Gonçalo César de Sá had his first journalistic scoop when he was in his early 20s. As a junior reporter at Radio Clube of Mozambique in Lourenço Marques (now Maputo), Mozambique, César de Sá was responsible for calling the fire station, police, hospital, airport and port every morning to inquire about recent incidents.

“I did it every day for months until one day, there was a huge train accident. I was the first person to broadcast about it – it felt great to get the story,” he recalls of the adrenaline rush.

Little did the young reporter know, this would be one of many scoops in his distinguished, colourful career. During the next five decades, he worked in 38 different places, wrote for more than two dozen publications, co-wrote more than a dozen books, produced eight documentaries and founded a leading media group in Macao.

César de Sá, who was born in July 1947 in the Mozambique port city of Lourenço Marques now Maputo, didn’t always want to be a journalist. In fact, he had originally hoped to study architecture, inspired by family friends growing up.

“When I was 18, I had a group of friends whose parents were all architects, such as the Amaral, Pimentel, Tinoco and Brusky families, and others,” he recalls. “They taught me a lot about life, to see beauty in everyday things – their influence was tremendous. So many years have passed, but I still have close friends from that period.”

To fulfil his dream of becoming an architect, César de Sá moved to South Africa after secondary school to study at the University of the Witwatersrand in Johannesburg. University didn’t go quite as planned, however, and César de Sá dropped out about a year later. He was automatically conscripted into the Portuguese Colonial Army in Mozambique.

Times of war

From 1968 to 1972, the young man became a lieutenant and trained other soldiers, then fought in the Portuguese Colonial War – a conflict between Portugal and its African colonies. Between 1970 and 1972, he was posted in Tete, a city located on the Zambezi River, in west-central Mozambique, where he and his platoon were in charge of escorting construction material and professional workers for the Cahora Bassa dam project.

As a lieutenant, he witnessed terrible scenes: “People died. People lost arm and legs. We fought, but we never saw the ‘enemy’ (Mozambique Liberation Front) because it was a guerrilla war, it was very difficult,” he says.

César de Sá felt deep appreciation for the friendship and support from his fellow soldiers during the conflict. “We were all trying to survive together – there was a sense of camaraderie all the time. This is something that I will never forget, it was truly a traumatic experience.”

He returned to journalism almost immediately after leaving the armed service. “I couldn’t become an architect, so I decided to become a journalist since I really loved to write,” he recalls. In 1974, he joined Radio Clube of Mozambique.

One of the most interesting periods of his career occurred soon after. While working in Africa, he covered the Lusaka Accord between Portugal and the Mozambique Liberation Front (known as the FRELIMO), which was signed in the Zambian capital on 7 September 1974. According to the accord, Portugal recognised the right for Mozambique to gain its independence and agreed that Mozambique would become a new nation in June 1975.

“I was there to see the end of Portugal’s history and presence in Mozambique,” he says, recalling the discussions between Samora Machel (who went on to become the first president of Mozambique) and Mário Soares (who would become the Prime Minister of Portugal) in the presence of then-Zambian President Kenneth Kaunda.

Following the historic event, the transitional government of Mozambique recruited César de Sá to work in the Ministry of Information where he met some of the insurgents who he had fought in the war. “They are the ones who took power in Mozambique and the ones I had fought against only two years before – Portugal gave them independence [which ended the war]. It was a very strange experience to work with FRELIMO every day; I had mixed feelings about it, as you can imagine.”

A year later, before Mozambique’s independence, he moved to London to work with the BBC’s Portuguese service, then jumped to Lisbon, Portugal, to join ANOP (the Portuguese News Agency) from 1975 to 1976. It was at ANOP in September 1975 that César de Sá was sent with his colleague Luís Pinheiro de Almeida to cover the Angolan independence ceremony. It was a difficult assignment and, in the end, the government expelled the journalists from Angola, taking issue with the team’s independent reporting style and critical coverage.

Then came his first of many forays in Macao. In 1976, César de Sá moved to the city, which was then under Portuguese administration, to become the press attaché of the Macao governor. At the same time, he became ANOP’s Macao correspondent. “This era in Macao was very beautiful,” he says.

“The city was calm and quiet, there was never any rush to go anywhere. I’m not against modernity, but at that time, we could just sit outside at the Hotel Caravela (which was demolished in the late 70s), sip coffee, watch the junks pass, watch the fishermen with their nets and feel a sense of calm.”

