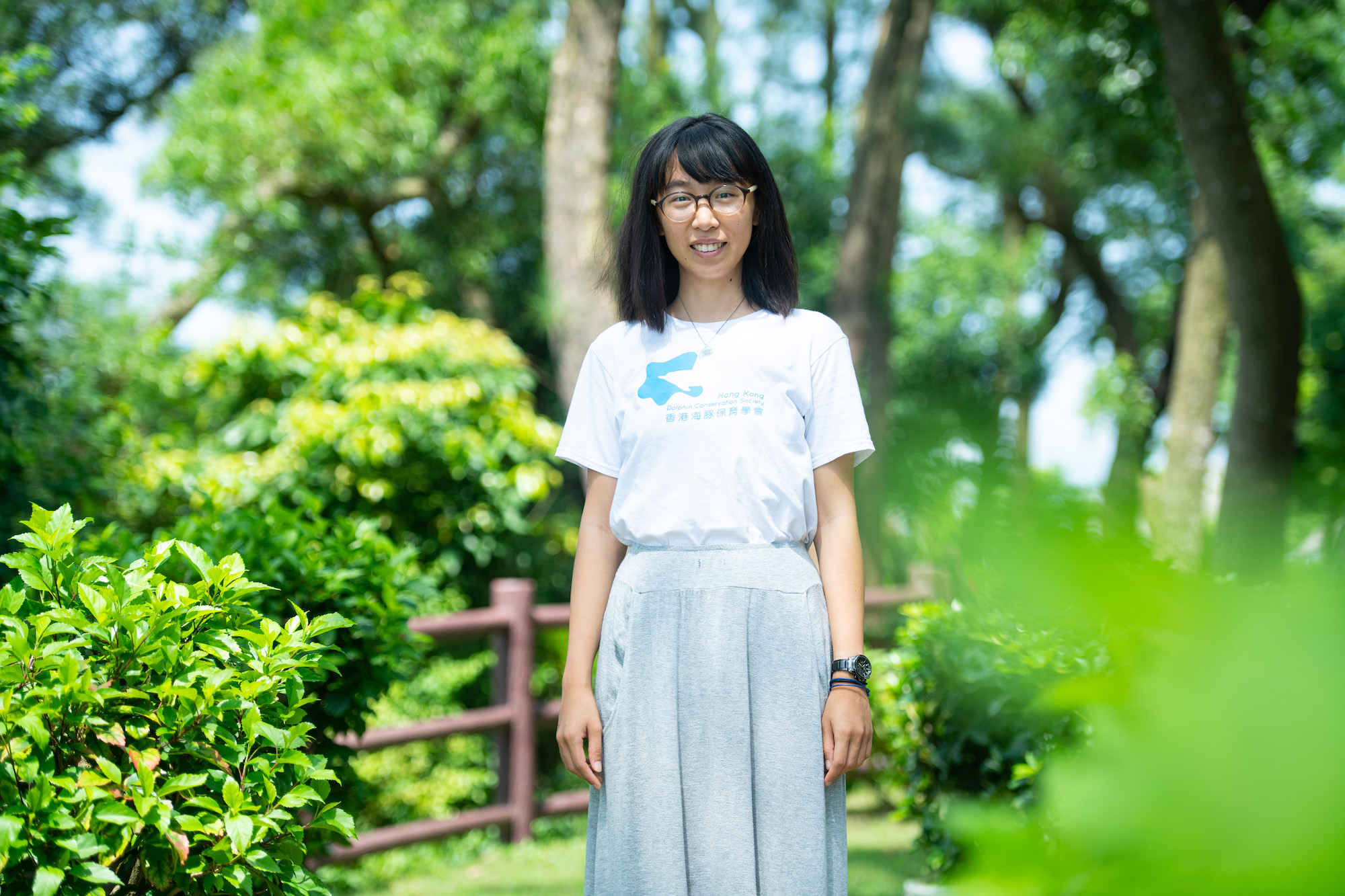

Viena Mak, a Macao-born marine researcher, believes that the combination of scientific data and persuasion by advocates is the key to saving the vulnerable animals. The 27-year-old graduated from the Chinese University of Hong Kong (CUHK) in 2013 with a degree in environmental science.

