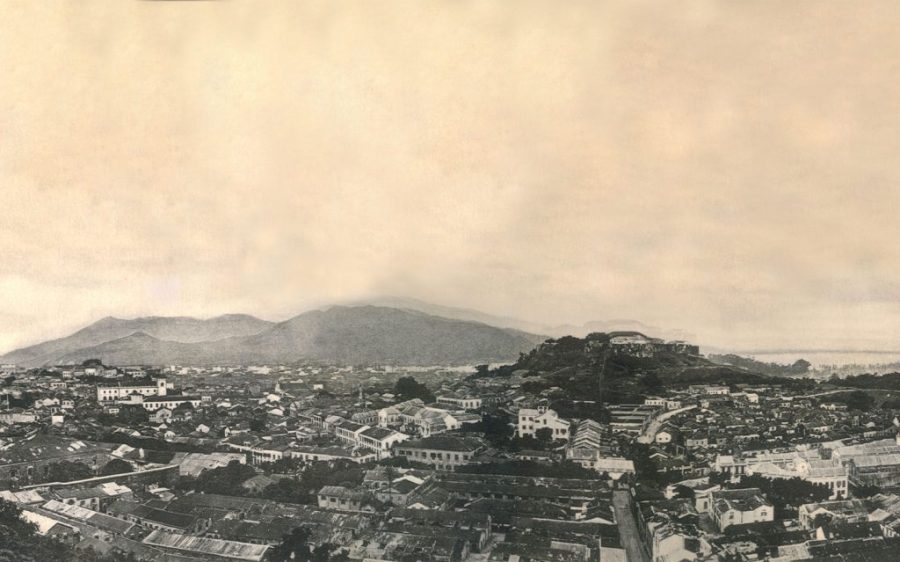

For hundreds of years, Macao has seen famous people come in and out of the city. Literary maestros, artistic talents, political pioneers and religious leaders have visited the territory regularly, some staying for a short while and others just passing through. Here are a handful of men and women who we can call both ‘famous’ and, at one time or another, a ‘resident’.

The Jesuit missionary

Jesuits are members of the Society of Jesus, a Roman Catholic order of priests founded by men like St Francis Xavier in 1534 to do missionary work. And in the mid-16th century, they set out from Europe and headed across the world to do just that. Far corners of the East were converted to Christianity, however, China took longer for them to reach. St Francis Xavier, for instance, died on an island near to Macao in 1552 before he could make it to the Mainland.

A successful attempt to reach the country and begin missionary work was later made by Michele Ruggieri and Matteo Ricci – leading to the eventual growth of Catholicism in China – but it couldn’t have been made possible if it had not been for Alessandro Valignano, who knew the Jesuits wouldn’t get far on the Mainland without a sound understanding of Chinese language and culture. So he moved to Macao, supervised the instruction of the missionaries and helped to introduce Catholicism to the East, from India to China and Japan.

Born into aristocracy in February 1539 in Chieti, in the Kingdom of Naples, Valignano excelled as a student from early on, obtaining his doctorate in law at the age of 19 from the University of Padua. He studied Christian theology further in 1562 and was admitted into the Society of Jesus in 1566. In 1573, he was sent to East Asia – a controversial move at the time as he would become an Italian supervising mostly Portuguese missionaries.

But his excellent work soon went before him. At the age of 34, he was appointed the papal representative to the Indian subcontinent through his role as Visitor of Missions, overseeing all Jesuit missions in Asia. He was first stationed in India but, in September 1578, he arrived in Macao and, while living in the city, he visited Japan three times, where he advocated for Japanese priests to be nurtured and treated equally to the European Jesuits.

One of Valignano’s greatest contributions to the cause was his work in founding St Paul’s College in Macao – which was part of the church complex that was destroyed by fire, creating what we see today as the Ruins of St Paul’s – in 1594. Here, the Jesuit university served to prepare Jesuit missionaries travelling east. In Macao, Ruggieri and then Ricci were sent to join him to study Chinese, at which they excelled. The two men became the first European scholars of China and the Chinese language.

During his life, Valignano, who certainly focused more on Japan than China but was nevertheless integral to the success of the later missions into the Middle Kingdom, managed to pave the way for a closer relationship between Asian and European people by advocating equal treatment for all. His legacies lie across Asia, not least in Macao. On 20 January 1606, he died in Macao and was buried in the Church of St Paul, where the Ruins of St Paul’s stand today.

