Over the past few years, an increasing number of people in Hong Kong and mainland China have come to realise that gender is not a black-and-white matter. While the majority of people still identify as either male or female, not everyone fits into those two categories. Non-binary individuals may have a gender that blends male and female or experience a gender that changes over time; others may not identify with any gender.

As our understanding of gender evolves, so does the language we use to describe it. In English, some non-binary people use pronouns such as ‘they/them’ or ‘zim/zir’ to refer to themselves. In 2019, Merriam-Webster named ‘they’ the Word of the Year in 2019, while the Oxford English Dictionary added ‘Hir’ and ‘Zir’ to its lexicon, reflecting the widespread usage of gender-neutral, third-person pronouns.

Meanwhile, in Hong Kong and mainland China, the Chinese-speaking transgender community has been experimenting with the introduction of non-binary pronouns as an alternative to gender-specific pronouns, such as 他 (he) and 她 (she). To learn more about this linguistic evolution, we invite advocates in Hong Kong to walk us through the latest developments.

A brief history of China’s gendered pronouns

In contemporary Chinese, the character 他 (pronounced as tā) is specifically associated with men, however, that is a relatively modern construct. For much of Chinese history, the word served as a gender-neutral pronoun, covering feminine, masculine, and neutral pronouns – the equivalent of ‘he’, ‘she’ and ‘it’ in English. In many works of Chinese classic literature, such as 18th-century Dream of the Red Chamber, authors used 他 to describe male and female characters.

Due to increasing linguistic and cultural interactions with the West, a shift took place at the turn of the 20th century. Gradually, Chinese speakers started using 他 to refer only to men, since the character contains the radical 人 (meaning ‘human’ or ‘man’). In Chinese, a radical is a basic graphical component of a Chinese character that imparts linguistic meaning – not unlike a category or classification in English.

The usage of 她 as a female pronoun did not become prevalent until the 1920s, when the women’s movement in China shed light on women’s independence and individuality.

Renowned female writers, such as Bing Xin and Lu Yin, started using 她 in their writing, which was published in the fiction journal Fiction Monthly in 1921.

The introduction of the female 她 met controversy, though, because some women felt that it equated women with animals. For instance, women’s publication Women’s Resonance Monthly, released a notice in 1934, which stated: “Using a 人(human) radical [in 他] to represent men, a 女(woman) radical [in 她] to represent women, and a 牛(cow) radical [in 牠] to represent animals is an insult to women because it implies they are not human… we refuse to use the term 她.”

Despite the criticism, 她 eventually gained popularity as a female-specific pronoun and is still widely used today.

Introducing the non-binary ‘X也’

According to Kaspar Wan, founder of grassroots transgender information and support charity Gender Empowerment in Hong Kong, transgender individuals still debate whether it is necessary to create a pronoun for non-binary people who do not identify as 他 (he) or 她 (she).

