After a long day of teaching, Oscar Munoz Balajadia Jr., 53, sits beside me in the dimly lit courtyard of his apartment building where his Chinese wife, Lei Kam Sio, is still busy tutoring students. Then he produces a can of cider from his backpack and hands it to me with the hospitality that Filipinos are famous for.

Despite his conviviality, Balajadia is an outlier when it comes to his compatriots in Macao. “I just don’t know the [Philippine] community,” he says, attributing that to his passion for creativity. “I’m married to my writing and to my art.”

As a friend to Balajadia for almost a decade, I can vouch for that. Since 2004, he has held five solo art exhibitions in the SAR, in addition to participating in many group exhibitions. On top of that, he is constantly producing visual and literary works, which he publishes online and in book form.

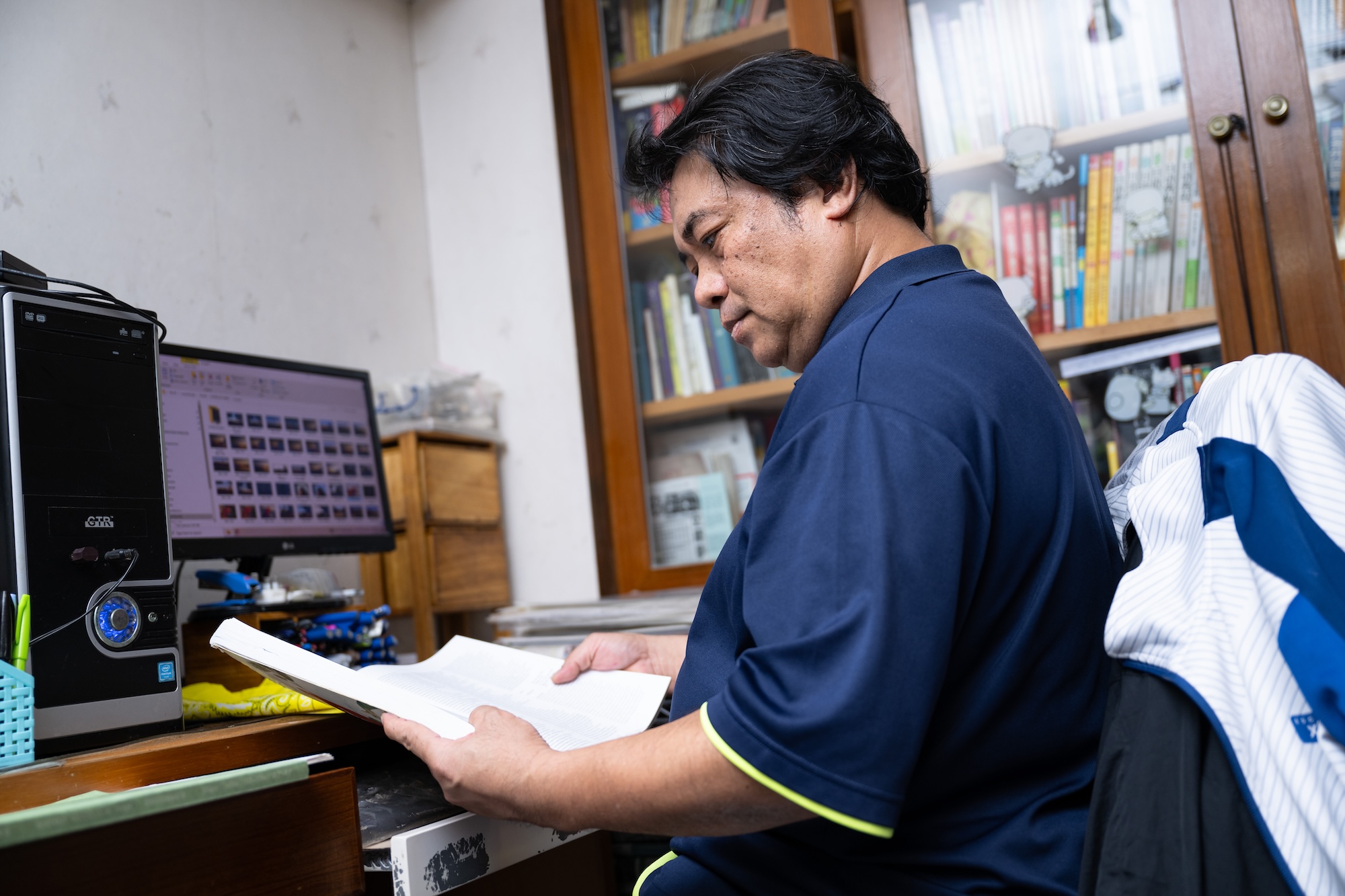

“I am simultaneously preparing manuscripts of etymology books, dictionaries, poetry, and collections of artworks,” Balajadia tells me. He also happens to be an English teacher, a linguist, musician, an amateur historian, and a YouTuber. To put it simply, he is a polymath, although he refuses to label himself as such.

The language of learning

Born in the Philippines in 1970, Balajadia was the middle child in a large family of five children. “I was a sickly kid who was not out a lot. And I was always with my mum,” he remembers.

The time that he spent indoors sparked his love affair with poetry. “The first poem that I heard from any person was from my mum,” Balajadia recalls. “She was reciting Joyce Kilmer and that poem stayed with me. From then on, I said to myself, ‘I could be a poet.’” He also attributes his interest in visual art to his mother, saying that she “was doing embroidery and that inspired me a lot.”

Balajadia graduated from the Catholic Holy Angel University (HAU) with a bachelor’s degree in literature in 1993, publishing a collection of verse while still an undergraduate. Intending to become a priest, he enrolled in the Comboni Missionary seminary.