The Swedish merchant-historian

Macao has been home to many well-known merchants and historians over the years – but few residents have been both. However, Anders Ljungstedt, in the early 19th century, became famous for his historical works in the city and for his success as a charitable merchant who sent money back to his homeland to help educate poor children. The Swede’s name is still remembered in the city for the important work he put into charting Macao’s colourful past.

Ljungstedt was born on 23 March 1759 to a poor family in Linköping, southern Sweden, and he attended the country’s Uppsala University for a short period before being forced to withdraw due to a lack of funds.

So, in 1784, he travelled to Russia and worked as a teacher for the next decade before returning back to his homeland. Back in Sweden, he was hired by the country’s government and served as a Russian interpreter for King Gustav IV Adolf, who ruled the nation from 1792 to his abdication in 1809, during the royal’s journey to Russia.

His move to Macao came about after Ljungstedt was hired by the Swedish East India Company, which took him to Guangzhou, where he stayed as a supercargo – a representative of the ship’s owner on board a merchant vessel, responsible for overseeing the cargo and its sale. The company, however, folded in 1813, so he began working as a merchant himself – a career he would follow until he died. Ljungstedt liked China and its climate so he stayed and settled in Macao, amassing a big fortune and sending a lot of money back to Linköping to help start a school for poor children.

Ljungstedt became extremely interested in Macao’s history after he settled. He researched the city’s past thoroughly and published a work that went on to be of great historical importance: An Historical Sketch of the Portuguese Settlements in China and of the Roman Catholic Church and Mission in China and Description of the City of Canton. It’s still seen as an important work today, with a new edition created as recently as 1992 in English. At the time, the merchant also became famous for being the first Westerner to refute the Portuguese claim that the Ming dynasty had formally ceded sovereignty over the territory.

During his life, the King of Sweden made Ljungstedt a Knight of the Order of Vasa – an honour awarded to Swedish citizens for their service to the state and society, especially in commerce, agriculture or mining – and in 1820 he was also appointed as the country’s first Consul General in China. He was painted by famous English artist George Chinnery during his days in Macao and he died on 10 November 1835 after never returning to Sweden since he set foot in China. He was buried in the Old Protestant Cemetery and, in 1997, the Avenida Sir Anders Ljungstedt was named in his honour, cementing this merchant historian’s place in Macao’s memory.

The missionary on a mission

A grave lies in the Old Protestant Cemetery next to St Michael’s Church in St Anthony’s Parish. The remains of an extremely important man lie within. Every year, Chinese Christians from across the world travel to the cemetery to lay flowers on Robert Morrison’s grave.

Robert Morrison is seen as the father of the Chinese Protestant Church. He gave 27 years of his life to Macao and Guangzhou and he is famous for translating the entire Bible into Chinese. He was born on 5 January 1782, in Morpeth, England, and he became a missionary with the London Missionary Society as a young man. He arrived in Macao in September 1807 and it looked like mission impossible – the Chinese were banned, under pain of death, from teaching their language to foreigners. After being expelled from Macao, he settled in Guangzhou, where he secretly learned Chinese from a few friends. Also in secret, he began to evangelise.

In February 1809, he was appointed translator by the East India Company and able to live comfortably in Guangzhou. Overcoming many difficulties, he completed his translation of the Bible into Chinese. In 1824, he returned to Britain and presented his large collection of Chinese books to University College, London. In 1826, he returned to Guangzhou – his small group of converts was growing in number. He lived some of that time in Macao again, where he continued to study Chinese and teach what he knew to others.

Morrison wrote widely in China, including works on Chinese grammar and numerous religious tracts and articles. He conducted services of worship in his own home, in English and Chinese. Between 1827 and 1834, he also conducted several funerals in Macao. His social life in Macao was limited, however, due to his poor health, his busy work schedule and his disapproval of Catholicism, the religion of the city’s Portuguese residents. He was also haunted by a moral conflict – while he was spreading Christianity, he made his living from the East India Company, which earned almost its entire profits from the illegal sales of opium. He was, it is said, never able to resolve this inner conflict.