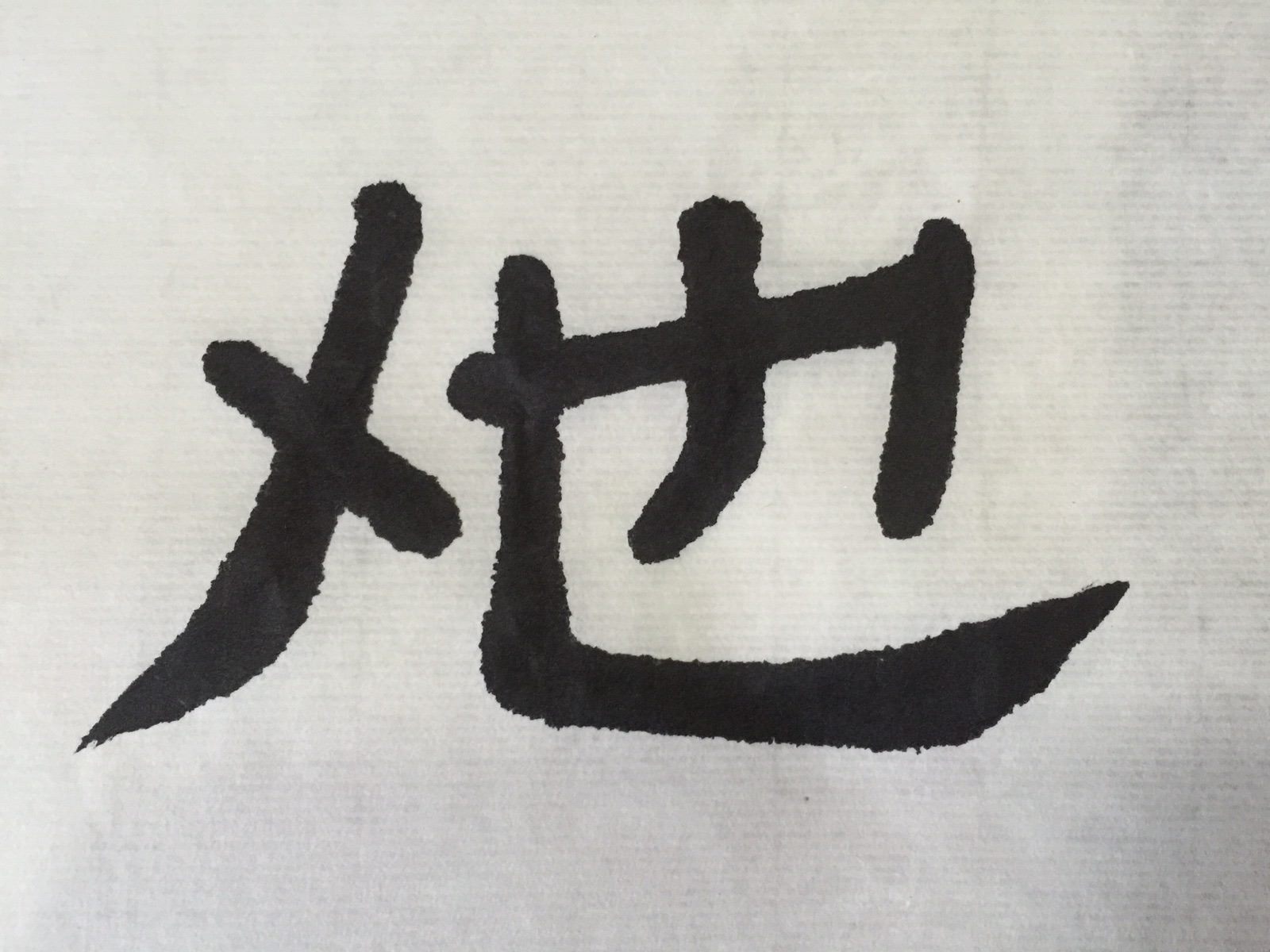

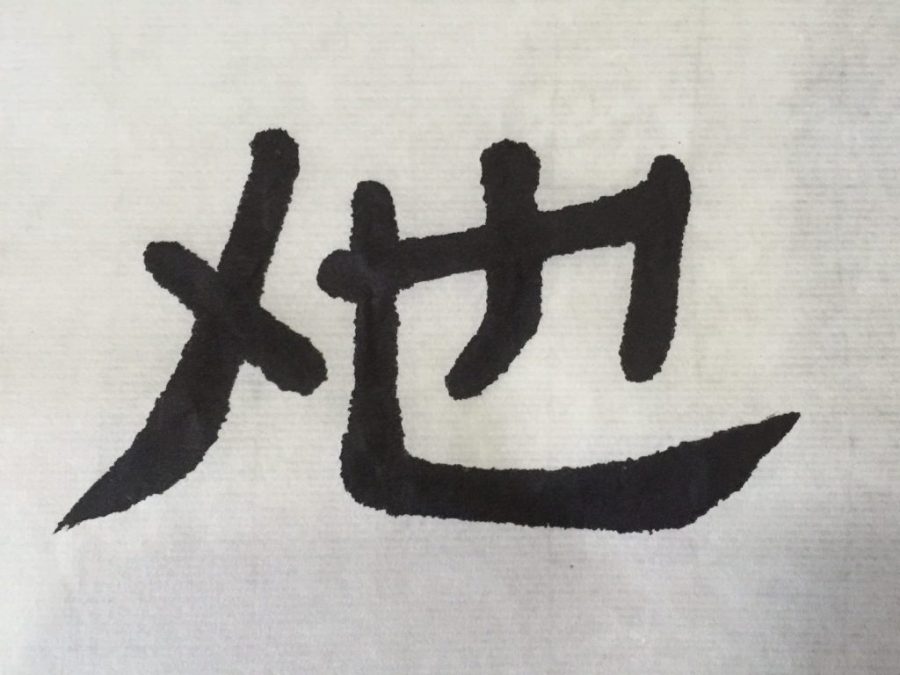

One example is ‘X也,’ which is a gender-neutral alternative to 他 and 她. Invented in 2015 by an intersex information platform called The Missing Gender 0.972, the word uses the English letter X to represent the non-binary community.