His superiors planned for him to study theology in Portugal, and to prepare him for that sent him to Macao – then still a Portuguese-run territory – so that he could familiarise himself with Lusitanian culture. Balajadia worked under the first Chinese Bishop of Macao, Domingos Lam, in the Cathedral library and assisted the nuns who ran the diocese’s Cineteatro Cinema. But he came to realise that the priestly life was not for him and parted ways with the church.

To support himself, he found work at the Livraria São Paulo bookstore and it was there that he met the woman who would become his wife. It was an encounter that changed everything, for as the relationship deepened Balajadia realised he would now be making Macao his permanent home.

He also found his calling in education. Over the past 20 years, Balajadia has had a long and varied teaching career, having worked at Colégio Diocesano de Sāo José 5, the International School of Macao, Hou Kong Middle School, and Macau Anglican College. At present, he teaches English to primary school students at Escola Xin Hua.

Another great love is the culture of his home province in the Philippines, Pampanga. He has written two large volumes on the etymology of the endangered Kapampangan language. The first – at 950 pages – won him the 2017 Philippines National Book Award in the language category. Rather than accept the prize money, Balajadia donated it to his alma mater, with the request that it be used to fund a songwriting contest that would encourage students to write and sing in Kapampangan.

An opening in Macao

While teaching remains one of Balajadia’s lifelong passions, he is also equally drawn to art and poetry, which he produces under the pseudonym of Papa Osmubal. The “Papa” part because of his love of Hemingway (“Hemingway’s nickname was Papa”) and “Osumbal” being a portmanteau of the first syllables of his given name, middle name and surname.