A year before her graduation, she started taking part in a long-term study on Chinese white dolphins and finless porpoises in the Pearl River Delta led by the Hong Kong Cetacean Research Project, a sister organisation of the Hong Kong Dolphin Conservation Society.

“I hadn’t been too into Chinese white dolphins or cetaceans [aquatic mammals comprising whales, dolphins, and porpoises] before,” she admits. “But out of curiosity, in 2012, I joined a two-day workshop hosted by the Hong Kong Cetacean Research Project at CUHK and I was shocked to learn about the adversities faced by these precious creatures.”

The plight of the Chinese white dolphin

Listed as a Grade 1 National Key Protected Species in mainland China, the Chinese white dolphin, which is actually pink, was named the official mascot of Hong Kong’s transferral of authority to China in 1997.

Even so, frequent construction and reclamation works and high-speed ferries churning through their habitats threaten their safety. Plastic debris and discarded fishing nets also pose a problem, as the dolphins could also accidentally inject or get tangled.

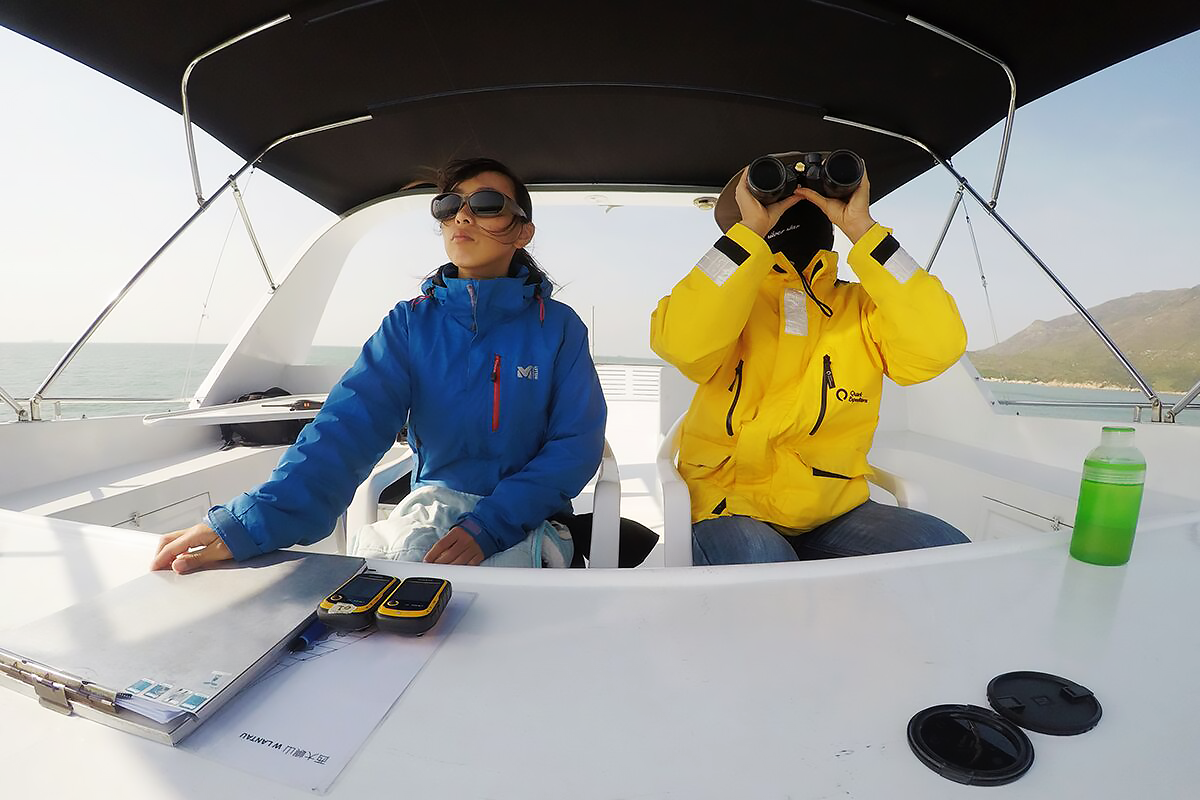

The more she learned, the more Mak felt determined to help the dolphins. She joined the Hong Kong Cetacean Research Project in 2012 and has been working for the organisation ever since. As a researcher, Mak climbs mountains and wades through water in order to track the dolphins living in the waters of Hong Kong. She observes their numbers, distributions and behaviours.

