Macao is undeniably a small city. As of 2023, it covered an official area of 33.3 square kilometres, which, for comparison, is 22 times smaller than Singapore (734.3 square kilometres) or roughly 33.5 times smaller than Hong Kong (1,114.57 square kilometres). But believe it or not, it was once even smaller.

“Macao in the beginning, when the peninsula was first settled by the Portuguese, was about three square kilometres…[but] now it’s about 30 square kilometres,” says Thomas Daniell, a Kyoto University professor who served as the head of the Department of Architecture and Design at the University of Saint Joseph (USJ) between 2011 and 2018. “Part of that is because Taipa and Coloane were added to Macao, but even so, more than 50 percent of Macao’s territory is now reclaimed land.”

[See more: The Internet asked, ‘Is it Macau or Macao?’ and we answered]

Spurred by rapid urban development and a growing population, Macao’s land has been expanding bit by bit for more than a century. In 1999, the year of the city’s handover from Portugal to China, the SAR’s area stood at 23.8 square kilometres. A decade later, this figure had grown to 29.5 square kilometres, and by 2019, the number had once again risen to 32.9 square kilometres, representing an increase of around 38 percent in the course of just two decades.

The growth of Macao’s land area over time

Large-scale reclamation began taking place from the 1860s onwards, with Daniell pointing out that it can be divided into four main stages.

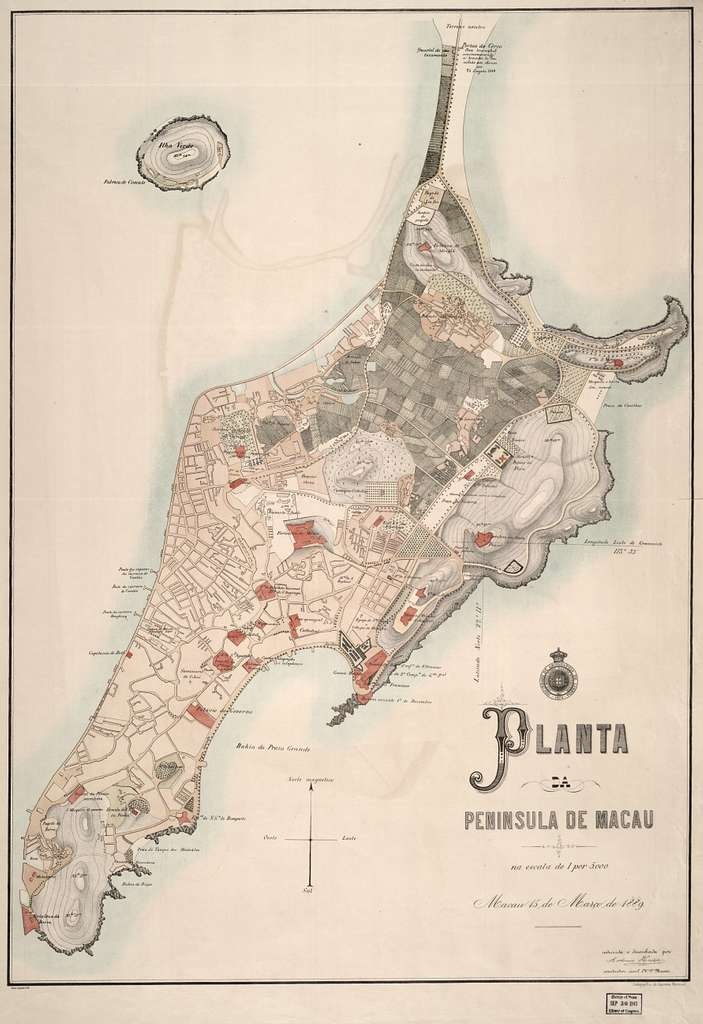

The first, from the 19th century to the early 20th century, gave rise to a considerable amount of new land along the Inner Harbour and in the area that now constitutes the Northern District. In fact, Fai Chi Kei, Toi San, Areia Preta and the Hipódromo, which form a significant portion of the northern part of Macao, were all artificially created. Most of the coastlines along the Macao Peninsula were also pushed forward significantly during this period, with the assimilation of the offshore island of Ilha Verde into the Macao peninsula being one of the most notable examples.

