Start from Sai Van Bridge and head south.

Past the fast cars and faster talkers of Taipa’s town centre, past the hopeful gamblers and fastidious hoteliers on Cotai Strip. Take a left when you reach the Ilha de Coloane. There, tucked in the corner of the island and overlooking the Pacific Ocean, is Nossa Senhora Village, a settlement dating back to 1885.

Today, Nossa Senhora Village is a quaint collection of ochre-coloured buildings that attracts visitors wanting to experience the less glitzy side of Macao. Its brightly-hued walls, delicate marble statues and the crawling roots of century-old trees present the East-meets-West aesthetic the city prides itself on – reflecting its time as a Portuguese-administered territory.

But just a few decades ago, Nossa Senhora Village was much less inviting.

“Abandon all hope, ye who enter here” – that’s how Father Gaetano Nicosia described the enveloping sense of despair the town seemed to exhale when he first arrived in what was then known as the Ká Hó Leprosarium.

[See more: Wartime Macao: Neutrality, refugees and riches]

Ká Hó represents a troubled time in Macao’s history of Hansen’s disease, formerly known as leprosy. The chronic affliction, spread by Mycobacterium leprae bacteria, can cause physical disfigurement, blindness and paralysis, among other symptoms.

While modern research shows that the vast majority of people are immune to it, Hansen’s disease sufferers have long been stigmatised due to the mistaken belief that it’s highly contagious. To avoid the dehumanising connotations attached to the term “leprosy,” the disease has been increasingly referred to as Hansen’s disease, named for the doctor who identified the causative bacteria. But until the later part of the 20th century, patients were often forcibly quarantined in places such as Ká Hó, condemned to spend their lives segregated from society.