“I feel so happy every time I see a dolphin. It’s like visiting an old friend,” Mak says. She reckons she can now recognise more than 20 of them with her naked eyes, based on the shape of their dorsal fins and other distinctive features, such as colour patterns and scars.

However, the encounters are not always delightful. “About three years ago, I saw a Chinese white dolphin mother swimming with a dead young calf in the waters of Hong Kong. The mother was really scared of people. She immediately dragged the body down into the sea when she saw us. It was heart-wrenching.”

Although Mak and her team were not able to identify the reason for the calve’s death, she believes that such tragedies may indicate that polluted waters in the region have become inhospitable for marine mammals.

According to the latest statistics from the Agriculture, Fisheries and Conservation Department, only 37 Chinese white dolphins remain in Hong Kong. In Macao, studies have shown that there were at least 70 dolphins roaming the SAR’s waters in 2017, according to the Municipal Affairs Bureau. Meanwhile, a 2020 report conducted by Hong Kong Cetacean Research Project cited that newborn dolphins and young calves comprised just 2.5 per cent of the total Chinese white dolphin population sighted in Hong Kong, compared to 7.9 per cent in 2003. The declining birth rate may eventually lead to regional extinction, as there are not enough new dolphins to sustain the population, says the report.

Mak stresses that long-term measures are needed to protect and restore the marine habitats in the region, such as improving water quality, implementing speed restrictions on ferries, and reducing large-scale marine construction.

“Their future really lies in our hands. If we don’t step up to protect the species, our future generations may live in a world without Chinese white dolphins,” she says.

Protecting dolphins in Macao

A lot of her work may be in Hong Kong but Mak believes that it is also important to raise awareness about the protection of the Chinese white dolphins in Macao as reclamation work and high-speed ferries are also common in our waters.

Although the current Covid-19 control measures have hindered Mak from entering Macao, she actively participates in online and live-stream events geared towards the protection of the animals in Macao.

For example, Mak was a guest speaker at a documentary screening hosted by Macao Science Centre this August, where she shared her observations about the vulnerable dolphin population near the city’s waters and the threats imposed by humans.

She has also worked with the Macao Percussion Association for more than two years to conduct musical performances at several local schools. Combining percussion and storytelling, the performance is based on Red Moon, a picture book that depicts the challenges faced by dolphins in their habitats.

When the travel rules between Hong Kong and Macao are relaxed, Mak hopes that she can work with more schools in Macao to raise awareness on cetacean protection. “It’s important to plant a seed in the next generation and to help the teachers understand the situation, so that they can raise awareness,” says Mak.

When the activist receives positive feedback after events, it fuels her determination and keeps her moving forward: “I feel motivated when people are inspired by the events I host and want to help the dolphins. They make me feel hopeful.”

HOW TO HELP

By making eco-friendly choices and supporting activists’ efforts, anyone and everyone can help the Chinese white dolphins and our fragile oceans.

Speak up for the ocean:

– Sign an online petition co-organised by Hong Kong Dolphin Conservation Society and other wildlife NGOs to urge the Hong Kong government to designate at least 10 per cent of Hong Kong’s waters as marine protected areas. The petition ends on 30 September.

Adopt an eco-friendly lifestyle:

– Use chemical-free products such as home-made shampoo or enzymatic detergent made with natural fruit peels.

– Use reusable plastic products to reduce the volume of plastic debris that ends up in the ocean.

– Join beach clean-up events to help reduce garbage that could end up in the oceans.