Nowadays, there is very little on-site evidence left to suggest that these sites were formerly coastal areas or bodies of water, although some vestiges do remain, as seen in the Chinese names of Inner Harbour streets such as Rua do Almirante Sérgio (河邊新街, which translates to New Riverside Street), Rua das Lorchas (火船頭街: Steamboat Wheelhouse street) and Rua do Guimarães (海邊新馬路: New Seaside Street).

The subsequent two stages of reclamation saw the expansion of the Outer Harbour area through the development of the reclamation sites known as ZAPE (Zona Aterro da Porto Exterior) between the 1920s and 1930s, and NAPE (Zona Nova de Aterros do Porto Exterior) in the 1980s.

“ZAPE [and] NAPE…were all [originally] intended as places for people, for housing and hospitals and schools and so on,” Daniell notes. “But they largely got taken over by casino developments.”

[See more: The internet asked ‘Is Macao safe?’ and we answered]

One such development included the Lisboa hotel and casino, which became the first casino to be established on reclaimed grounds when it was completed on the southern side of ZAPE. NAPE would see the building of similar gaming facilities as well, with the development of Sands Macao in 2004 – the first foreign-owned casino in Macao.

The fourth major phase of reclamation occurred between the 1990s and 2000s and resulted in the waters between Taipa and Coloane being converted into a 6 square kilometre body of land known as Cotai. It too would share a fate similar to ZAPE and NAPE, with integrated resorts and casinos being built in the area.

Land reclamation has continued into the present day, as evident from more recent projects such as the Zhuhai-Macao Port Artificial Island, New Urban Zones A, B, C and E, as well as the future expansion of Macao Airport, which will be built on reclaimed land that is set to be developed in the second half of this year.

Macao’s sea territory has grown too. The central government gave Macao jurisdiction over 85 square kilometres of its surrounding waters in 2015 for the purpose of economic development, a move that essentially tripled the SAR’s size by three fold.

Unlike ZAPE, NAPE and Cotai, however, newer reclamation initiatives will not be geared towards the expansion of Macao’s gaming industry. Instead, Daniell explains that “since the handover, the Beijing government has been quite strict about not allowing new casino developments in future reclamations,” pointing out that “they want the new reclamations to support the daily life of Macao citizens.”

Indeed, Beijing continues to hold the final say when it comes to the approval of any new reclamation projects. As the then Chief Executive Chui Sai On said on the expansion of Macao marine boundaries in 2015, “Any fresh proposal for land reclamation involving Macao’s newly demarcated waters will be reported to the central government, and there will be no gaming venues or commercial gaming activities in such areas.”

Reclamation and the future of Macao

While the reclamation projects of past and present have greatly enhanced Macao’s economy and the livelihood of its residents, they have not been without their problems. For starters, Daniell notes that “the ground [in parts of ZAPE and NAPE] is subsiding …damaging the sidewalks and affecting some of the buildings because the reclamation was not as solid as it should be.”

Reclamation has also substantially reduced the mangrove forests that were once present along Macao’s coastlines. Daniell, however, says that the impact of land reclamation on the environment should not be overstated, as such projects may “be a big shock to the natural environment [at first], but very quickly get absorbed and adapted,” resulting in the environment’s recovery.

As for the future of land reclamation in the city, the SAR could in theory continue reclaiming land indefinitely. Daniell notes that despite the exorbitant costs involved in creating new reclamation, there will always be a demand for such projects as the building of apartments and casinos have reaped considerable economic returns. As well, there will always be pressure for more land so long as the SAR maintains distinct borders from mainland China.

[See more: The Internet asked ‘What is Macao’s currency?’ and we answered]

However, Chief Executive Ho Iat Seng has previously stated that his administration is pivoting away from land reclamation. Instead, the government aims to create a “second Macao” in Hengqin. The process that has already been taking place in such developments as the Macau New Neighbourhood and the implementation of the closed customs regime at the beginning of March.

Although it remains to be seen whether or not large-scale reclamation projects will continue to have a place in Macao in the long run, there is little doubt that the man-made land created through these endeavours have made artificiality a fundamental part of Macao’s identity in the same way that the city’s Chinese and Portuguese history are an inseparable part of it.

While this artificiality may carry negative connotations to some, Daniell is of the opinion that the city should embrace it. “I don’t think it’s something to be embarrassed about,” he says. “I think it’s a wonderful necessary part of the world and Macao should be proud of it.”