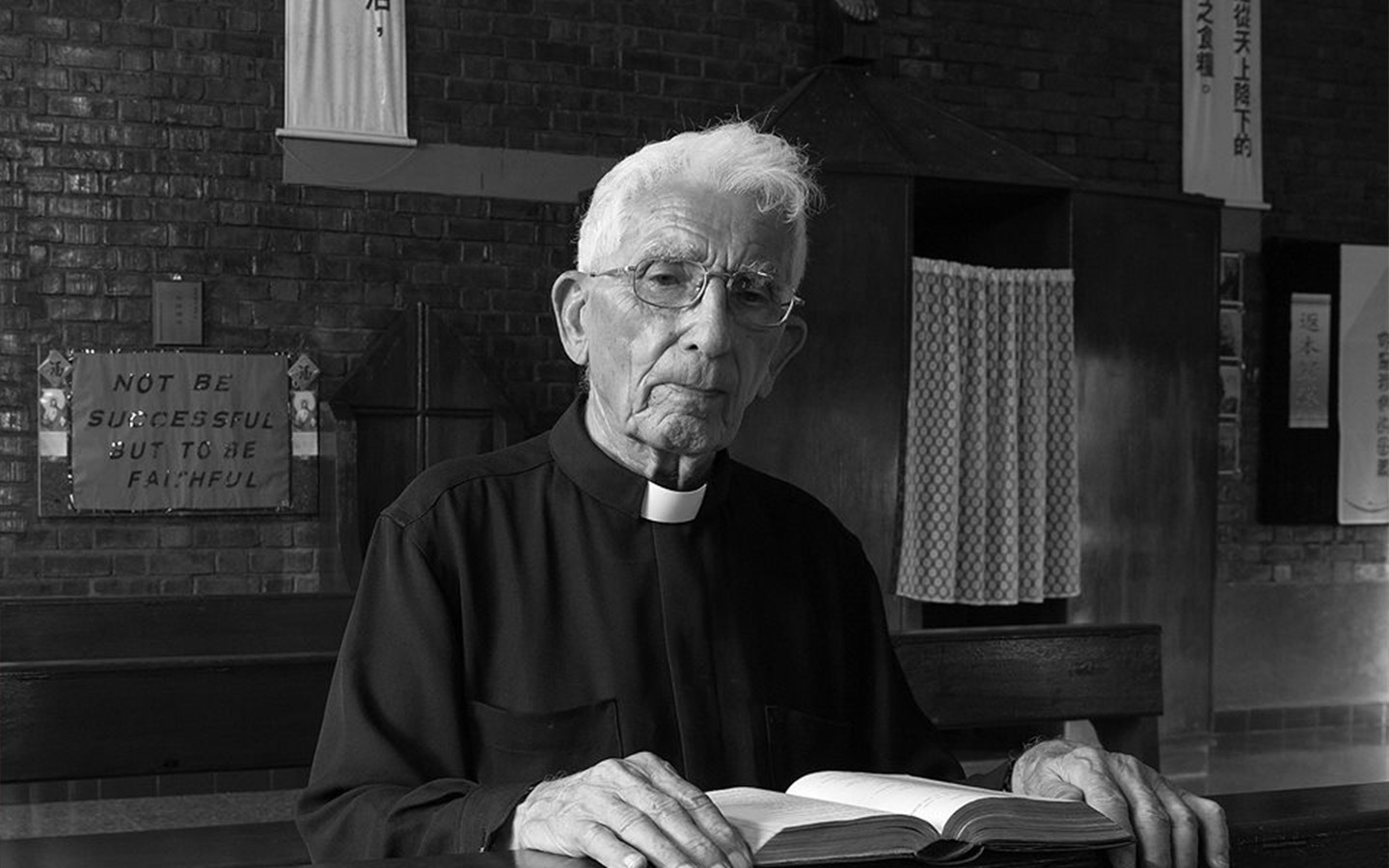

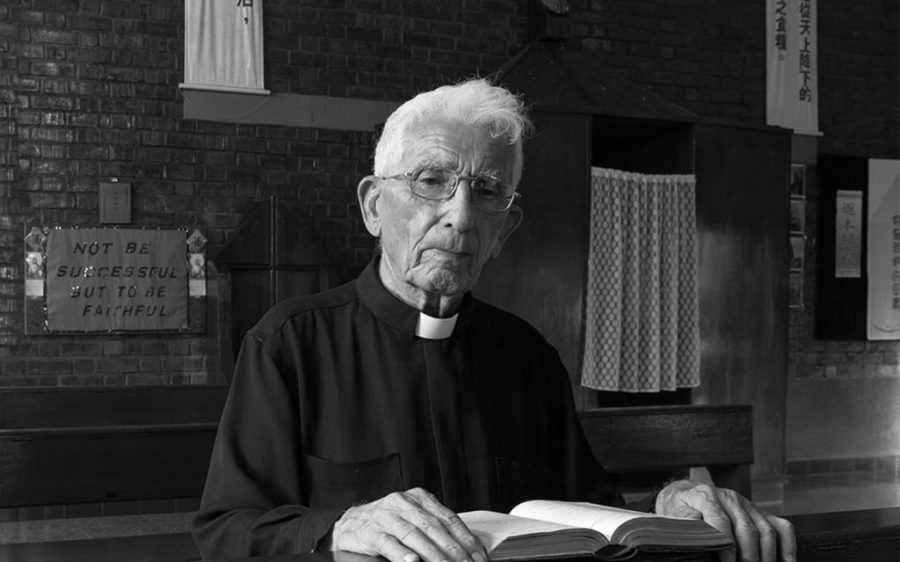

Father Gaetano Nicosia: model of a modern saint

Ká Hó’s journey from a dilapidated cluster of shacks for the socially outcast to a thriving village for patients being treated and even cured is certainly more than the story of one man. But, just as how the history of the Europeans’ arrival in China is incomplete without mention of the Portuguese explorer Jorge Álvares, Ká Hó’s evolution is underpinned by the work of Nicosia, an Italian-born Salesian missionary.

Italian priest Father Gianni Criveller remembers Nicosia fondly. “There are some people who are famous, but they are full of themselves,” he told Macao News. “Even among the church, you find people like that.” But Nicosia, despite being something of a local hero, seemed immune to the self‑aggrandising effects of fame. “There was a kind of surprise that we found his life so meaningful and interesting,” Criveller recalls of their first conversation.