In June 1834, Morrison prepared his last sermon. He was dangerously ill. On 1 August, he died at his home at the Danish trading house in Guangzhou at the age of 52. Only his son – John Robert Morrison, an important interpreter and adept government official in Hong Kong who translated the Treaty of Nanjing in 1842 and is buried in the same cemetery as his dad – was at his side. The next day his remains were taken to Macao and buried. Robert Morrison was a man of profound religious faith and enormous determination, becoming a model for thousands of missionaries who followed his footsteps into China.

The saintly resident

Saint Andrew Kim Taegon, the patron saint of Korea and the first Korean-born Catholic priest, once lived and studied in Macao. He was born in Solmoe in south-central Korea in 1821 and grew up in his native country – his parents were Catholic converts and his father was martyred in 1839 for practising Christianity, which was prohibited in Confucian Korea in the 19th century – and he was baptised while living in relative poverty at the age of 15 years old before heading to Macao.

In 1836, Kim travelled more than 1,200 miles in secret to get to Macao and enter St Joseph’s Seminary, which was built more than 100 years prior and had become one of the principal bases for missionary work across Asia. Kim got there on foot and in small fishing boats. Christianity was banned in Korea and in China, so the nearest place he could go to complete the studies needed to become a priest was Macao.

Kim underwent a gruelling six years of study in Macao in an environment that was foreign to him and in languages that were new to him. He had to learn many subjects, including Latin, Mandarin, theology, philosophy and the history of the Catholic church. When he arrived, he was just a teenager, living away from home and among Europeans and Chinese but he excelled and in 1842, he acted as an interpreter on a French warship. He was also present at the signing of the Treaty of Nanjing, also in 1842, which marked the end of the First Opium War between Great Britain and China.

Kim left Macao after 1842 and, after nine years of study, he was ordained a priest in Shanghai in 1844. He then returned to his native country to evangelise, which was an illegal activity. In June 1846, he was arrested after a failed attempt to smuggle French missionaries into Korea and on 16 September 1846, he was tortured near Seoul on the banks of the Han River before being beheaded. A statue of him stands in the Luís do Camões Garden in Macao, which has become a place of pilgrimage for thousands of Korean Catholics. On 6 May 1984, Pope John Paul II canonised Kim and 102 other Korean martyrs during a visit to South Korea.

The lady of letters

Picture the scene: it’s 1830 and an American girl of just 21 years of age stands on a small boat with her aunt in the moonlight. The boat is making its way up a quiet river and the girl stands in awe as she admires the lines of pagodas and boathouses – sights she has never seen or even imagined before. Both women are dressed as boys, wearing velvet caps and cloaks, and both are full of excitement as they become the first American women to head into the depths of what was then known as the city of Canton – now known as Guangzhou – a city that was strictly prohibited to any foreign females.

We know this story happened because the young woman, Harriet Hillard, wrote her experiences down in letters to her elder sister Molly – letters which survived and later made up one of the most interesting records of life in Macao at the time, told uniquely from a female perspective. Hillard, a woman of letters and a diarist, lived in Macao between 1829 and 1833. Her journal in the form of those letters ran to nine volumes, filling a total of 947 pages. In it, she describes Macao’s rich diversity, including the Portuguese Catholic life and the vibrant culture of the Chinese community. The anthology is now part of the Low-Mills collection in the US Library of Congress.

She was born Harriet Low on 18 May 1809, the second of 12 children of Seth and Mary Porter Low of Salem, Massachusetts. Her father was a wealthy merchant and owner of a successful shipping business. In 1829, her uncle invited her to accompany him and his wife – her aunt – to China. He worked in Guangzhou, while Hillard and her aunt lived in Macao. As the only single Caucasian woman in the city, she became a social hit and came to know many prominent people, including artist George Chinnery, who painted her portrait (below). Despite a strict ban on women entering the business district of Guangzhou, she and her aunt dressed like boys and went there. When the Chinese discovered them, they threatened to stop all trade in the city, so Hillard and, soon after, her aunt left within three weeks so no further damage to relations was done.

After she left Macao, she married an Englishman and settled in London, gaining the Hillard name. She had three sons and five daughters. After the failure of her husband’s bank in 1848, the family returned to the USA, moving in with Hillard’s father in Brooklyn, New York. Her husband soon became “unstable and sick” and was unable to work. He died in 1859 and Hillard died in 1877. But her letters live on.