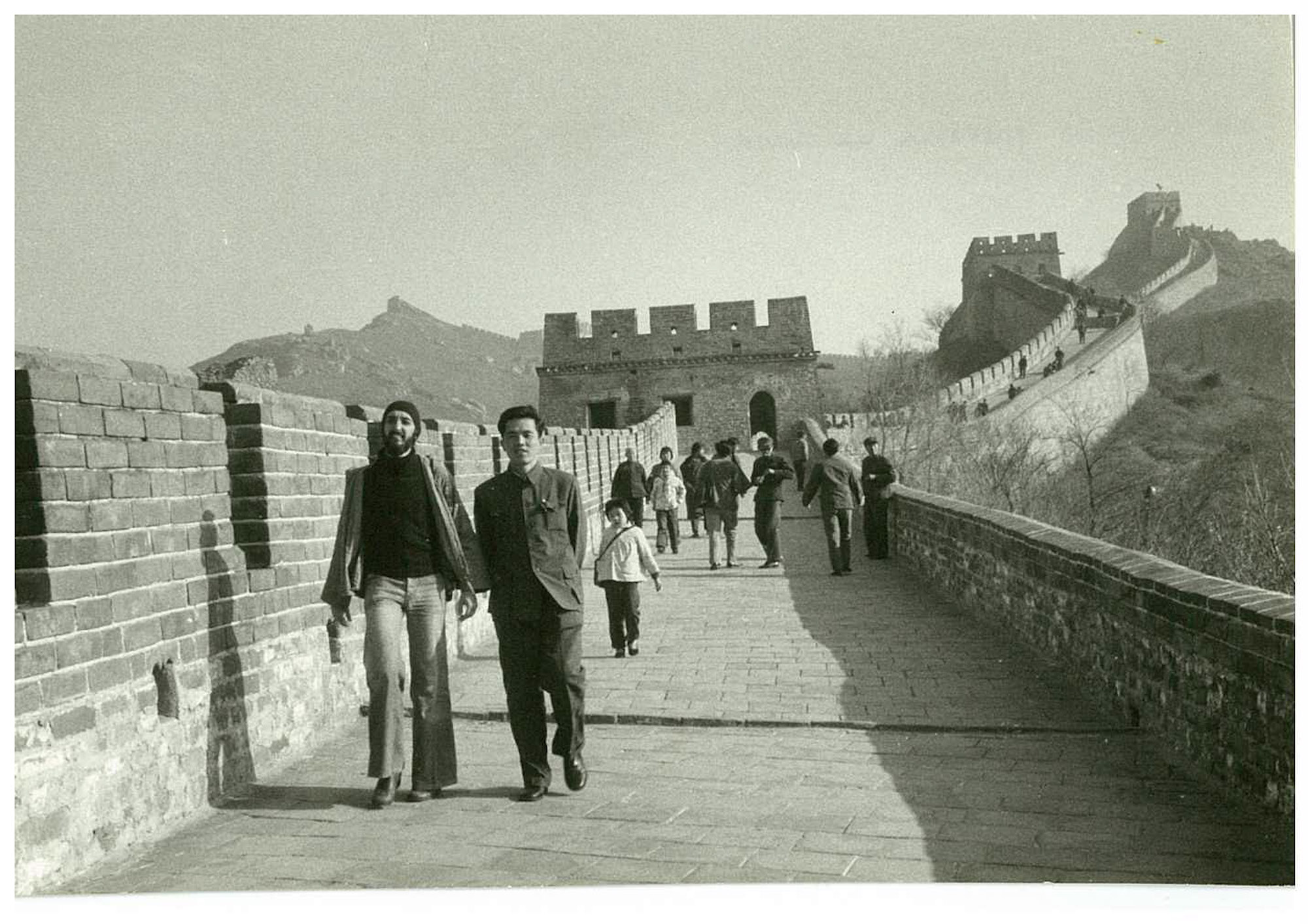

His role with the government led to a major career milestone. At the time, diplomatic relations between Portugal and China did not exist, but negotiations were about to begin. After ANOP invited Xinhua News Agency’s Madrid correspondent to visit Portugal, Xinhua News Agency reciprocated, inviting ANOP’s Macao correspondent – then César de Sá – to visit China in 1978.

“That was my first experience with China,” he says. “It was incredible – everything was grey. No one looked at your eyes. All the conversations were very political.”

The first Portuguese journalist in China

César de Sá spent the next month reporting all over China, visiting the smaller cities as well as far-flung provinces and rural communities. When he returned to Beijing, officials from China’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs called him with the news: diplomatic relations between Portugal and China would begin imminently. In February 1979, People’s Republic of China and the Portuguese Republic signed an accord to establish diplomatic relations.

“I was the first Portuguese journalist to go to China, so I came back to Macao with lots of insights and experiences,” he says. “I am glad to have participated in this period of history.”

With a feather in his cap, César de Sá returned to Macao where he stayed until the end of 1979. He then returned to ANOP in Lisbon before shifting to work at the Portuguese Television (Rádio e Televisão de Portugal). But it wasn’t long before the Macao government asked César de Sá to return with a team and prepare to launch Macau Radio and Television (TDM), where he would take up an exciting role as the news head. From 1980 to 1986, César de Sá honed his executive skills, directing dozens of reporters, producers and radio hosts.

“I need an orchestra to work well – and I like to get involved in everything,” César de Sá says of his role. “Back then, I enjoyed my time at TDM working the radio and television. But, today, I think it is more exciting to work with video and new media. It is the future.”

At the same time, in the early ‘80s, César de Sá also worked as a Macao stringer, or local contributor, for several news outlets in Hong Kong and Portugal, including RTHK, Agence France Presse, the Far East Economic Review and O Jornal. “I was very, very active since no one knew anything about Macao and I was the only one there,” he recalls. “I have always been lucky – the right place, the right time. It is fantastic.”