Criveller visited Nicosia in 2015, at the assisted living facility where the latter would pass away in 2017. Now, eight years after Nicosia’s death, the Diocese of Macau has opened a Cause of Beatification and Canonisation for the humble priest. If successful, the typically decades-long process could culminate in Nicosia being recognised as a saint in the Roman Catholic tradition.

[See more: A snapshot into 1930s Macao: the photographic legacy of Melville Jacoby]

A Hong Kong-based Italian priest, Father Lanfranco Fedrigotti, oversaw the Salesians of Don Bosco’s China mission from 2012 to 2018. According to Fedrigotti, starting the Cause was something of a foregone conclusion. Nicosia “heroically devoted all his life to the care of Hansenian patients and poor and abandoned children,” he wrote in a statement to Macao News. As such, many who knew Nicosia already believed he had lived his life in a saintly manner, Fedrigotti said.

For Macao, a rare hub of Catholicism in the mostly secular China, having its own entry in the catalogue of saints would be a powerful symbol for the city. “It puts a spotlight on Catholicism in that particular geographic region,” said Rachel McCleary, an economist who studies canonisations at Harvard University. According to McCleary, having an individual reach sainthood would be akin to receiving a stamp of approval from the Holy See. “You’ll have a lot of foreign pilgrims,” she told Macao News.

McCleary believes Nicosia fits the model of a modern saint – in line with those recently canonised by Pope Leo XIV. As a missionary and member of a religious order, Nicosia would make a prototypical candidate if he is able to fulfil the traditional conditions set by the beatification and canonisation process, she said.

[See more: Unveiling hidden histories: American traders’ glimpses into old Macao]

Last month, following official permission from the Vatican in May, Macao’s Bishop Stephen Lee issued an edict calling for information pertinent to Nicosia’s life as part of the first stage of the Cause. To achieve sainthood, witnesses must attest to his performance of two miracles, which usually take the form of healings deemed medically inexplicable. Nicosia would then need to be judged virtuous by the Congregation of the Causes of Saints.

Passing all stages of beatification and canonisation would take a person who, in the words of one of Nossa Senhora Village’s former residents, turned hell into heaven.

Building hope for Hansenian patients

A fact belied by his documented fluency in Cantonese, Gaetano Nicosia was born in San Giovanni la Punta, a municipality on the Italian island of Sicily. The year of his birth, 1915, coincided with Italy joining World War I, which sent Nicosia’s father to the trenches. Nicosia lost his father to the conflict at the age of three, just a few months before the signing of the Treaty of Versailles.

As a child, Nicosia already exhibited the compassion that his later acquaintances would characterise as a defining trait. According to his own writings about his childhood, he would give half of his breakfast – a piece of bread – to boys in need on his way to school. “He was hungrier than me,” Nicosia reflected in Brief Notes on My Life, a prepublication account of his life that Macao News reviewed.

Nicosia’s desire to serve in Hansenian colonies was sparked at the age of 11, when he saw an image of a patient in the Gioventù Missionaria (Missionary Youth) magazine. “I looked at that figure, I was afraid of it, I turned the page so as not to see it,” Nicosia recalled in his writing. Upon a second glance, however, he was moved by the patient’s face.

“I kissed him and said, ‘In the future I’ll serve you,’” wrote Nicosia. “That figure, that brother, that promise stayed with me all my life.”

[See more: Diving into Macao’s past with João Botas, the history blogger behind Macau Antigo]

Following his training to become a missionary in Italy and then in Hong Kong, Nicosia started work at Ká Hó in 1963.

“In front of Macao, there was a forgotten island where the Hansenian patients lived,” Nicosia later recalled in the 2015 documentary Father Nicosia, the Angel of the Lepers. He described the village as completely isolated: nobody dared enter, and even those who had recovered from their disease were not permitted to exit. In short, getting sent to Ká Hó was a life sentence. Nicosia remembers in the documentary that at least one resident committed suicide by jumping off the cliffs, into the ocean.

