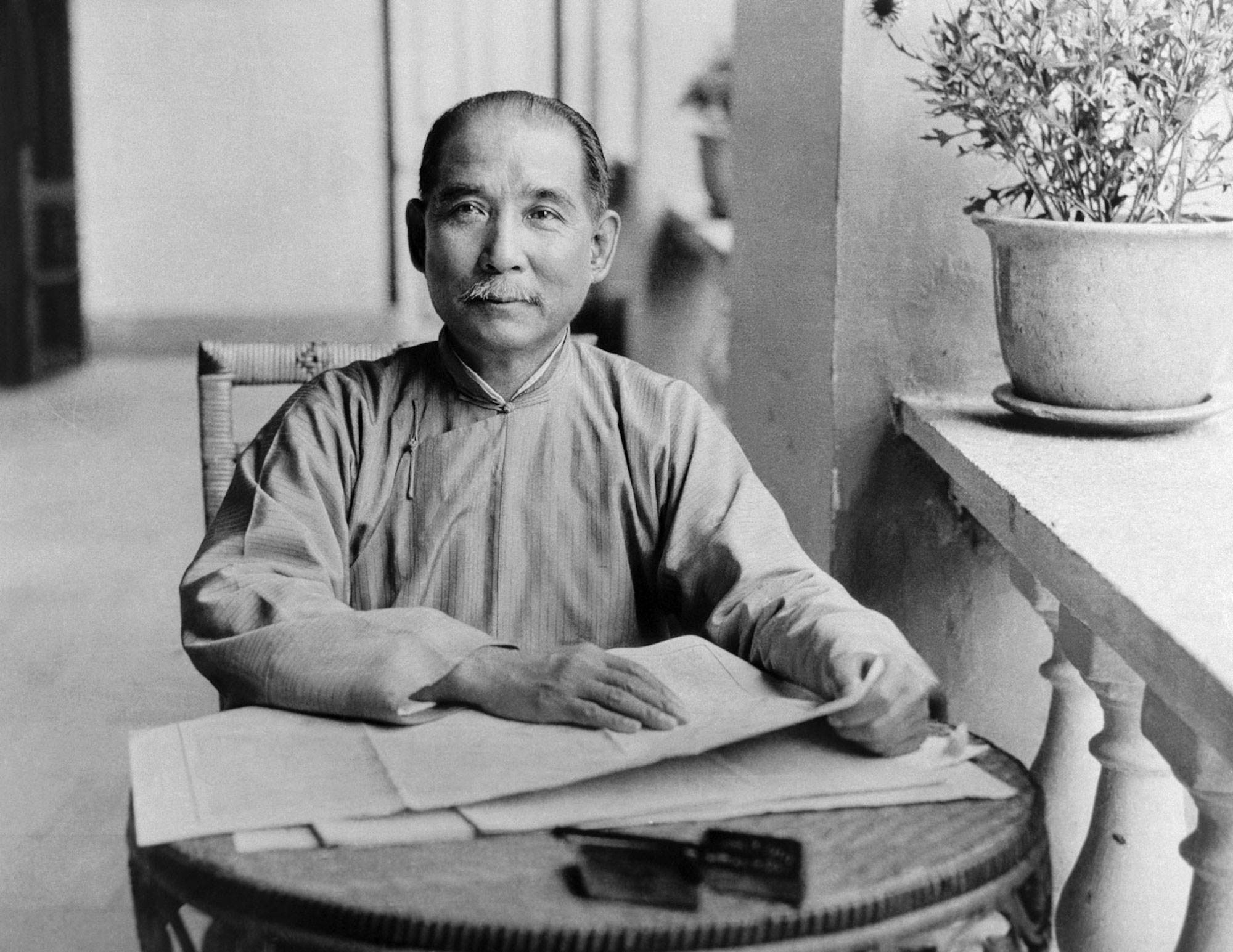

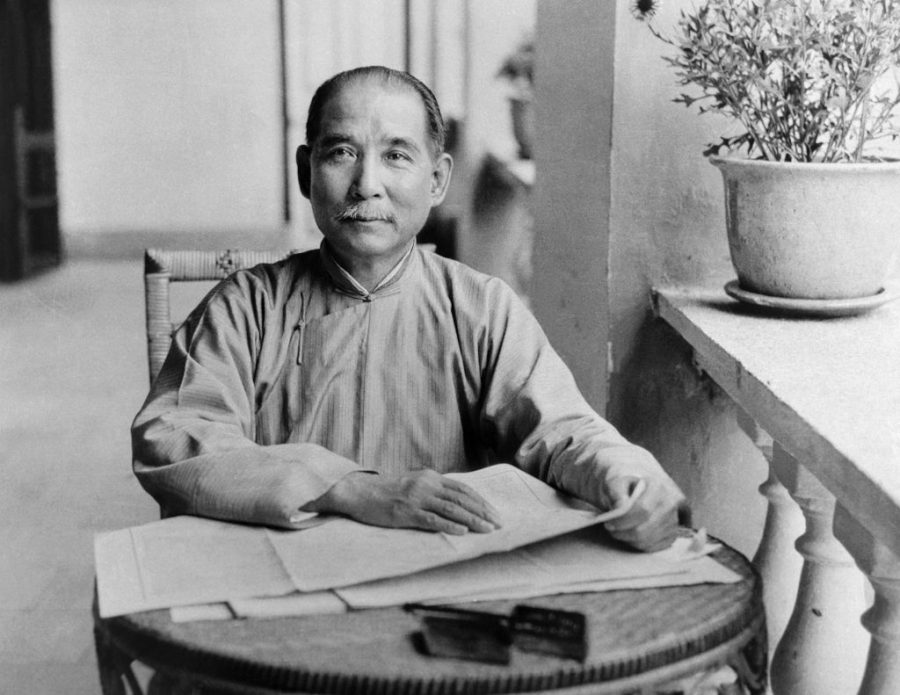

Sun Yat-sen is known around the world as the father of modern China, the man who ignited the revolution that overturned 2,000 years of imperial rule and established Asia’s first democratic republic. Less known about him is the role that Macao played in his life.

It was the city where his father worked for many years, where he started his medical practice – and where his journey nearly came to a screeching halt following a failed uprising. It was also the city where his family lived for many years after the revolution in mainland China.

“The experience of living in Hong Kong and Macao was critical to Sun’s thinking,” said Ye Chun, a historian in Hong Kong. “A man from rural China saw two societies that were orderly and well managed. It made him ask why the Chinese could not run their own affairs.”

But the city was more than just the place that opened Sun’s eyes to new possibilities. For many years, Macao was home. Even today, his history lives on in monuments and museums, a symbol of national pride.

Humble beginnings

In 1849, Sun’s father, Sun Dacheng, came to Macao, where he worked in a shoe shop for 16 years before returning to his hometown, the village of Cuiheng in Guangdong province, just 37 kilometres north. There, he began to work on a farm and married a woman known simply as Madame Yang. On 12 November 1866, the two welcomed their son into the world: Sun Yat-sen.

In 1879, mother and son passed through Macao on their way to Hong Kong, where they took a British steamship bound for Hawaii. In Hawaii, Sun lived with his older brother, learned English and studied at secondary school until 1885, when he returned to his humble hometown to marry Lu Mu-zhen, the daughter of a Chinese merchant in Hawaii. Like many marriages at the time, theirs was arranged by the two families.