The Portuguese poet

Symbolism was an important artistic movement in Europe in the 1860s, 70s and 80s. Originating in Belgium, France and Russia, the style – which loosely focused on attempts to evoke rather than describe, using symbolic imagery to signify the state of the artist’s soul – greatly influenced many following artistic movements. Poetry was at the heart of Symbolism and the Portuguese arm of the movement produced a number of great poets but none so celebrated as Camilo Pessanha, a Macao resident with a flair for verse.

Born on 7 September 1867 in the riverfront city of Coimbra, Pessanha was the illegitimate son of an aristocratic law student and his housekeeper, and the eldest of five siblings. His father, upon graduating in 1870, was appointed a public defender in the mid-Atlantic Azores archipelago so the family moved there before moving once more in 1878 to Lamego in northern Portugal, where Pessanha completed his basic schooling.

Following in his father’s footsteps, he entered law school at Coimbra University in 1884. A year later, he wrote his first poem, “Lúbrica” – which translates to ‘Lascivious’ in English. This was the beginning of his career as a poet and some of his early works were published in local newspapers.

Pessanha, who had been in frail health due to depression, was fascinated by the East so, in August 1893, he applied to be a philosophy teacher at a newly established school in Macao. He was appointed to the role on 18 December and sailed out the following February, arriving in the territory on 10 April 1894. Immediately, many people thought him eccentric and his union with a Chinese concubine who he bought in 1895 raised many eyebrows but despite this, he became a respected teacher of philosophy, history, geography, Portuguese literature and law.

He had a son with the concubine a year later and, over the following years, he became a central figure in Macao’s cultural, political and civic world. During his time in Macao, he also met the “Father of the Nation”, Sun Yat-sen. There’s even photographic proof that points to evidence of good relations between the two men.

Pessanha didn’t really have a claim to fame until 1916 when his innovative Symbolist poetry was published in the progressive magazine Centauro. His works then became known and loved in Portugal and further afield, including his celebrated poetry book Clepsidra, which was published in 1920. The imagery and musicality in his verses caught the eyes and hearts of many later poets and his works influenced a whole host of Modernists. Pessanha also had the unique talent of re-writing his works from memory and also used to give many of his favourite poems to close friends.

Nominated a public defender in Macao in 1900, then a judge, later on, Pessanha passed his time in the city by composing poetry and immersing himself in the local culture. This culture became incorporated into his writings and also earned him much respect as a European authority on Chinese culture in the territory. Sadly, however, he also had a penchant for opium and on 1 March 1926, he died from tuberculosis which developed due to his addiction to the drug. He is buried in the Cemetery of St Michael.

The prolific composer

Music came to Macao in the first half of the 20th century in the form of gifted composer Xian Xinghai. The talented writer was born in a boat in Macao’s harbour and his mother earned a meagre living ferrying goods from the city to Zhuhai but he overcame poverty and prejudice and went on to study music in Paris, later writing the most famous piece of Chinese music composed during the Pacific War. He lived a short but dramatic life. During his 40 years, he wrote two symphonies, a violin concerto, an opera and nearly 300 songs, including his masterpiece, the ‘Yellow River Cantata’ in 1938. It became the battle hymn of China during the war with Japan and has had a lasting impact on modern Chinese music.

Xian was born on 13 June 1905 into a family of boat people. His father died when he was young, so he was taken by his mother from place to place, including Singapore, where she worked as a laundress to provide her son with an education. He moved from there to Guangzhou, studying at Lingnan University, where he developed his musical interests. He later studied in Shanghai before heading to France to study music at the famous Paris Conservatory in 1931.

In 1935, he returned to China and in 1938, he moved to Yanan, where he composed the epic ‘Yellow River Cantata’ in just six days and nights of intense work in a cave. It came to be sung by Chinese soldiers and civilians to raise their spirits during dark hours of conflict. He later moved to Moscow and then Almaty, the then capital of the Soviet Kazakh Republic. In the spring of 1945, he caught pneumonia and later died in a Moscow hospital on 30 October 1945, aged 40.

Today, Macao remembers Xian well with Avenida Xian Xing Hai, which runs through the Nape district, next to the city’s Cultural Centre, named after the composer. There’s also a statue of him at the avenue’s junction with Rua de Berlim. And the Cultural Affairs Bureau is converting two houses in Rua de Francisco Xavier Pereira into a museum in his memory, plus the city’s Post Office has also issued stamps in his honour. Xian’s life was certainly full of suffering and difficulties – but his music and memory live on forever.