A professor at a local university by day and an artist by night, Hugo Teixeira was born in Portugal, raised in the United States, and now lives in Macao. The 41-year-old merges photography with sculpture and collage to create often large-scale installations that have been exhibited on three continents.

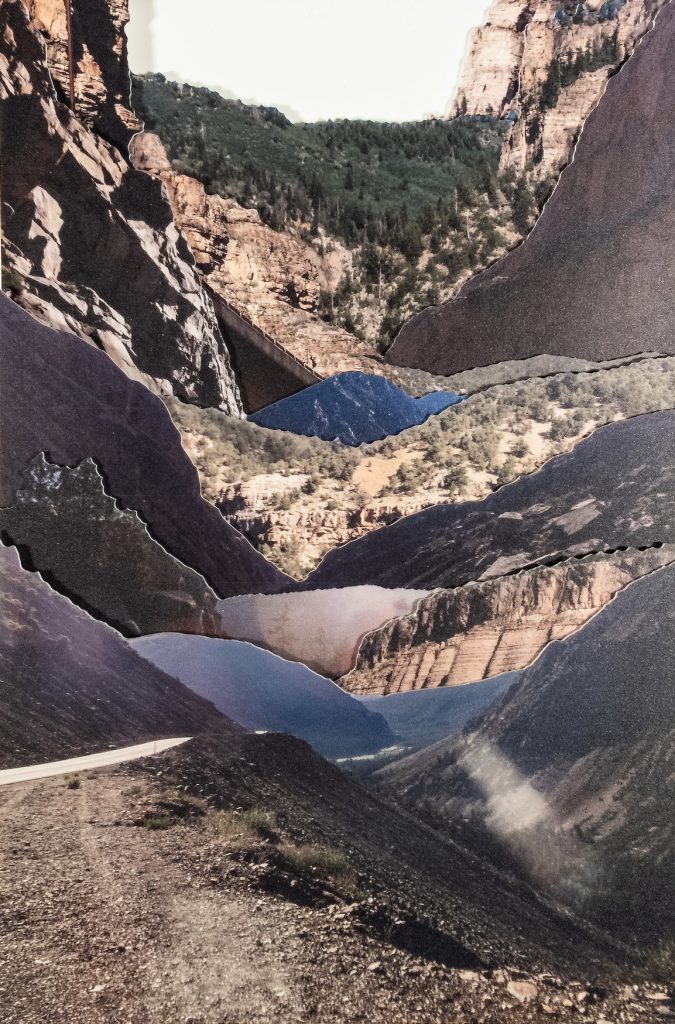

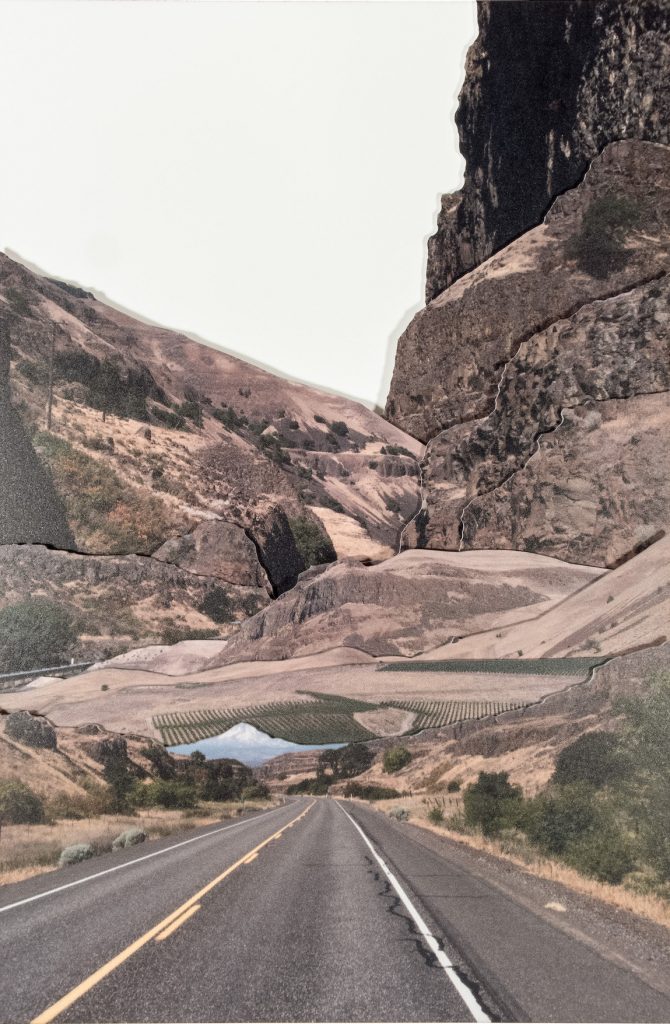

Examples of Teixeira’s work include Impenetrable labyrinths – a subtly three-dimensional (3D) collage of photographs featuring American canyons, hills and gorges – and ‘Dog Days on the Chaparral’ which was a layered installation of rugged scenes from southern Portugal.

Teixeira was part of the inaugural Silver List in 2021, alongside 46 other contemporary photographers selected by nonprofit photography curators, scholars, publishers, and critics. The Silver List showcases early-career photographers whose work is deemed important yet overlooked.

Teixeira graduated from San Jose State University in 2006 with a bachelor’s degree in linguistics. A diploma in documentary photography from Escola Técnica de Imagem e Comunicação in Lisbon quickly followed. In 2010, Teixeira was lured to Macao to teach English as a second language at various institutions in the city. After eight years here, he returned to the US to earn his master’s degree in Fine Arts, Photography and Related Media. This academic year, he’s back in Macao and working as an English professor.

Macao News sat down with Teixeira to find out about how he went from shooting 2D images to creating spectacular works of art in 3D.

Macao News: Photography was your first artistic medium. How did that start?

Hugo Teixeira: Growing up, I was always stealing my parents’ camera and they’d scold me because the film was so expensive. But it was something that interested me. I didn’t get my first camera till I was 18. I had several friends who were also into the hobby, and we encouraged each other. But even a little before that, at 16, I started travelling by myself and using photography to capture landscapes, people and history. The work I do now builds on that. Most of my recent work has to do with road trips and exploration. But not just travelling to a place; travelling through ideas and time, and sort of discovering myself in a more broad sense.

MN: What was your first camera, and what do you use now?

