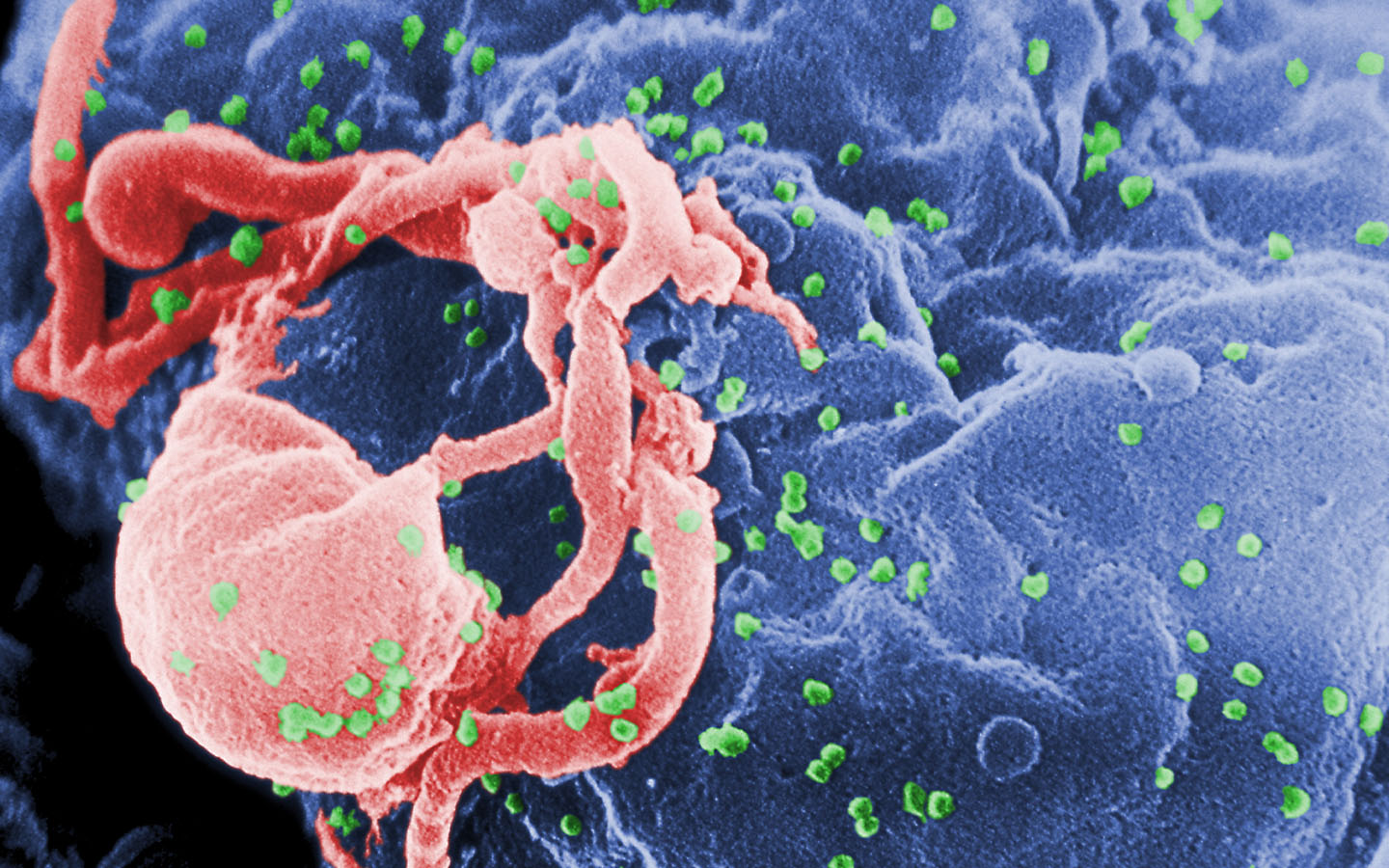

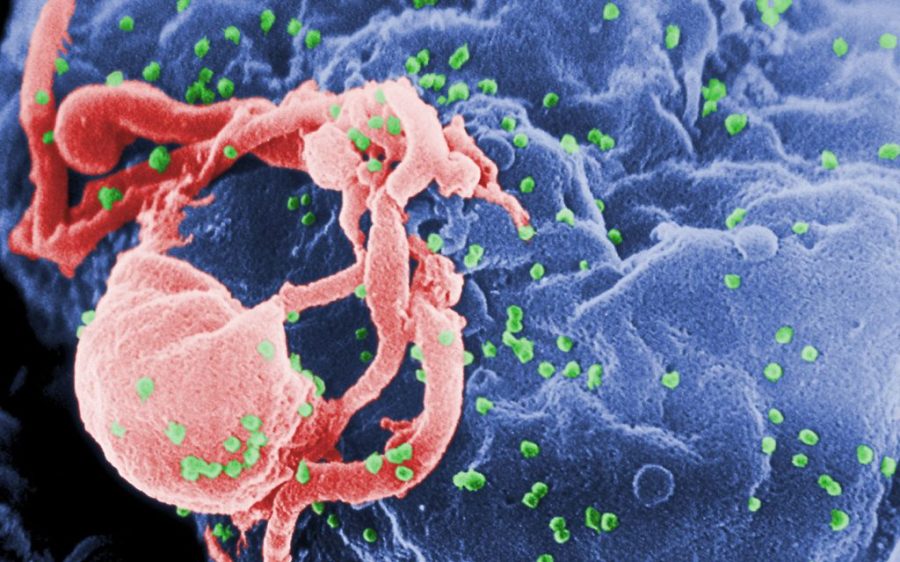

A team of researchers in Melbourne has developed a method to make HIV visible in white blood cells, possibly opening the door to fully clearing the virus from the body.

Around the world, an estimated 39.9 million people are living with HIV, relying on antiretroviral therapies for the rest of their lives in order to suppress the virus and ensure they don’t transmit it. This is due to the virus’ ability to conceal itself within certain white blood cells, creating a reservoir of HIV in the body that the immune system and medications cannot detect.

However, researchers from the Peter Doherty Institute for Infection and Immunity in Melbourne may have cracked this defence. In a study published in Nature Communications, and cited by the Guardian, they demonstrate how messenger RNA (mRNA) – a molecule in cells that carries codes from the DNA in the nucleus to the sites of protein synthesis – can be used to deliver instructions to the cell to reveal the virus, when wrapped in a newly developed nanoparticle.

The hope is that this breakthrough “could be a new pathway to an HIV cure,” explained Dr Paula Cevaal, research fellow at the Doherty Institute and co-first author of the study.

