Catholicism has had a long and colourful history in Macao that dates all the way back to the mid-16th century and the arrival of the Jesuit order, which used the city as a base to spread the Gospel across Asia.

On 23 January 1576, the city consolidated its status as the heart of Catholicism in the region when Pope Gregory XIII declared the establishment of the Diocese of Macao – the first Catholic jurisdiction in the Far East.

Following this milestone, the Macao church was tasked with supporting the work of priests across large sections of the region, including China, Japan, Korea and Vietnam.

In fact, the city’s role proved to be so pivotal that Jesuit missionary François de Rougemont (1624-1676) wrote in his book, Historia Tartaro-Sinica nova, that “we of the Society of Jesus […] were indebted to the grace of Macao…In particular the missionary works in China and Japan benefit the most from Macao and their development and maintenance rely on support from Macao.”

[See more: City of the Name of God: A guide to Catholic Macao]

While the Macao diocese’s work across Asia has been supplanted by local administrators in the centuries since, the city has remained true to its early Portuguese moniker of Cidade do Nome Deus de Macau (City of the Name of God).

For starters, the influence of Catholicism remains strong, as illustrated by the city’s array of churches, landmarks and Catholic-affiliated institutions such as the Ruins of St. Paul’s, the Chapel of Our Lady of Penha, Santa Rosa de Lima Secondary School and Caritas Macau.

Add to this is the city’s sizable population of nearly 33,000 Catholics, who keep traditions such as the various annual processions alive.

To mark the 450th anniversary of this historic and culturally important institution, here are five Macao Catholic stories you (probably) didn’t know.

Macao’s Catholic landmarks were defaced with Maoist posters and banners during the 12-3 incident

These days, it is hard to imagine Macao’s protected Catholic sites being vandalised. But just 60 years ago, these structures were defiled with political propaganda during the turbulence known as the “12-3 Incident.”

The name refers to the violent confrontations between the local Chinese and the Portuguese police that took place on 3 December 1966, resulting in 8 deaths and 212 injuries. The event itself was initially sparked by tensions over the then-Portuguese administrators’ refusal to permit the building of a left-wing school in Taipa, although there were other factors at play, including the spillover of anti-colonial sentiments and the Cultural Revolution in mainland China.

While the incident technically ended with the Portuguese authorities issuing an apology to the victims on 29 January 1967, the Cultural Revolution’s Red Guards continued to run rampant in Macao over the following months.

In a report published in the Catholic Weekly on 22 June 1967, Australian reporter Jack Spackman wrote that “the Church is suffering at the hands of the Red Guards in the small Portuguese colony of Macao…every church building, school and orphanage has been plastered with Communist slogans and posters.”

[See more: Turning hell into heaven: Macao priest Father Gaetano Nicosia embarks on the path to sainthood]

“The worst example of their poster art is the facade of the old St. Paul’s Cathedral,” he noted. “Today it carries posters wishing Chairman Mao Tse-tung a long life and others accusing the British of atrocities in Hong Kong.”

The Red Guards’ presence eventually waned, with the Australian journalist declaring in an article on 20 June 1968, “Church Triumphant in Land of the Red Guards.”

“Life slowly returned to normal in Macao and at last the Catholics were again able to take their faith out into the streets,” Spackman wrote. “Every stratum of Macao society, from the Portuguese governor to humble Chinese coolies, took part in the Fatima procession [this year].”

The Ruins of St. Paul’s are connected to secret tunnels

Every city has its urban legends and Macao is no exception. One long-standing tale claims that there are several secret tunnels linked to the former St. Paul’s College, the Catholic seminary complex that was razed after fire in 1835, leaving just the facade of its church, known as the Ruins of St. Paul’s.

According to the Macao Foundation’s Macau Memory history platform, there are two main versions of the tunnel legend. One of them claims that these passageways were built to house the gold that the Jesuits used to keep their operations running. Unfortunately, the entrances to the tunnels were sealed off after the fire that engulfed St. Paul’s College, resulting in the whereabouts of the money being lost to time.

Another version of the myth supposes that the tunnels were constructed as a place of refuge for the early Jesuit priests who tried to evade attacks on the churches from the less friendly elements of the Chinese population. (Interestingly, this tale would evolve into a local horror story involving a father and son who discover the remains of an old priest who starved to death after being trapped inside the tunnel.)