HT: The first camera I bought for myself was a Minolta Maxxum. The pictures I took were a little bit of everything: friends, university, and of my family. I was interested in its technology. It was the first camera I’d known to have manual controls, a manual focus, and nicer lenses. It was just interesting to see the world through a different, more mechanical eye. By 2001, I had my Rolleiflex, a medium-format camera. That’s the camera that forced me to sort of slow down and think more carefully about what I was taking pictures of.

Today, I use all kinds of cameras. Like different tools, each one has different functions that suit the needs of different projects.

MN: When did you get serious about photography?

HT: I was in a photography program at San Jose State [University] but couldn’t imagine myself as a professional photographer. I am from a working-class family and remember telling my mother that I chose a photography major. Her response was, ‘what do we tell the family?’

That also coincided with one of my first solo trips to Portugal, in 2002. I would take the camera out for eight hours a day and just take pictures around Lisbon, learning about the place. It was a very familiar place because my family was there – but at the same time, I’d never really explored it. So, the camera was sort of the excuse to go look more carefully.

MN: How did you transition into 3D art, and what do you call your finished works?

HT: I don’t know if there’s a word for them. Not that I’ve ever discovered. They’re almost too big to be mixed media. They’re sculptural, but also photographic.

The shift from 2D to 3D happened in graduate school, in 2019, when I was experimenting with collage. I started to appreciate how the light cast shadows on unfinished collage images – which led to experiments in making collages that weren’t flat.

But if you go further back, as early as 2010, I was working with old photographic processes on glass and metal. In these processes, the material becomes almost as important as the image. It’s only natural that the work then evolved into 3D forms that feature material and fabrication more prominently.

It also goes back to my upbringing, as I have an uncle with a machine shop [also known as an engineering shop, a place with heavy tools for drilling, sawing, thread-cutting, and the like] in the States. He’d work with metals and plastics to make parts and mechanisms for different industries. I worked with him growing up and learned a lot about tools and fabrications. And my dad was an amateur woodworker at home. So, I just naturally enjoy doing that kind of thing. I don’t like sitting at the computer and looking at the thousands of pictures taken that day. I get a feeling of accomplishment from physically building things.

