For Macao, 2017’s Typhoon Hato was a reckoning. The storm was the strongest to hit the city in over half a century, and few were fully prepared for the devastation it would cause.

In the space of five terrifying days, Macao faced its highest wind speeds since records began. The storm caused at least 12 deaths and over 200 injuries. The maximum storm surge height reached 2.5 metres along the city’s coast and resulted in 2.25 metres of inundation in its downtown area. In response to the backlash over the lack of adequate warning, the Meteorological and Geophysical Bureau’s then-director, Fong Soi-kun, was pressured to resign.

“I think that it was quite clear then, for the entire population, that this was an issue,” said local architect and urban planner Nuno Soares.

[See more: Macao academics discover links between climate change, health and urban planning]

According to environmental nonprofit Earth.org, Macao’s sea levels are predicted to rise 65 centimetres by the year 2100. The city, which experiences abundant rainfall throughout the months of April to October, is highly vulnerable to flash flooding. Although flood management systems already exist, more needs to be done to protect the city, experts say.

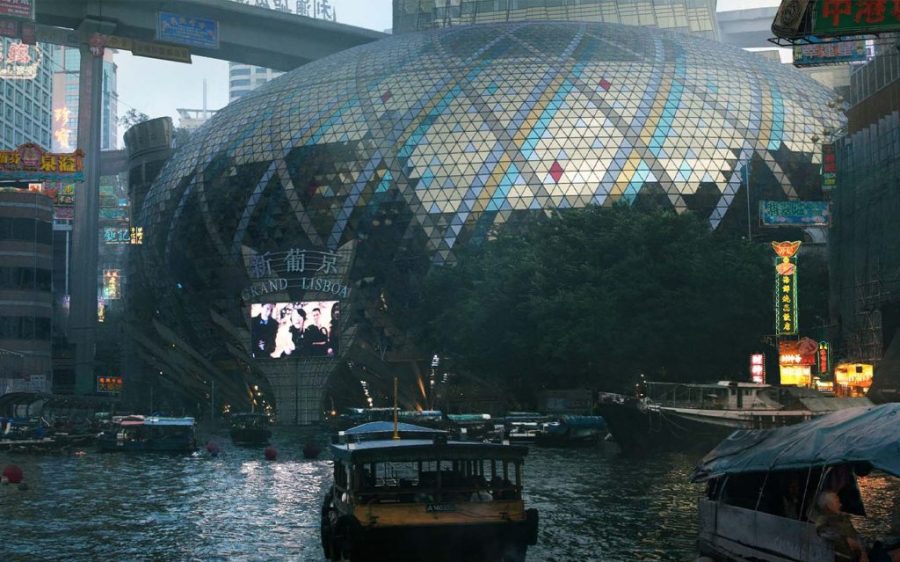

Soares attributes the city’s high risk of flood to the atypical process of its creation. “Macao expanded through reclamations, and it is very close to the sea level,” he told Macao News. The urban planner has done extensive research on the city’s Inner Harbour area, which he says is most susceptible to floods due to its low elevation – a mere 3.2 metres above sea level. In 2013, Soares conducted a thorough survey on the area, culminating in the publication of his book, The Inner Harbour – Policy Recommendations on the Revitalization of Macau’s Vernacular Heritage.

As climate change worsens, Macao civil engineer Gao Liang says the worst is yet to come. “Because of the rise in temperatures, the air can hold more water, so precipitation can be much heavier,” she told Macao News. Additionally, warmer seas can also intensify typhoons, as well as make them harder to predict. “All those factors contribute to exacerbating flood scenarios,” Gao said.

[See more: Climate change: Cities are trying innovative techniques to beat the heat]

Soares, who consults on urban planning projects for the Macao government, says that local authorities have previously considered prevention flood strategies such as dykes (artificial embankments), sea walls and box culverts (structures that channel water under or through an obstacle) – the latter of which is currently in the works. According to the city’s Urban Planning Master Plan 2020-2040, the government also intends to implement flood management systems such as tidal dams, water reservoirs and pumping stations.

Not all of these solutions hold up against more severe storms, however – during typhoons, pumping stations may not be able to operate due to power outages, Gao said.

Even for the ones that do work, “With the sea level rise that has been happening, [Macao] will become more vulnerable,” Soares told Macao News. The problem, he says, “needs to be tackled in a more dramatic way – I think we really need a holistic solution.”

Adopting green solutions to Macao’s flood problem

One possibility? What experts call the “sponge city” model. Environmental scientist Karen Tagulao of the University of Saint Joseph, an expert on sponge cities, says a hint is in the name: “Sponge is a material that absorbs water,” she told Macao News, “and that is exactly the concept of a sponge city, but using green infrastructure.”

In highly urbanised places such as Macao, most surfaces are made of concrete or asphalt, both impermeable materials. “Concrete pavements cannot absorb [water]… so the water can rise very quickly,” Tagulao said. A sponge city, however, would make use of layers of substrate in order to allow water to infiltrate.

[See more: Paying more for your coffee? Blame climate change for that]

Tagulao believes such an approach would be highly feasible in Macao. Nature strips on the sides of roads, for example, can be retrofitted to become so-called “rain gardens”, which soak up water instead of letting it flow into storm drains. “When the rain comes, the water can flow into the systems, store the water and then gradually release it,” she said.

Other natural solutions, such as natural “green walls” formed by mangroves, can also help, Tagulao said: “[Mangroves] can help protect the coastline from flooding because of their ability to attenuate waves,” she explained, reducing their amplitude. “So before the waves even enter the city, they will pass through the mangroves, and the height of the waves will already be lower,” she said.

That said, “grey infrastructure” – traditional man-made drainage systems – also plays a part. Gao said that the city could look towards East Asian examples such as Tokyo or Hong Kong as references: both built tunnels that can be opened during heavy floods, storing water.

[See more: Fuelled by climate change, wildfires are sweeping across Europe]

Regardless of which specific solutions end up being implemented, however, Soares believes there’s more to be done.

“We’re dealing with human lives; we’re dealing with property; we’re dealing with this feeling of vulnerability that makes people feel uncomfortable and lose confidence in the future development of a place,” he said. “It’s something that cannot be overlooked.”