Sun’s itinerant early life continued after that, when he moved to Hong Kong to study at what is now the Diocesan Boys’ School, one of the most famous in the then colony, and then Queen’s College. His outstanding exam results enabled him to study medicine at what became the medical school of Hong Kong University. When he graduated in 1892, the young talent became one of the school’s first two Chinese graduates.

He also began to adopt new views. Against his brother’s objections, Sun converted to Christianity while living in Hong Kong, and during his frequent trips to Macao, he began to envision a new path forward for China.

Leaving the practice to lead the revolution

In September 1892, Sun moved to Macao, where he took a job at Kiang Wu Hospital, the first non-profit hospital established by and for Chinese, and became the first Chinese person in the city to practise Western medicine.

The hospital gave Sun a loan of MOP 1,440 to open two clinics, one at 80 Rua das Estalagens, where he could offer both Western and Chinese medicine. But he didn’t just keep busy with his medical work. He also continued the revolutionary activities he had begun in Hong Kong.

While Sun was living in Hong Kong, he held meetings and wrote tracts against the decay and corruption of the Qing government. He had also made friends with a Portuguese printer and translator at the Hong Kong High Court named Francisco Hermenegildo Fernandes, who was sympathetic to his ideas.

In 1892, Fernandes returned to Macao and founded the Portuguese-Chinese Echo Macanese newspaper. In his upstart paper, Fernandes often ran articles by and about Sun, despite their sensitive nature, publishing stories promoting political reforms as well as news of his medical work. Sun’s words soon reached readers in Xiangshan, Guangzhou, Hong Kong, Fuzhou and Xiamen in addition to Macao.

