Amid the 16th-century Age of Discovery, the most important commodity was not one consumed or traded, but rather something intangible: knowledge. It was an invaluable asset, guarded by a select few where sharing fragments could be punished by death. Underscoring the clandestine nature of information, maps were often exaggerated and deliberately misleading – just in case they fell into the hands of a rival. Some propagated ideas that were entirely inaccurate, such as the early belief that the Indian Ocean was, in fact, an enclosed lake.

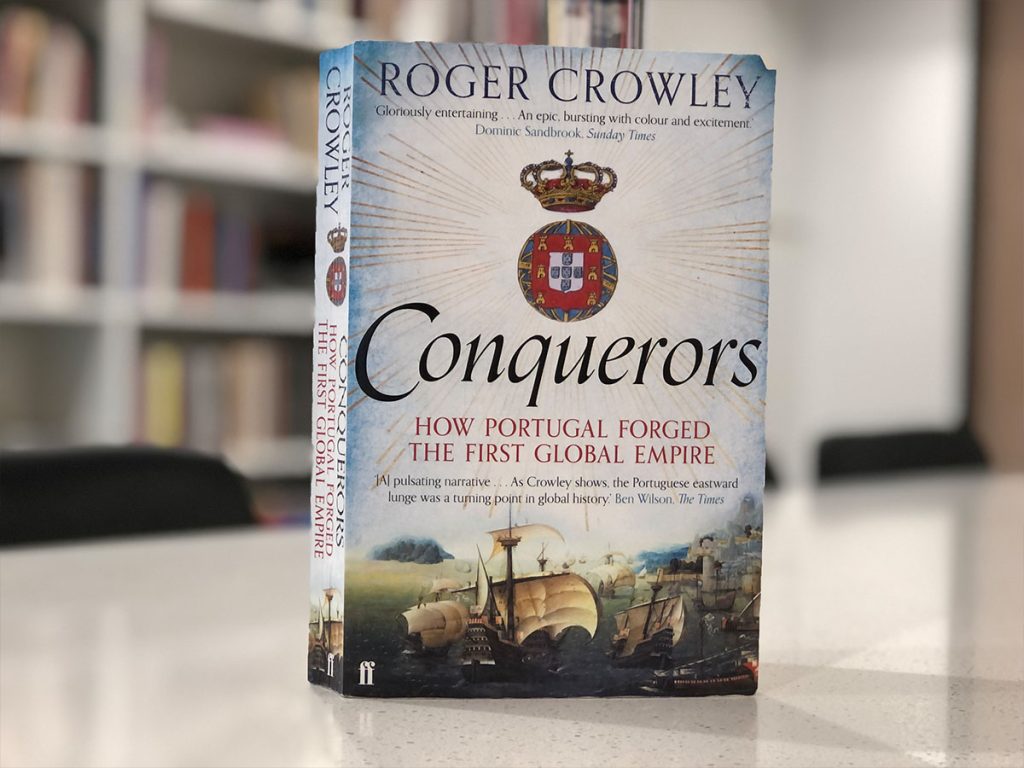

For the Portuguese explorers who sailed past the Belem Tower in Lisbon, each journey beyond the known boundaries of the time expanded the country’s intellectual capital and helped decipher fact from fantasy. Roger Crowley’s Conquerors: How Portugal Forged the First Global Empire narrates the tiny nation’s relentless ambitions, factoring “both the benign and malign” events during their global interactions with outside cultures.

[See more: Roger Crowley’s Spice is a must read for lovers of Macao history]

Tenacious endeavors are depicted, including the 80 frustrating years it would take the Portuguese to sail around the African continent, a landmass fifty times the size of the Iberian Peninsula. For nearly a century, each captain before Bartolomeu Dias would claim that the coast would turn east upon the next sea voyage, only to return to Lisbon with incremental information that would redraw world maps.

Gruesome encounters are also documented, including Vasco da Gama’s assault on the Miri, a pilgrimage boat that was later justified as retribution for an attack on Portuguese sailors just two years earlier. “We live in an age where it is impossible to avoid re-evaluating the deeds of those who came before us,” the Cambridge historian shares with Macao News, adding “I think every nation that has created an overseas empire needs to look at its past.”

Lisbon’s emergence

The maritime expertise and overseas knowledge brought back to Lisbon transformed the coastal city, enriching a local economy that had previously produced relatively little. Yet, despite those riches, crew aboard the nation’s departing fleets were often apprehensive. The oceans were unforgiving, and not every ship made the journey home. To fill the carracks, prisoners were incentivised with promises of freedom to join naval expeditions. Others were simply forced onboard.

The ocean crossings were both mentally and physically exhausting. Mutinies were fairly common. Those involved in unsuccessful uprisings were marooned on deserted islands, left with only a bottle of wine and a loaded pistol. Food was rationed (and often rotten), while vinegar was added to putrid water, consumed while pinching one’s nose. “Three drops of blood for a drop of water,” Crowley writes of those journeys.

As they traveled, the Portuguese carried cloth, mirrors, and brass bells, items that found little demand in countries that produced valuable spices and were accustomed to trading for gold. Instead, gunboat diplomacy proved more effective. They allied with rival tribes, fostering loyalties that lasted as long as they were convenient. Such tensions also existed between the viceroys. Francisco de Almeida arrested his successor, Afonso de Albuquerque, reflecting the power struggle among the Iberian captains the further away they were from the Patria.

Names inside the book may sound familiar to readers in Macao. A bust of Vasco Da Gama is erected just outside Tap Seac Multisport Pavilion near the Hotel Royal, while the nearby Rua de Afonso de Albuquerque runs up behind St. Michael’s Chapel and Cemetery. Students from Escola Portuguesa de Macau walk alongside a road named after Prince Henry the Navigator while visitors might walk a bit further south to reach the entrance of the Grand Lisboa.

[See more: Is Hong Kong more European than Macao? Writer Mark O’Neill thinks so]

For Crowley, those relics reflect both the diaspora’s uniqueness and genius. “Where the British empire lowered its flags and its people went home, the Portuguese embedded themselves around the world, detached from the mother country and in the process creating creole societies,” he comments.

When asked how he anticipates Portuguese readers, or readers of Portuguese heritage, will respond to a book written by someone who is not Portuguese, the author hopes that they will acknowledge the ruthlessness of their ancestors but also celebrate the ingenuity, curiosity, and uniqueness embodied in Portugal’s spirit and its pursuit of great adventure.

“I think it may be interesting for the Portuguese people beyond Portugal to read Conquerors to get an outsider’s view which may differ from that which they see from the inside,” he says.