It had long been “thought impossible” to use mRNA in this way, as the type of white blood cells that harbour HIV do not take up the lipid nanoparticles (LNPs) normally used to deliver mRNA. The team developed a new form of this tiny fat bubble, dubbed LNP X, that was able to enter the cells donated by HIV patients. Cevaal recalled when a colleague first presented the test results at a weekly lab meeting, telling the Guardian they seemed too good to be true.

[See more: Personalised gene editing heals baby in world first]

“We sent her back into the lab to repeat it, and she came back the next week with results that were equally good. So, we had to believe it.”

They repeated the experiment over and over, always with the same result. “We were overwhelmed by how [much of a] night and day difference it was – from not working before, and then all of a sudden it was working. And all of us were just sitting gasping like, ‘wow.’”

Despite the significance of this discovery, more research is needed to determine whether the body’s immune system will be able to deal with the revealed virus or require other therapies to fully eradicate it. There also need to be successful animal tests before beginning testing in humans, first undergoing years of safety testing then efficacy trials.

“In the field of biomedicine, many things eventually don’t make it into the clinic – that is the unfortunate truth. I don’t want to paint a prettier picture than what is the reality,” Cevaal emphasised to the Guardian. “But in terms of specifically the field of HIV cure, we have never seen anything close to as good as what we are seeing, in terms of how well we are able to reveal this virus.”