At the first meeting he called at the village, Nicosia set some ground rules. First, he changed Ká Hó’s full name from ‘leprosarium’ to Nossa Senhora Village (Our Lady’s Village in English). Second, villagers would refer to each other as brother and sister, instead of being defined by their disease. Third, these brothers and sisters would live normal lives – celebrating holidays, holding meetings and holding elections. Fourth, those who had recovered would be given the option to leave.

‘Working more and better’

At the newly renamed Nossa Senhora Village, Nicosia got to work. He built sturdy new houses to replace the villagers’ makeshift shacks; he bought a generator to produce electricity; he even established a farm with livestock and crops.

According to Fan Kan Shing, a former resident, Nicosia gave villagers a sense of purpose by encouraging them to work and participate in the settlement’s daily activities. Nicosia busied himself with tasks as well: villagers knew him as Sou Dei San Fu (the sweeping priest) for his dedication to maintaining the grounds. Nicosia himself alluded to this title in a letter to his brother Salvatore after receiving the Macao government’s Medalha de Mérito Altruístico (Medal of Altruistic Merit) in 2010.

“They had knighted me, or something like that, for social work, education, instruction, charity,” he wrote. “For me, the most merited award is that of ‘street sweeper’.”

[See more: Three inspiring women from history who have made their mark on Macao]

True to the educational mission of the Salesians, Nicosia also constructed schools in Nossa Senhora Village. The classrooms he built were originally no more than metal-sheet buildings, local docent Anna Leong told nonprofit Fountain of Love and Life. These rudimentary schools have since expanded to become Escola de São José de Ká-Hó and Escola D. Luis Versiglia – institutions that are still active, decades later.

To broaden access to education, anyone who applied to these schools was accepted, and those without the financial means could attend for free. The parent “entrusts this little one to you so that you can look after him… this was the principle in accepting pupils,” Nicosia wrote in Brief Notes.

By 1992, multi-drug therapy for Hansen’s disease had been discovered and most of Nossa Senhora Village’s patients had recovered. This led the Macao government to move the remaining residents into an assisted living facility (Lar de Cuidados de Ká Hó). But Nicosia, despite his advanced age of 75, was determined to continue his mission. “It is a pity that there is afloat this stupid idea that after you are 70 you are useless,” he wrote in a letter to his brother Salvatore and nephew Antonio. “I am now working more and better than when I was 20 years old.”

So, Nicosia began embarking upon monthly visits to some of the last remaining Hansenian villages in mainland China, delivering medication with a team of volunteers. “The doctors were happy because we brought medicines, the sick were even happier,” he wrote of his experience in Ya Xi, Guangdong province.

Nicosia continued living in Nossa Senhora Village and engaging in Christian community activities until a fall in 2010 resulted in a thigh injury. Afterwards, he relocated to Hong Kong and lived primarily in St Mary’s Home for the Aged of the Little Sisters of the Poor in Aberdeen.

That’s where Criveller visited him in 2015, to assist in the production of the aforementioned short documentary. In it, Nicosia appears far younger than his 100 years, talking with his whole body as he describes key events in his life. At some moments, he leans in closer to the camera, eyes glimmering with humour as he shares a particularly memorable anecdote; at others, he gesticulates wildly, with the energy of a man who, not too long ago, was sweeping the streets of the village he transformed.

[See more: City of the Name of God: A guide to Catholic Macao]

Nicosia died in 2017, aged 102, in St Mary’s Home for the Aged. In his final hours, he was surrounded by dozens of fellow clergymen and well-wishers, including close friend Cardinal Joseph Zen of Hong Kong. He was buried at Macao’s St Michael the Archangel Cemetery after a well-attended funeral mass, as reported by local Catholic newspaper O Clarim.

At his vigil, vicar general Pedro Chong described Nicosia’s life’s work as an endeavour to “satisfy the needs of the Hansenian sick, the handicapped, the abandoned and the lost.”

“In Father Gaetano Nicosia, people could see God,” he said.