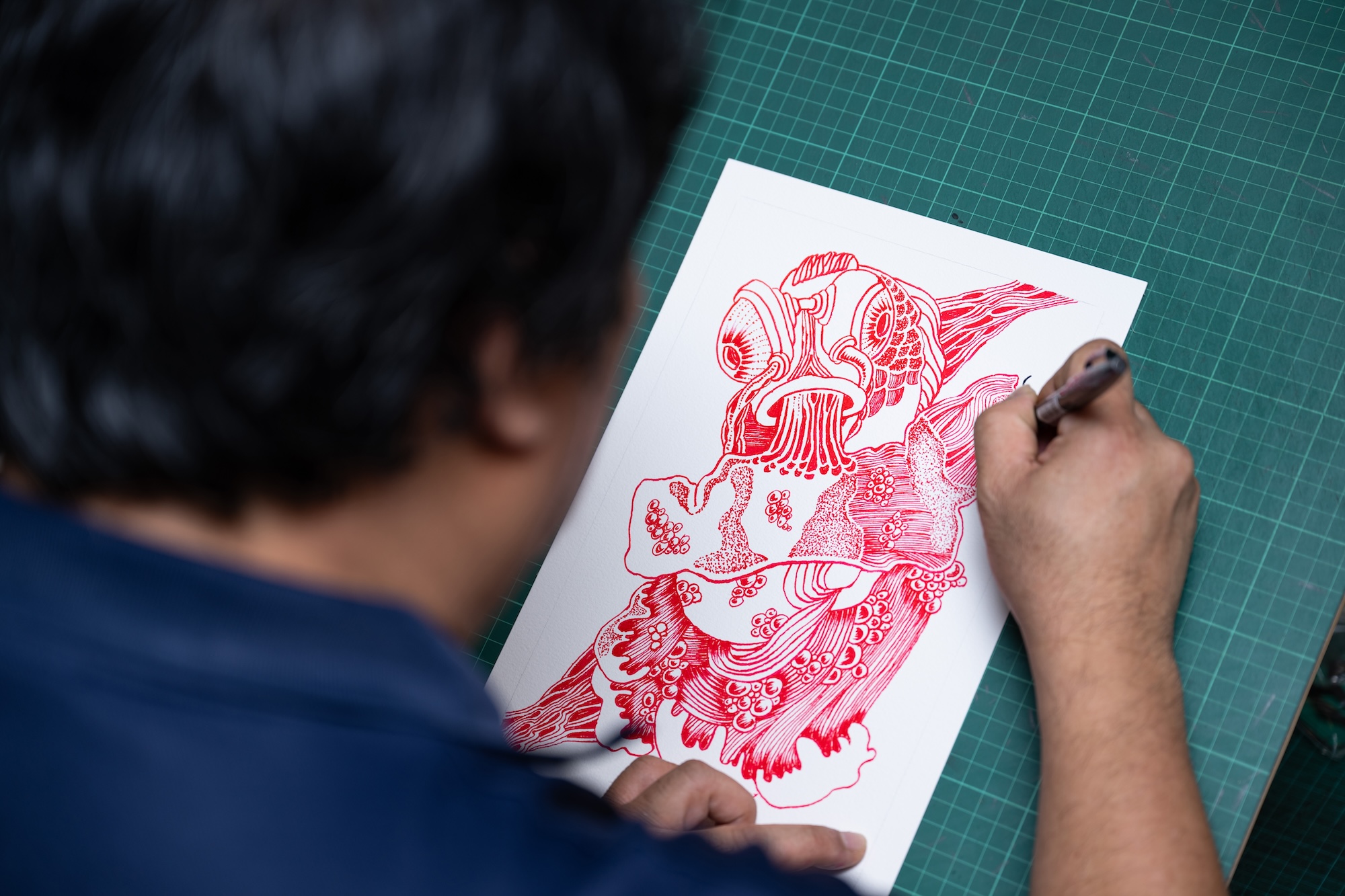

As Papa Osmubal, he held his first solo exhibition in 2004. Entitled White and Black, it showcased his abstract charcoal and ink art pieces. The event, he says, “validated my presence in Macau – it cracked an opening for me.”

Balajadia has since experimented with a range of media. For his 2015 exhibition, Voice in the Murk, he used pen, pencil and ink to create abstract sketches. He presented the major historical landmarks of Macao in the form of intricate paper cuts for his 2016 Voice on Paper exhibition.

He is equally gifted as a poet, having published on numerous platforms. His latest poetry collection, The Only True Eye features many poems inspired by his experience in Macao. “It’s an obligation that you open your eyes to your surroundings,” he says.

Balajadia shows no sign of slowing down anytime soon. “While I’m alive,” he says, “I have to work more.”

At present, he is compiling an encyclopaedia of the history of Macao, with short entries related to its historical sites, early governors, and more. For the past three years, he has been constantly gathering information for the book, but is unsure of when and if this long-term project will be completed. Even if it isn’t, the mere fact that Balajadia has committed to such an undertaking is an eloquent love letter to the city that he proudly calls home.