Today is International Women’s Day. Since it was first observed in 1911, the day has been a celebration of the achievements of women in every sphere. It also marks a call to action for accelerating women’s equality.

The role played by women in the development of Macao has been fundamental if not always acknowledged. The contribution of women everywhere is often excluded from collective memory. But sometimes remarkable women arise from the pages of male-dominated history on the strength of their courage, talent of brilliance. Here are three – and while acknowledging their contribution, we also pay tribute to all women, the unsung heroes, who have made Macao what it is today.

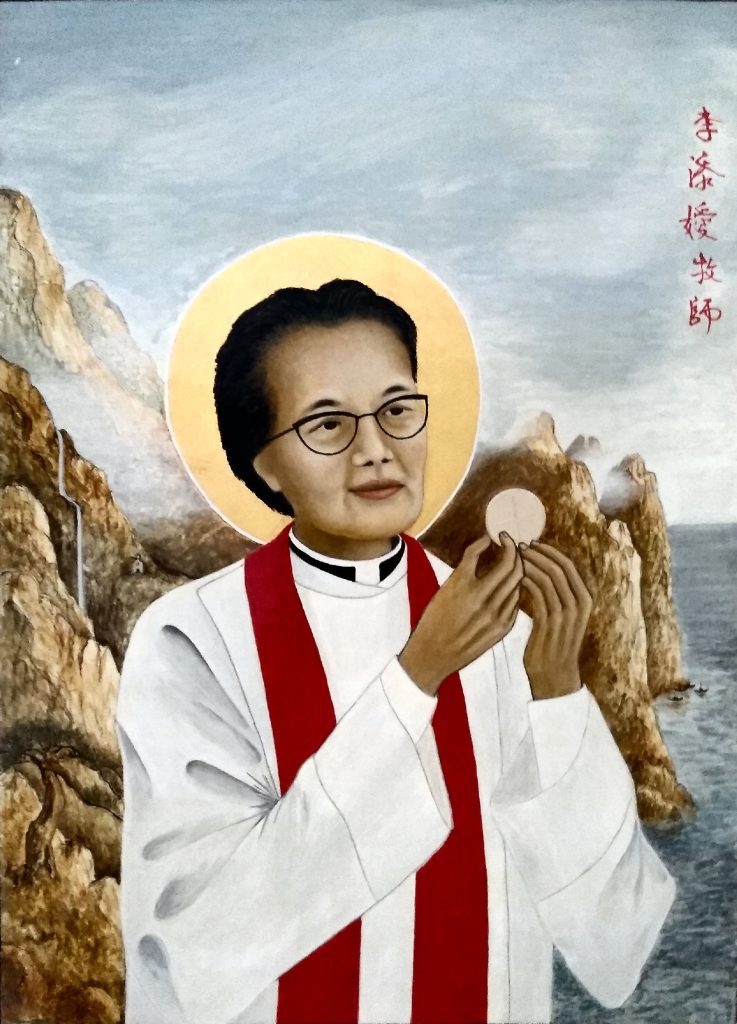

Reverend Dr Florence Li Tim Oi, priest, 1907-1992

Who was she? Born in Hong Kong in 1907, Florence Li Tim Oi was the first woman ordained as a priest by the Anglican Church – which came about as a direct result of her diligent ministering in Macao during the refugee crisis of World War II. Li grew up in a humble family, initially pursuing a career in teaching. But she felt called to study theology, so quit her job and travelled to Guangzhou to do so.

Li lived through Japan’s occupation of both southern China and Hong Kong. The region’s Anglican Church was experiencing its own internal crisis during this time: clergymen from Western countries at war with Japan were forced into detention camps, while Chinese clergymen were conscripted into the military.

And yet, Macao was awash with refugees that its government did not have the resources to support. Starvation and disease were rampant. Churches and civilian groups had to pick up the slack – feeding the hungry, sheltering the homeless and tending the sick.

Enter Li. As a woman, she did not have to fight. That fact, along with her bravery and unshakable Christian faith lead the Bishop Ronald Hall of Hong Kong to dispatch her to Macao. He felt she was the best person for the job. From Macao, Li described the humanitarian emergency in letters. “I found myself behind the men who had the job of picking up the bodies and putting them into a big wooden box-cart to take them to the [mass] grave,” she wrote. They packed them on top of each other like sardines.”

[See more: Meet the women fighting for a better deal for their fellow domestic helpers]

Observing her work, the bishop praised Li as a “quiet, competent and sympathetic pastor”. In 1944, he granted her the official title of priest, believing that “the Holy Spirit had already ordained” her. However, within three years her priesthood was revoked. The Anglican church’s higher ups refused to allow women priests and had threatened to defrock Bishop Hall over his rogue decision.

For Li, the title was irrelevant. She relocated to the mainland in 1947 and continued serving humanity through the church. But life was about to – again – get very difficult. Li was in China during the Great Leap Forward and Cultural Revolution, when Bibles were burned and Christians were subjected to thought-reform camps and imprisonment. She had no idea that the Anglican church finally did start allowing women to be ordained in the early 1970s, and even reinstated Li’s own priesthood.