As for the locations of the tunnels, one of them is supposedly situated somewhere in Mount Fortress, while another can be found in Pátio da Mina. The third tunnel’s address is a little less believable, as some have linked it to places as far as Ilha Verde, Guia Fortress and Taipa.

[See more: Andrew Kim Taegon: The Macao seminary student who became a Korean Catholic saint]

Of the three tunnels, only the Pátio da Mina link has been discovered, with the head of the Macau History Association, Chan Su Weng, acknowledging its existence in a 2018 interview with MASTV.

Chan estimated that the tunnel had a history of around 300 years, with the Jesuits using it as a refuge site and a place to store treasures. The local historian said that the Portuguese administrators had attempted to open up the tunnel around the 1950s, but eventually kept it sealed due to safety concerns.

Still, the area has attracted the curious over the years, including a number of YouTubers keen to view the tunnel’s sealed entryway.

St. Augustine’s Church has a plaque linked to the abduction of a female minor

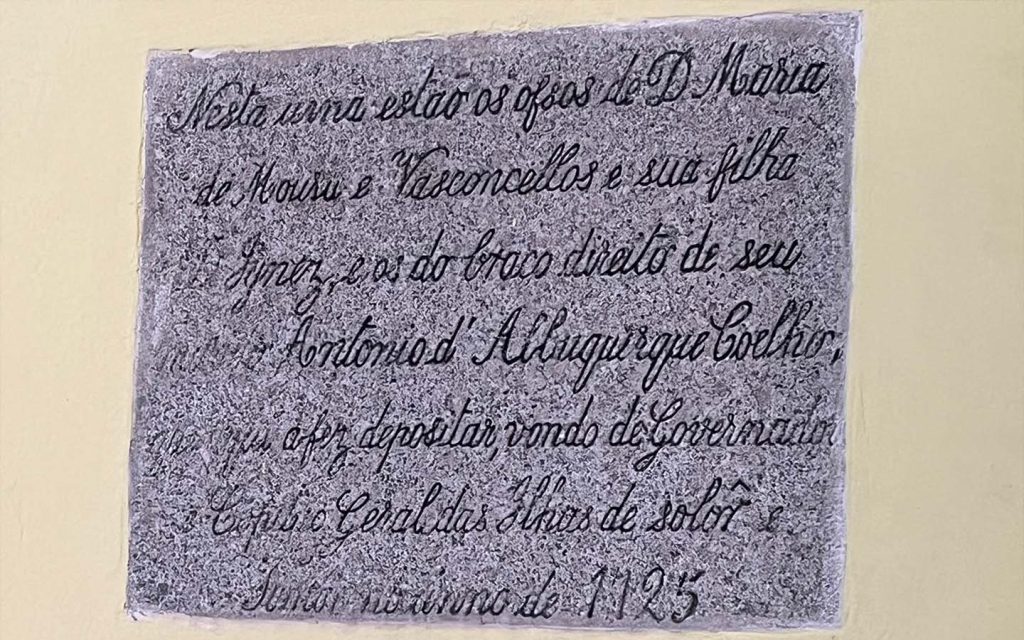

On the wall of St. Augustine’s Church, there is a rather unassuming memorial tablet that holds the ashes of three people – Macao’s Portuguese governor from 1718 to 1720, António d’Albuquerque Coelho; his child bride, Maria de Moura; and their daughter D. Ignez. While their names have largely been forgotten by most, the story between Coelho and Moura makes for unsettling reading.

Prior to becoming Macao’s governor, Coelho served as the captain of the ship Nossa Senhora das Neves (Our Lady of the Snows), which made its way from Goa to Macao in 1706. The ship, however, was damaged by a typhoon, forcing its crew to remain in Macao as it underwent two years of repair.

During that time, Coelho met Moura, a nine-year-old girl who had inherited a sizable fortune after the death of her parents – prompting Coelho’s avaricious attentions. Unfortunately for him, there was a competing rival for the girl’s inheritance in the form of Dom Henrique de Noronha, who had won the approval of Moura’s grandmother as a “suitor.” In turn, Coelho sought and obtained the backing of the influential Bishop of Macao, João de Casal, and the Jesuits.

