When Singapore gained self-government from Britain in 1959 (a step on the path of its eventual independence from the Federation of Malaysia in 1965), nobody voiced fears that it would become “just another Southeast Asian city.”

Similarly, when the Union Jack was lowered in the Bahamas in 1973, there were no concerns that the Bahamas would become “just another Caribbean archipelago.”

The former Prussian possession of Danzig was given over to Polish sovereignty after World War II and renamed Gdańsk. No one fretted that its destiny was to become “just another Polish town.”

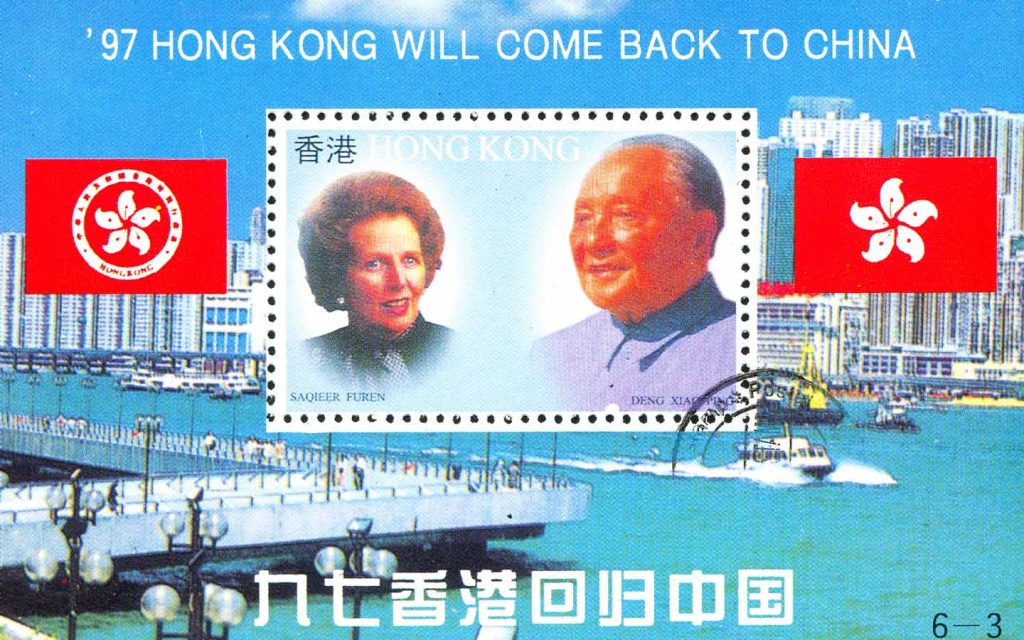

However, since the return of Hong Kong and Macao to Chinese sovereignty (in 1997 and 1999, respectively) it has been commonplace to warn that either SAR is fated to become “just another Chinese city” – or words to that effect – if Beijing does not maintain the high degree of autonomy promised to both as part of the handover arrangements.

Hong Kong is “nearly indistinguishable from any other neon-lit city on the Chinese mainland,” the US Congressional-Executive Commission on China wrote in its 2024 annual report (seemingly unaware that neon hasn’t been used for illuminated signage, on a commercial scale, since the 1970s).

[See more: The Internet asked, ‘Is it Macau or Macao?’ and we answered]

In a lengthy feature published on the BBC’s Chinese language website last December, one analyst said that Macao was becoming “less unique” and like “some third- and fourth-tier Chinese cities.” In February 2024, a Bloomberg Opinion columnist dismissed Hong Kong as “yet another Chinese city.” A month earlier, the Economist, under the pithy rubric “Westerners out, Chinese in,” lamented that “Hong Kong is becoming less of an international city.”

The disparaging phrase is so ubiquitous that it has been internalised by Macao and Hong Kong residents themselves. “I am afraid that it’s increasingly inevitable that Macao will eventually become just another Chinese city,” then Macao legislator Sulu Sou told the Agence France-Presse in 2019. Martin Lee Chu-ming, a leading democracy campaigner in Hong Kong, made similar remarks, telling the media that “we fear Hong Kong will become just another Chinese city.”

It seems that the term is mostly used by those who think that Beijing has done a bad job of keeping to the “One Country, Two Systems” political formula that governs its relations with the SARs. But regardless of where you stand on that debate, saying that a place is “just another Chinese city” comes freighted with geopolitical, ethnocentric and even racist baggage – at least according to some analysts.

So what does the phrase really mean?

Differing views

According to Asian history researcher and the author of Fortune’s Bazaar: The Making of Hong Kong Vaudine England, “just another Chinese city,” has “a whole spectrum of possible meanings” that are contextually based.

She tells Macao News that some Hongkongers will use the phrase positively – as did a letter writer to the South China Morning Post, who said “We are a Chinese city and we should be proud of it.”

For others, she says the phrase signifies an awareness that “Hong Kong is different and has had a different history, and is not the same as cities in mainland China, which have been through the whole process of the Chinese Communist Party victory in 1949, the famine, the Cultural Revolution [and] everything since then.”

