Many people turn to music to get through sad, challenging times or celebrate momentous occasions. Melodies have the power to bring us together, lift our spirits, calm our nerves and soothe our wounds. It has also been an important tool in clinical therapeutic settings since 1789, when music therapy emerged in the US.

According to the American Music Therapy Association, the practice harnesses music-based treatments to help people with everything from developmental issues to depression, insomnia, substance abuse, rehabilitation and mood disorders. It is particularly helpful for patients with dementia or Parkinson’s disease, as well as children with learning disabilities or behavioural concerns.

In Macao, local practitioner 37-year-old Christal Chiang is one of just two music therapists in the city, compared to the neighbouring SAR, where the Hong Kong Music Therapy Association has been established since 1995 with 60 registered members. She provides therapy sessions for those in need, especially children and older adults.

Chiang, who has worked in the field for 13 years, first encountered this style of therapy in 2003 at Michigan State University in the US. Having played piano as a child, Chiang understood the power of music and knew it could help people — “I found more connections between music and life – with the rhythm, melody, harmony, everything” — so she decided to study music therapy and psychology. She graduated with a double degree in both subjects in 2008, then became a board-certified music therapist and brought her expertise back to Macao.

Striking a chord in Macao

Chiang returned home in 2008 and convinced administrators at Concordia School for Special Education, a few blocks away from the Macao Cultural Centre, that music therapy could help students. The school created a role for Chiang, who soon began therapy sessions with children who had autism and ADHD.

While she holds a US certification that is recognised by many other countries (like Hong Kong, Japan and Singapore), Chiang is unable to provide clinical services in Macao, because the city does not yet recognise music therapy as a qualified medical profession. However, she is able to conduct short-term, group therapy projects.

At Concordia, she helped her students improve their attention spans and cognitive abilities through songs and instruments. For example, Chiang altered the lyrics to the popular children’s song “The Muffin Man” to encourage children to choose coloured bells. This interactive exercise not only helped the children expand their vocabulary, but also improved engagement and focus.

Chiang took a break to work with neurological patients as a full-time music therapist at Singapore General Hospital for three years, then rejoined the school in 2014. Soon after, she began teaching music education students at the Macao Polytechnic Institute about special music education and music therapy.

She also shares music therapy with local associations and NGOs, such as the General Union of Neighbourhood Associations of Macao. At this day centre, where older residents can connect and find support, she helps those with Parkinson’s disease and dementia via group sessions.

She also helps patients recovering from strokes by organising choir groups at the day centre. Strokes can weaken the muscles around the vocal cords and affect coordination and communication, rendering speech slow and laborious but singing can help with this.

