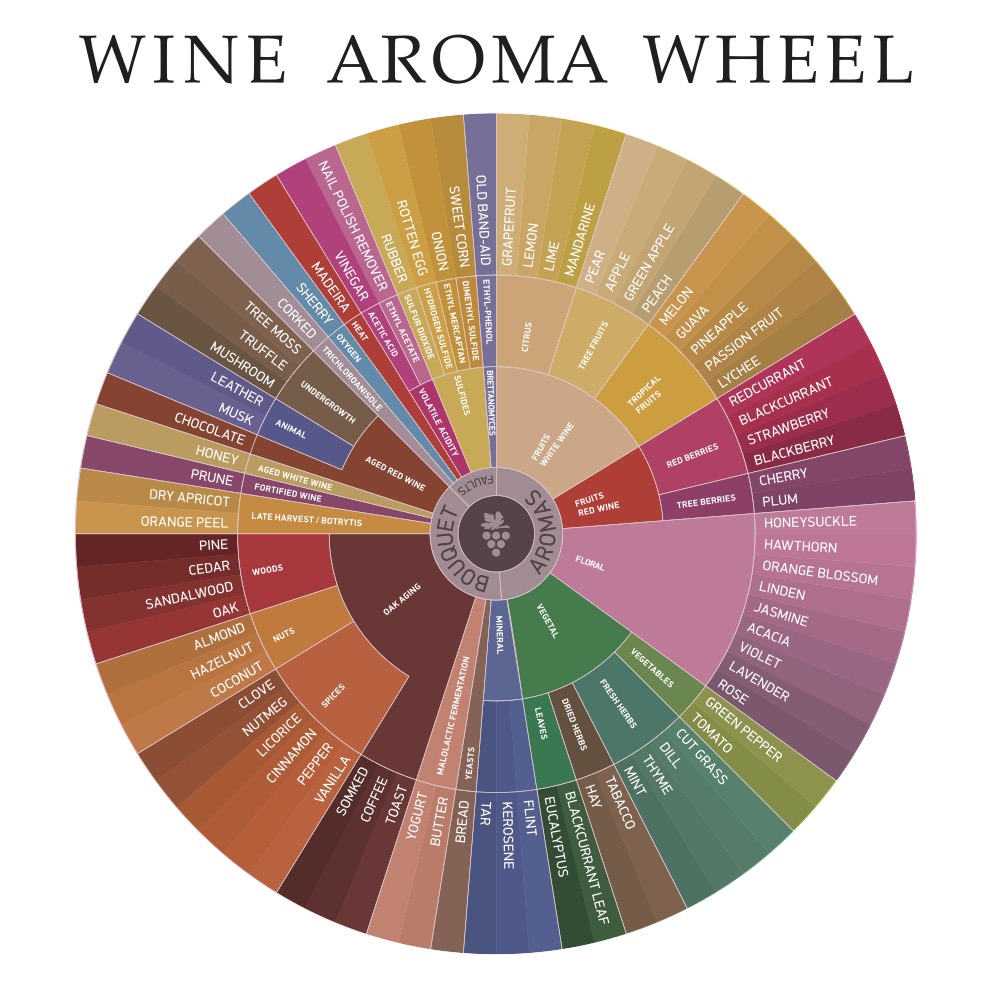

Part of the ritual of wine tasting is watching the sommelier swirling the wine glass gently, inhaling its aroma, and venturing some olfactory descriptions. While a layperson might only be able to distinguish between the smell of a red and a white, a connoisseur will have an infinitely wider vocabulary at their disposal. The wine’s aroma, a sommelier might say, can be compared to passion fruit, guava, cassis, prune, honey, violet, mint, and so on.

Wine is made from grapes, yet its bouquet – as the collection of scents is called – can tell a far richer story. I am sometimes asked if the wine contains additives to create this complexity. The answer is no.

The bouquet is a natural part of the fermentation and ageing processes, when different aroma compounds are produced along with alcohol and carbon dioxide. The better the wine quality, the more layered the bouquet. When a professional describes a vintage’s aroma as “ very complex”, it’s intended as a compliment.

Next time a bottle is opened, follow these steps to maximise your enjoyment. If you’re trying more than one wine, it’s a good idea to “reset” your nose between vintages. Professionals often do this by sniffing coffee beans. Assuming you’re not wearing any scented products, like a lotion, you can also sniff your arm.

Step 1: How to take in the bouquet of a wine

Swirl the wine and lower your nose into the glass. Don’t swirl excessively – once or twice is enough –and don’t swirl too hard. If you aerate the wine too much, the aromas will be harder to detect.

If you’re assailed by an unpleasant odour – wet newspaper and mouldy cardboard, for example, or rotten egg, burnt rubber, cooked garlic or even pungent farmyard notes – then the wine has been spoiled. Luckily, improvements in bottling technology mean that the chance of this happening is low.

Step 2: Distinguishing a wine’s primary aroma

Assuming there is no spoilage, the first thing to establish is a wine’s primary aroma, which comprises the fruity and floral notes of the grapes from which it was made. Each variety has its own olfactory profile.

Riesling, for example, gives off scents that can be compared to lemon zest, white flowers, peach, honey and even petroleum. Sauvignon blanc gives off fragrances of green apple, guava and sometimes green bell pepper.

Pinot noir has notable hints of strawberry, raspberry and other red fruits, while shiraz is distinguished by dark stone fruits, like plum and prune, with peppery and spicy accents.

It may seem like a lot to take in at first, but you’ll be surprised at how quickly you’ll be able to master such profiles. Science has shown that of all the senses, smell has the strongest connection to memory. Start with your favourite wines and branch out from there.

Step 3: Understanding the secondary aroma of a wine

This aroma is made up of the notes that are created during winemaking processes, such as oak fermentation and ageing and malolactic fermentation.

When wine is fermented or aged in oak barrels, it takes on additional complexity, depending on the type of oak used. The two main kinds are French oak and American oak.

French oak imparts notes like smoke and cloves. Classically, the heavier red wines are aged this way – Bordeaux, for example, or cabernet sauvignon. However, some whites benefit from oak ageing. Think of chardonnay or certain pinot blancs.

American oak lends a certain sweetness with vanilla, coconut and coffee notes. Many US. and Chilean wines are made with this kind of oak, which suits flavourful grapes like zinfandel and grenache.

Malolactic fermentation, meanwhile, is the process by which the sharp malic acid in wine is converted into smoother lactic acid, leading to a rounder mouthfeel. White wines that undergo this process, such as chardonnay and sauvignon blanc, often have a distinctive buttery quality with occasional hints of yoghurt.

Step 4: In older wines, look for a tertiary aroma

Wine must be aged for a least six years, and possibly eight, before it starts to develop tertiary aromas. These can be very distinctive.

Older white wines, for instance, take on a honey-like scent. Older reds can get earthy or hint at mushroom, leather and even truffle.

The older the wine, the more prominent these aromas are. It’s what sommeliers mean when they refer to a wine as “showing maturity” or “mature”. Such wines can be an acquired taste, but when you’re ready to go beyond the fruit-forward younger wines that new drinkers gravitate toward, there is a whole world of oenophilic richness to explore.

Want to know more? Check out the earlier instalment in Maggie Kim’s series, Wine-tasting essentials part 1: How to inspect a wine by sight.