In June 1709, Coelho decided to take matters into his own hands by forcibly taking the child to St. Lawrence’s Church where he pressured her into becoming his “betrothed.”

[See more: The Catholic church is canonising its first millennial saint]

Dom Henrique decided to exact revenge against the future Macao governor. In July 1709, Noronha’s Black slave attempted to shoot Coelho with a blunderbuss, but missed. After unsuccessfully pursuing the would-be assassin on his horse, Coelho passed through Rua Formosa where he was shot at again, this time by Dom Henrique from the window of a house. The bullet pierced through the elbow of Coelho’s right arm, with the future governor making a run by riding towards the Franciscan convent.

On the way, another slave tried to carry out a third assassination attempt, although that failed too. Coelho finally made it to the convent, but did not receive proper medical care until two weeks later, resulting in the doctor having no choice but to amputate his right arm due to gangrene.

Despite these sordid circumstances, the marriage of Coelho to Moura went ahead on 22 August 1710. Tragically, the 12-year old Moura died shortly after the christening of their second child, a son, on 27 July 1714.

St. Dominic’s Church was the scene of a 17th century crime

Originally built in 1587 before being reconstructed and expanded in the 17th century, St. Dominic’s Church has been an enduring part of Macao’s Catholic culture.

While the church has played host to various celebratory events such as the annual Procession of Our Lady Fatima, it has also borne witness to some of the darker parts of Macao’s history.

[See more: A series of videos about Macao’s Catholic history has been released]

According to the SAR government’s 2005 UNESCO World Heritage nomination document, the church saw the murder of a local sergeant by a mob in 1642. The official had unwisely voiced his support for the Spanish in public while the city was in the midst of acclaiming the Portuguese King John IV, who restored the country’s independence from Spain in 1640.

The sergeant attempted to escape by hiding in St. Dominic’s Church, but was found, resulting in his murder in front of the church’s main altar.

Macao was a place of exile for Catholic missionaries during the Chinese rites controversy

Early Catholic missions in the Far East were not always successful due to various reasons, including their failure to overcome language barriers, persecution from local governments, and the inability of missionaries to reconcile their beliefs with the local culture.

The latter gave rise to the so-called Chinese Rites Controversy, which saw Catholic missionaries in China debating throughout the 17th and 18th centuries whether Confucian rituals and ancestral worship should be regarded as religious or cultural practices. A religious designation would mean that Chinese Catholics would no longer be able to observe these aged-old traditions.

“The Jesuits argued that these rites were secular and compatible with Christinanity, while the Dominicans and Franciscans maintained that they were idolatrous and brought the issue to the attention of Rome,” says Jacqueline Xie, a University of Macau history researcher. “Ultimately, the papacy condemned these rites, resulting in restrictions and activities and straining relations between the Catholic Church and the Qing Dynasty.”

Indeed, Emperor Kangxi (reigned 1661-1722) responded to Rome’s obstinance by writing on 18 January 1721, “How can we speak to those narrow-minded Westerners about the grand principles of China? From now on, the Westerners may no longer practice their religion. It is now banned to avoid further trouble.”

[See more: Behind the relic: St Francis Xavier’s perilous mission to spread Catholicism across Asia]

Among those exiled to Macao was papal legate, Charles Thomas Maillard de Tournon, who remained under arrest in the former Portuguese enclave while Kang Xi dispatched an envoy to Rome.

Kangxi’s son and successor, Yongzheng (reigned 1722-35) showed very little sympathy for the Catholics as well, as he deported 30 missionaries to Macao on 24 August 1732.

Aside from being a place of exile, Xie notes that Macao was “a base for operations and a site for documenting and transmitting debates to Europe.” The academic points out that the city was “a gateway for Jesuits, Dominicians, and Franciscans compiling conflicting reports about Chinese rituals to send to Rome.”

Ultimately, the controversy would end up spanning roughly two centuries, with Xie noting that major papal rulings took place in 1645, 1704 and 1715, with “a partial reversal in 1939.” “These dates,” she says, “mark significant turning points when Rome condemned, reaffirmed and later relaxed its stance on Chinese ancestral and Confucian rites.”