[See more: The internet asked ‘Is Macao safe?’ and we answered]

From England’s perspective, it also harks back to Hong Kong’s distinct history as an entrepôt and melting pot for people of different ethnicities and racial backgrounds, who helped to mold the city’s unique identity. “It is the descendants of those early migrants who were for the first 100 years of Hong Kong’s existence as a city…quite fundamental to shaping the nature of the place,” she says.

However, Hong Kong University politics professor Sonny Lo Shiu-Hing views the phrase “just another Chinese city” as one that carries a dismissive and even derogatory undertone that is underpinned by what he terms “deep-rooted biases” against China.

According to Lo, the expression stems from the stereotype that “mainland Chinese cities tended to be backward politically, economically and socio-culturally,” and is tantamount to a slur like “locust” (蝗蟲), an insulting term used in Hong Kong for mainland Chinese, or “chee-na” (支那), a derogatory Japanese label for China that was provocatively revived by anti-China protesters in Hong Kong.

Chandran Nair, the founder of the Hong Kong-based think tank, Global Institute for Tomorrow and the author of Dismantling Global White Privilege: Equity for a Post-Western World, agrees with Lo’s view, telling Macao News that the phrase is a manifestation of the West’s sense of its own superiority and reinforces racist Western ideas of China as “oppressive,” “old” and “not civilised.”

“Apparently, Western cities uphold something much more upright and humanistic,” Nair says wryly, “without actually appreciating that the cities in China, and other older civilisations like India have much longer, much deeper cultures.”

Lo argues that people who employ this phrase often carry “biased” or “unquestionable” assumptions of “the good old days of [pre-handover] Hong Kong and Macao” being “much better than the current and future Hong Kong and Macao.”

He tells Macao News that some “believe that political transformation of Hong Kong and Macao must be bad, especially with regard to how political activists were treated in Hong Kong in recent years and how some political activists were disqualified in elections,” adding that the expression “just another Chinese city” reflects the ethnocentric views of Western critics who “tend to see their own political system as far more superior.”

England disagrees, and says she considers it “bizarre” to cast the expression as “racist,” as she simply sees it as a statement asserting Hong Kong’s distinct history and identity. “I don’t think it needs to be dressed up in any further ideological or complex theories about race or boring party politics,” the author says. “Different historical processes produce different cultures and communities and are produced by different cultures and communities.”

[See more: The Internet asked, ‘What is Macao chicken?’ and we answered]

But Lo points out that it is precisely the phrase’s failure to take China’s different cultures and communities into account that make it offensive. He is critical of the expression’s implication that all Chinese cities are uniform, which he says could not be further from the truth. From Shenzhen (China’s tech hub) to Xi’an (the ancient capital of China, brimming with various historic relics and sites), China’s cities exhibit astonishing variety.

Nair holds a similar view and believes that the repeated use of such language is a form of “mind capture” that helps to reinforce the “racist” Western viewpoint that Chinese cities are “all the same, oppressed, characterised by surveillance, not safe” and “don’t have any international flavour.”

“The agenda is to vilify, to demean [China]…[and] capture the minds of young Asians,” Nair argues, and to persuade “the minds of a whole generation of young Hong Kong people to think that China is a bad place.”

The uniqueness of Macao and Hong Kong

All three commentators are in agreement on one point, however: the value of Macao and Hong Kong to mainland China lies precisely in their difference from the rest of the country.

Nair says he has had conversations with senior mainland officials in Hong Kong, who told him they were “determined that Hong Kong should retain its own unique features.”

He adds that allowing Macao and Hong Kong to continue operating under a different system from the mainland serves the interests of the central government, as it helps to promote international trade and commerce, without “that system infiltrating the entire nation,” which operates under “a different political system.”

Indeed, Chinese President Xi Jinping praised the “One Country, Two Systems” policy during his visit to Macao last year, calling it “a good policy that serves the noble cause of building a stronger country and achieving national rejuvenation” and one that “must be adhered to for a long time.”

Lo points out that 156 years of British administration in Hong Kong and 442 years of Portuguese governance in Macao have resulted in the two cities developing “hybrid systems” of thought, culture, the economy and law – and that such systems are highly beneficial to their respective hinterlands

[See more: The internet asked ‘How big is Macao?’ and we answered]

“I think the distinctiveness of Hong Kong and Macao will not disappear,” Lo argues. Instead, the “resilience” and “adaptation” of the two SARs’ hybrid systems will persist,” with both cities helping to transform China’s Greater Bay Area and vice versa.

England believes that the freedoms enjoyed in Hong Kong are an inherent part of its identity and status as a cosmopolitan hub and are important to the city’s continued prosperity.

“I’m sure they [the administrators of Hong Kong] want to stay aware of what is necessary to maintain its status as an international trading city,” she says. “Otherwise, who wants it?”

For now, it seems the use of the phrase “just another Chinese city” is set to continue – at least by China’s critics. So is the feeling that the expression must be challenged on grounds that have nothing to do with politics. “I don’t give [the phrase] any oxygen,” Nair says. “We have to invalidate it as a racist depiction of the entire Chinese nation with a hidden agenda.”