While Sun was a dutiful doctor, his greater mission in life was to reform China. In the 1890s, he wrote a long article to Li Hong-zhang, one of the highest officials of the Qing government and a leader of the “Self-Strengthening Movement”, which aimed to modernise the country. The articles set out the reforms Sun considered necessary to change China and confront Western powers. Li did not dignify him with a response. For Sun, that moment solidified a belief that had been forming in his mind: since the government was unwilling to reform, violent revolution was the only way forward.

Sun realised his mission in life was not to treat the sick, but rather to treat their minds, and so he closed his practice in Macao in September 1893 to focus on the revolution to come. However, powerful people were watching in the Qing government.

In October 1895, Sun and his compatriots incited an uprising in Guangzhou. The revolution was doomed from the start. News of it was leaked to the government before it took place. Sun soon found himself on a wanted list, and the Hong Kong government banned him from entering the city.

Fernandes stepped up. He hid Sun and then leveraged connections to smuggle him out of Macao by boat, first to Hong Kong and then Japan. Sun would spend the next 17 years in exile, but he never forgot his friend. As a token of gratitude for saving his life, Sun would later give Fernandes his medical equipment and daily items, now on display at the Dr Sun Yat-sen Memorial House in Macao.

An everlasting legacy in Macao

After numerous failed uprisings, Sun’s band of revolutionaries finally succeeded when a Qing army rebelled in Wuhan on 10 October 1911, leading to the overthrow of the Qing dynasty. Sun was named provisional president of the Republic of China, but he held the post for only three months before conceding the position to Yuan Shi-kai, the most powerful warlord in China, in April 1912.

After the revolution, Sun returned to Macao only twice. In May 1912, he visited friends and supporters at the invitation of prominent Chinese businessmen. He was hosted by Lou Lim Ioc at his home in what was then called Yiu Yuen – what today is the Lou Lim Ioc Park. In 1913, he returned for a final time to see his daughter and meet the revolutionary Chen Jiong-ming.

While Sun himself had little contact with Macao after the revolution, the city was of great importance to him as the home of his family. With his wife, he had one son and two daughters, and in 1913, the three moved to Macao with Sun’s brother Sun Mei. Just two years later, Sun would divorce his wife Lu and marry his secretary Soong Ching-ling. After the marriage, Sun bought a house in Macao for his now estranged wife Lu and the children.

Lu continued to live in this house with her three children and grandchildren, but in 1930, an explosion at a nearby army munitions warehouse destroyed it. Deeply embarrassed, the government provided the family money to build a new three-storey structure, a gift that was supplemented by money from her son and Sun’s brother in Hawaii. With this capital, the family built the spacious three-storey structure – a home boasting a decidedly Western aesthetic, with wooden floors, large wooden furniture and big wardrobes – that visitors can find in Macao today.

In 1958, the building was restored and named the Sun Yat-sen Memorial House. It has since become one of the most popular attractions in Macao for visitors. In the courtyard sits a full-length bronze statue of Sun, cast by his Japanese friend Umeya Shokichi in 1934. Inside, photographs speckled throughout the museum evoke the memories of Sun’s extraordinary life – including memories of his journey across Asia, Europe and the United States in search of support and funds. They show the images of the new republic, with Sun and the other ministers, full of hope and optimism.

More than Sun’s keepsakes live on in Macao, though. The city has recognised this important historical figure with a park – the largest in the city – two roads and a memorial hall named after him. Three statues of him can be found in Macao, including one in the courtyard of Kiang Wu Hospital. And in 2016, one of Sun’s original medical clinics was painstakingly restored. Located on 80 Rua das Estalagens, this latest addition to Sun’s legacy includes an exhibition on his life, as well as a look back at the space in which a young doctor helped to change local views toward Western medicine – and cultivate his own radical views on governance in his native land.

Close to a century after he died of liver cancer in Beijing in 1925 at only 59 years old, Sun retains an enormous prestige among the Chinese people, both at home and abroad. He is one of the few political leaders respected by both the Communist and Nationalist parties and a symbol of unity between them. Both refer to him as “Guofu”: Father of the Nation. His odysseys around the world, his command of English and an intense curiosity enabled him to learn many of the best values of the countries he visited and incorporate them into the Three Principles of the People – nationalism, the people’s power and the people’s livelihood, his guiding ideology for the future of China.

All of this history quietly lives on in Macao, one of the most important stops in Sun’s itinerant journey in life. It’s an unmissable destination for those looking to retrace the steps of the father of the Chinese revolution.