Almost at the same time, Xinhua News Agency invited César de Sá to go to Beijing to interview China’s then-Vice-Minister of Foreign Affairs Zhou Nan, who was leading the Chinese delegation in talks with Portugal about the future of Macao.

During that visit, Zhou Nan announced that China would start negotiations with Portugal to decide when to begin the transfer of the administration of Macao from Portugal back to China. It was a global story because Portugal did not believe that Macao would follow Hong Kong’s future – and it was César de Sá who broke the news.

In 1984, César de Sá shifted his role to focus on the TDM’s Special Projects division, where he managed a regional TV series on Portugal’s expansion across Asia in the 16th century. Fascinated by these historical developments, César de Sá ultimately co-produced eight films about Portuguese history and influence in Malaysia, Singapore, India, Thailand, Indonesia and Japan for Portuguese Television (RTP) and TDM.

“So for about 2.5 years of my life, I was travelling and filming. I really got to see all of the roots of Portugal in Asia. It was incredible. I never imagined that I would be able to do that.”

Almost as soon as he started his new role, he received a grant from the Japanese Hoso Bunka Foundation to produce several film documentaries about the Portuguese presence in Japan in the 16th century – an opportunity that enabled him to travel to far-flung corners of Japan.

He thrived in this new environment, devouring the culture, food and history of the island nation. “Japan was fabulous. I love the simplicity. I love the fact that you have the old and the new side by side.”

In addition to the films, César de Sá also co-authored two books: Tanegashima: The Island of the Portuguese Gun for the Instituto Cultural de Macau (Cultural Affairs Bureau) and 450 Years in the Relations Between Portugal and Japan for the Portuguese Embassy in Tokyo.

There are so many interesting stories that came out of this research, he says. “One [that stands out] is about the Portuguese and Japanese relationship. The Portuguese were the first westerners to arrive in Japan, on this very small island in the south of Japan called Tanegashima.”

“When the locals saw their guns, they requested a copy. The Portuguese gave them one, but the Japanese didn’t know how to develop the trigger without the gun exploding and killing someone. So they asked a Portuguese officer to teach them how to make it. The man said, sure, but you have to give me your daughter. And they made a trade.”

But what’s most interesting, he adds, is that even 500 years later, the little island still celebrates the day the Portuguese taught the Japanese the mechanics behind a gun’s trigger. Every June, they hold a huge parade, complete with giant floats and Portuguese flags. “For me, learning all about these histories was one of the most interesting periods of my life.”

Working around the world

In 1986, Lusa (the Portuguese News Agency) invited César de Sá to become the regional director of news operations in Asia, with a base on Macao. As the director, he oversaw offices in Hong Kong, Taipei, Beijing and Tokyo and correspondents in Sydney, Bangkok and Seoul.

Continuing his role with Lusa, he moved to Tokyo in 1989 for three years to expand the company’s footprint in the region. Then in 1991, returned to Macao with the same news company where he stayed for the next eight years.

This longer stint in Macao led to another career milestone. Portugal did not have relations with Indonesia, due to disagreements over the sovereignty of Timor-Leste, a Southeast Asian nation that was once a Portuguese colony.

“News agencies usually play an important role in establishing relations, so I thought, ‘Why not try to set up an agreement with the Indonesian news agency and Lusa, the Portuguese News Agency?’ It would be the first step for the relations,” says César de Sá.

In 1998, César de Sá spent five months pushing for a meeting between Lusa and ANTARA, the Indonesian news agency. They finally reached an agreement, which opened the possibility to set up a Lusa office first in Jakarta and later in Dili, Indonesia.

“This helped to share the knowledge between the two countries. It established a point of contact and started the relations between Lisbon and Jakarta, which happened a year later. So I had some part in that process,” he recalls.

His work to establish relations was recently mentioned in a book, The Unsung Heroes of the Portuguese News Agency, which was published in Portugal in 2018.

In 1999, the Macao government asked Lusa to set up the press room for hundreds of journalists who would cover the handover ceremony on 19 December. The president of Lusa’s executive board recommended César de Sá for the job, commending his excellent work over the years. He took charge of the pressroom operations, working with dozens of journalists from the company to launch a special news and information service in Portuguese, English and Chinese.

After the handover of administration from Portugal to China in 1999, César de Sá returned to Lisbon in 2000 to work as an adviser for the news director of Lusa. But almost as soon as he unpacked his bags, they said: “Why don’t you go to Brazil? We have an office there that we need to deal with,” he recalls.

And in 2001, César de Sá set off first to Brasilia followed by São Paulo, where he worked as the regional director of Lusa for the next few years. “I travelled all over South America. And [my team of reporters] covered stories that nobody covered at that time – it was a great experience.”

As he neared the end of his tenure in Brazil, Macao government officials asked if he wanted to return to the city to set up an economic news agency that dealt with relations between China and the Portuguese-speaking countries. He didn’t hesitate.

“It seemed like a great opportunity. So I moved back in 2005 and together with Lusa we started a service agreement for the Macauhub News Agency in partnership with Macao Government Information Bureau for four years, after which I took private under my own venture for another 11 years.”