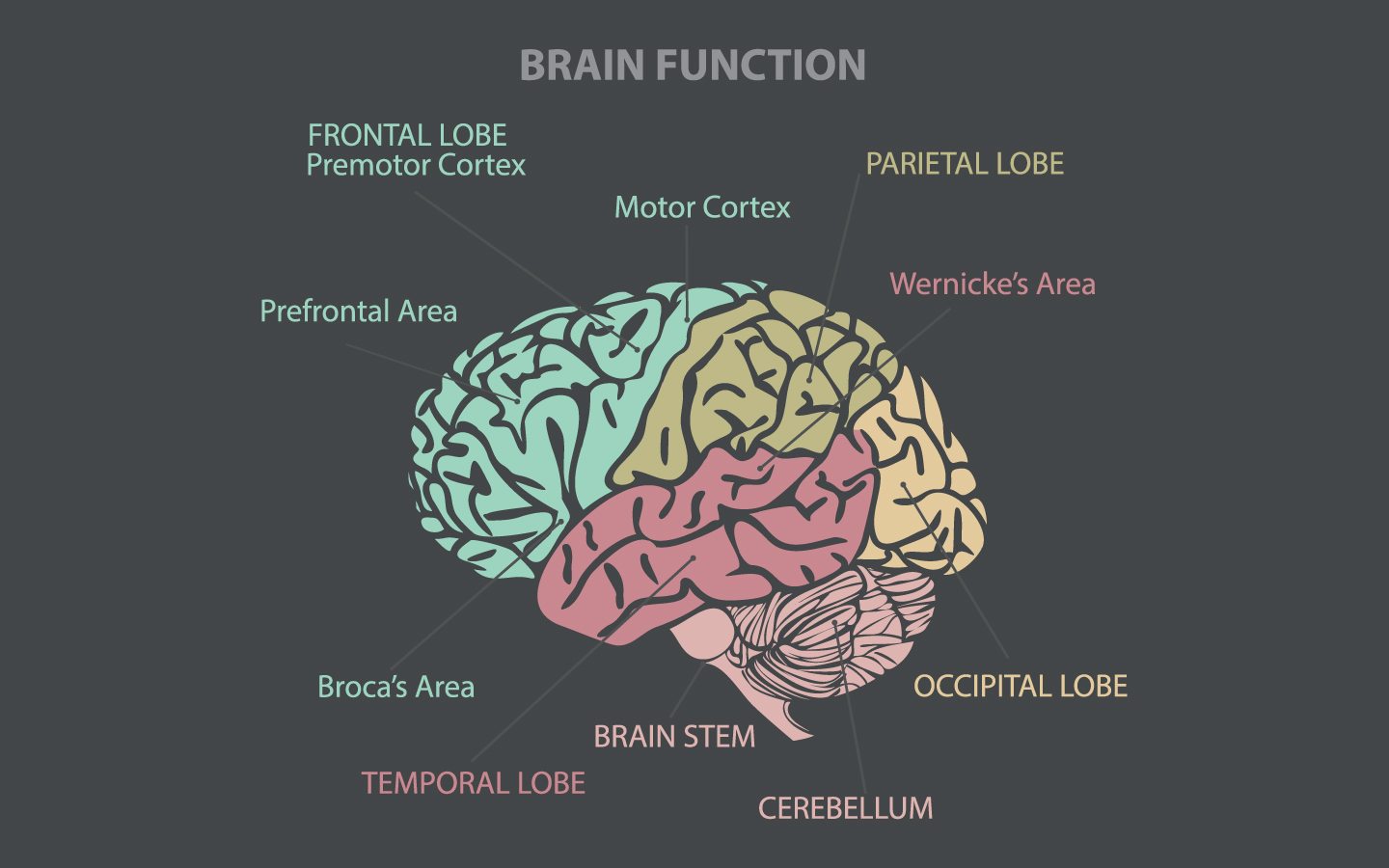

“If they have Broca’s aphasia [damage to the areas of the brain responsible for speech and motor movements] specifically, a very typical characteristic of this group is losing fluid speech but retaining the ability to sing, which all comes down to the neurologic system of the brain,” Chiang explains.

When used in tandem with speech and language therapy, singing can help individuals speed up physical recovery, reduce stress, improve mental agility and rebuild self-esteem. Before the pandemic, the group performed popular oldies from their youth at least twice a year for family and friends. Not only did the choir group offer participants a sense of accomplishment, but Chiang says it also provided a social network full of support.

The key to special education

Music therapy can be highly beneficial for youth, too. Music activates the brain’s temporal and prefrontal cortices, which are responsible for encoding memory and guiding complex behaviours, respectively.

When we learn song lyrics — even simple ones — it activates the brain’s cognitive function, while learning to play instruments improves coordination, strength, patience, communication and mood.

Chiang primarily helps children with special needs and developmental delays at inclusive education programmes and nonprofit organisations, including Fuhong Society of Macau, a local NGO supporting individuals with mental health conditions.

At Fuhong Society’s centre near Nam Van Lake, where Chiang provides group sessions for children under six, she incorporates a mix of instruments, singing and movements. “Some [children with special needs] have difficulties sitting down and focusing for long periods of time,” she says. “But in music groups, they can participate better because they tend to find it more fun.”

Musical activities with colours, numbers, steps and lyrics keep children engaged, while the act of singing and learning lyrics also support speech development, says Chiang. For some children, it can be hard to process everyday language because adults talk quickly. But when listening to lyrics, they have more time to process and understand each sentence.

Music therapy groups also provide a safe, positive space for children to work on social skills and collaboration, learn patience and work in teams. “Music can’t be done alone,” says Chiang. “When we play music together as a group, we have to wait for each other so we can make nice music.”

While it might sound like the children are simply taking a music class, it’s not that simple. Conventional music is about quality and performance skills; music therapy is about implementing developmental goals and evaluating progress, says Chiang.

Sometimes the goal will be to improve a child’s social skills like focus, eye contact, teamwork and confidence. Other times, Chiang aims to enhance speech and cognitive skills – such as learning the ABCs, colours or numbers – or physical skills, like coordination and strength.

Hoping to add to the growing body of research on the subject, Chiang is collecting data at Escola de Santa Madalena, where she provides music therapy, to document the benefits of music groups in Macao classrooms. “In these few months, we’ve seen some improvements among students in the schools’ music therapy session group,” she says, adding that results should be published this spring.

“Music is non-threatening, non-pharmaceutical and non-invasive,” says Chiang, who hopes to share the versatile practice with more people. “This makes it safe to apply in medical settings, rehabilitation centres, schools, nursing homes, as well as in psychiatric settings.”

And since so many people love music, patients often find it to be a social, pleasant way to heal and learn. “Music therapy is not Panadol,” adds Chiang. “It’s a holistic approach.”