“I found it quite inspiring as it resembles Chinese words,” says Wan, who identifies as a transgender man. He later obtained permission from the platform to create stickers featuring this invented character, which he used to raise awareness about gender issues during a 2017 activism event in Hong Kong.

Though they improve inclusivity, invented characters like X也 pose linguistic and practical challenges. “For instance, how do you type X也 [on a phone or keyboard]? If you cannot type it, then circulation [and adoption] will be limited,” says Joanne Leung, a transgender activist in Hong Kong who identifies as non-binary. “Besides, there are situations where the writers won’t have room to explain to readers how and why an invented pronoun is used.”

As another option, Wan says that some non-binary Hongkongers also welcome the third-person, gender-neutral pronoun, 佢 (pronounced as qú), which is used in spoken form and in informal contexts, such as in tabloids, instant messages or social media.

Re-embracing ‘ta’

Meanwhile, in mainland China, many people are using the pinyin, ta in situations where a person’s gender remains unknown or irrelevant.

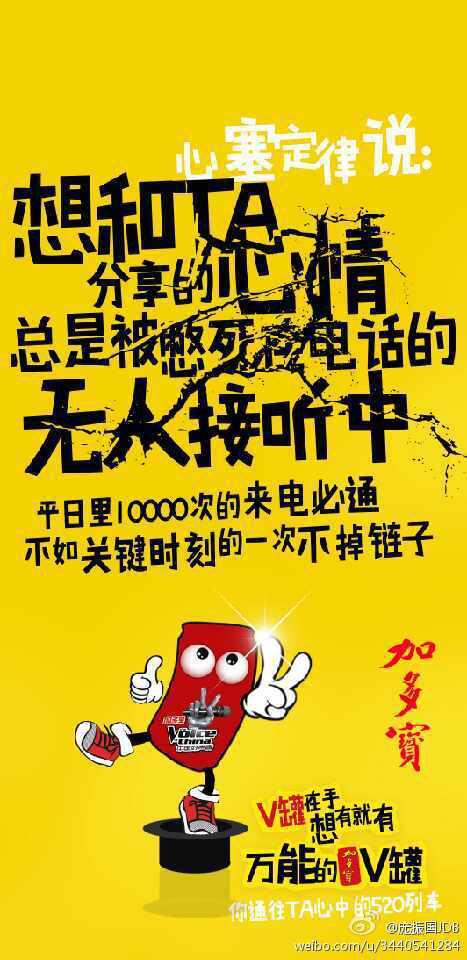

“Nobody knows when it started but, at one point, some people in mainland China came to realise that 他 and 她 represent male and female characters, so they started to use ta in Chinese sentences to be more inclusive,” explains Leung. “Some mainstream companies including China Central Television and JDB Group [a beverage manufacturer] are also using ta in their advertisements or Weibo posts when gender is irrelevant,” says Leung.

Although this phrase is less common in Hong Kong, Leung chooses to use ta because it is a more inclusive option. For instance, the activist used this gender-neutral pronoun when writing The Book of Transgender in Hong Kong: Gossip Boys & Girls, a guidebook for transgender people which Leung published in 2012. “[We] hope to remind everyone that respect for people’s gender expression and identity can be demonstrated through the language that we use,” Leung wrote in the footnote of the book.

When writing articles or op-eds for media publications tailored for the general public, Leung often uses 他 along with a brief explanation that this pronoun does not indicate a specific gender. “Why can’t we make people understand that 他 was originally a gender-neutral pronoun? If we keep arguing about the binary 他 and 她, we are actually falling back into the ideology of patriarchy.”

Wan adds that many of his non-binary friends feel comfortable being referred to as 他 in Chinese, especially those who were assigned female at birth.

“They understand that 他 was originally gender-neutral,” he explains. “Also, for transgender Hongkongers, the most important thing is to acknowledge that their gender identity is different from their assigned sex. If we don’t impose a 她 (she) on them, that is already a recognition of their gender identity.”