Li was able to escape China for Hong Kong in 1981. The following year, she joined her family in Canada and went on to become a highly celebrated priest within the Anglican church. In 1984, to mark the 40th anniversary of her original ordination, Li travelled to Westminster Abbey – the mother church – in London and met the Archbishop of Canterbury in person.

Li made her mark on Macao through her tireless work with its refugees and residents during World War II, and in its immediate aftermath. She was at the coal face, and stories of her unfailing kindness later emerged through the accounts of those she helped throughout that nightmarish period.

Why was she inspiring? Not only was Li a demonstrably good human, she inspired the bishop of a 400-year-old, male-dominated branch of Christianity to bestow upon her a ranking never before received by a woman: priest. By all accounts, Li continued to weather crisis after crisis with remarkable compassion and poise.

What happened to her? Li passed away in 1992, in Canada. Afterwards, Canada’s Archbishop Ted Scott described her as having “the resources to forgive all that had been done to her.” The Li Tim Oi Foundation was created in Li’s name to help women in the developing world achieve leadership positions within the Anglican Church.

Harriet Low, diarist, 1809-1877

Who was she? Harriet Low was born into a well-to-do Massachusetts family in 1809 and, in 1829, accompanied her aunt and uncle to Asia. The latter was to conduct business in Canton (off limits to foreign women at the time) and Low was to keep her aunt company in nearby Macao.

Throughout the four years she lived here, Low chronicled her experiences in the forms of diaries and letters. Her introspective, often acerbic writing captured the zeitgeist – at least, for a middle-class segment of Anglo-American society living in Macao in the early 1830s.

[See more: Three local chambers of commerce join forces for International Women’s Day]

There were parties and painting, problems with the city’s Portuguese administrators (of whom Low was entirely dismissive) and cross-cultural comparisons (Low argues, for instance, that corsets were less tortuous for western women than foot-binding was for Chinese). And there were men, who would dash off to Macao whenever their business in men-only Canton would allow: “They seem as though they were just let loose from a cage … all life and spirits,” Low described.

Hardly a wallflower, Low threw herself into the “fancy balls, dances, teas and dinner” of expatriate life. She befriended the surgeon who established China’s first Western-style hospital, in Macao, and the renowned English painter George Chinnery, who painted her portrait. According to her diary, Low “gained a world of experience” while living in the territory.

Low made her mark on Macao by leaving an intimate account of one of its liveliest historical periods. She documented the movers and shakers of the day, and shone a light on Macao’s complex political landscape. Her first-hand, in-the-moment account of life in Macao is valuable for its candour and vivid detail.

Why was she inspiring? For a lady of her station in that era, Low pushed boundaries. She travelled halfway around the world as a young, unmarried woman at a time when that was almost unheard of (Low was the only single woman in her circles in Macao). She also relished the opportunities travel provided: “Everyone ought to go to sea, for they know nothing of the glories of creation until they do,” she wrote. Insatiably curious about Canton, she disguised herself as a boy in order to visit it – and sparked a diplomatic furore.

Perhaps most inspiringly, Low openly grappled with societal prejudices of the day. She expresses a wish to see the Chinese “exalted” and notes that “ignorance must give place to knowledge.”

What happened to her? Low returned to the US in 1834, got married and raised a family. She died in 1877, but the diary of her time in Macao lives on as part of the Low-Mills collection in the US Library of Congress. Low’s daughter published an abridged version of the diaries in 1900, and her granddaughter published a second version that also contained letters in 1953. It wasn’t until 2002 that Low’s journal was published in its entirety, titled Lights and Shadows of a Macao Life: The journal of Harriett Low, travelling spinster.

Marta da Silva, benefactress, 1766-1828

Who was she? Marta da Silva started out as a foundling. Abandoned by her presumably Chinese mother (Silva is often described as having “asiatic features”) and saved from Macao’s streets by nuns, she grew up at the Holy House of Mercy.

But Silva’s lowly birth did not stop her from becoming an incredibly wealthy woman and benefactress. Historical sources indicate Silva was the concubine of a British man high up in the East India Company, Tomas Kuyck van Mierop, and eventually his de facto wife. He left her his fortune, which she – in turn – bequeathed to a whole host of charitable causes, including the Catholic institution that raised her.

[See more: The untold story of the 1971 women’s World Cup is the subject of a new film]

You can still see her full-length portrait hanging at the Holy House of Mercy; an honour that indicates the size of her contribution to the centuries-old institution.

Unlike Harriet Low, whose intimate writing transports readers into the minutiae of her day-to-day life, Silva remains a rather mysterious figure. The British author Austin Coates was so intrigued by the possibilities behind Silva’s trajectory that he centred a novel about her, loosely based on what facts he could find. Coates’ fictionalised account of Silva’s ascent from poverty through finding love is titled City of Broken Promises (1959).

Low made her mark on Macao through her philanthropy. She left enormous sums of money to a number of good causes, including her first home – the Holy House of Mercy – and a school run by nuns. The impact that funding would have had on these institutions’ ability to help the needy was incalculable.

Why is she inspiring? Silva could easily have put her past behind her and lived a lavish life. Instead, she chose to invest in institutions dedicated to helping Macao’s least fortunate – knowing first-hand the impact they had on young lives.

What happened to her? Silva died in Macao in 1828, 33 years after inheriting van Mierop’s fortune.