MN: Tell us about some of your pieces. Do you have a favourite?

HT: The biggest one is about 2.4 metres tall. The challenge there is it’s impossible to transport, so I’ve only exhibited that in Rochester [US]. After that, I made a couple of smaller series. One was of Involuntary Landscapes, combining landscape photography and vintage photographs, and I put those together specifically for an exhibition in Macao in 2020.

My favourite is probably the largest piece from ‘Dog Days on the Chaparral’. It’s the one I worked on the longest, and the one that came out the way I imagined it. That was intended to be exhibited in my thesis exhibition. But because of the pandemic, it was all shut down. So, it was displayed at the Rochester Institute of Technology in 2020 instead.

Eventually, I had to destroy it. Because I moved to California, and it was just too big to transport. So I sold the wood to a guy who wanted to buy some wood.

I’ve exhibited photographs of it in New York City, though. I’ve also written about the piece in Houston Center for Photography. It is going to be recreated soon, at about the same size, for a photography festival in Bratislava. They contacted me a few months ago and said they’d like to recreate ‘Dog Days on the Chaparral’ after seeing it on my website.

MN: Could you explain how you make your 3D artwork?

HT: It starts with the photographs. I find [geographic] places which give me the forms I need and connect them. There’s a little bit of pre-visualisation, and I have a whole system for categorising the shapes of mountains.

The method then depends on the project’s size and material. But the basic process is looking at small images, matching them together, and then making bigger versions in the assembly.

From a quick one-hour photoshoot of a place, I’ll print hundreds of small pictures using four-by-six-inch glossy paper, the cheapest prints I can find. Then I’ll cut out contours and lay them out on a table, to see how the shapes work together. From about 50 possibilities, I’ll narrow it down to 10 to 12 images. After confirming the final images, only then do I print them large.

Those larger pieces assembled with wood are meant to look like the framing of a house in the US. And because they are so large, I use a heavy method of wooden joinery.

It takes months. It’s not hard or complicated, it just takes time. ‘Impenetrable Labyrinths’, from photographing to exhibiting, took about a year. I was working a full-time and part-time job as well, so this was just in my spare time. I guess part of it is just me; it takes me time. I don’t like to look at the images right away. I like to have that distance. If you have that distance of a few months, you see them more objectively. You’re not seeing, “Oh, remember this day, it was a great day.” You see, “This shape is useless,” and throw it away. You need to have that cold distance because that’s how people will see your work. They don’t have that emotional connection.

MN: What’s been your most memorable photography experience?

HT: My mother always told the story of when she was seven years old and living in 1957 rural Portugal. People were quite poor at the time and didn’t have many resources. One day she was walking to school, crossing a small river, and she got swept away and almost died. It’s the sort of story you hear when older people in the family get together and say, ‘I remember that time.’ Those can become part of you as well.

Anyway, I had to find that place. I remember hounding my mother saying, ‘you have to remember what it looked like or what was nearby. Was there a house? Were there trees?’ She kept saying, ‘I don’t remember.’ So, with very few hints, I went looking and think I found the place, though I can never know for sure. But emotionally and intuitively, it felt like that place. And that place is included in one of my artworks. It’s kind of an Easter egg hunt.

MN: What are your favourite places to photograph, both outside and inside Macao?

HT: My two favourite places outside Macao are Alentejo, in southern Portugal, near where my mother is from, and the California Chaparral, which looks the same. Both are Chaparral regions, with similar climates, plants and animals.

In Macao… anywhere. But I would say the densest areas. Between 2015 and 2017, I did a lot of architectural photography. Something I’ve just realised recently, coming back to Macao, is the connections between huge, tall buildings and mountains. Somehow they’re both mountainous and overwhelming. They inspire awe and rise from the horizon, sort of violating the sky.

During my first three years in Macao, I was living in Fai Chi Kei. It’s the most densely populated area, with some of the largest buildings. I remember living on the first floor and the building in front of me was 20 storeys high. I couldn’t see the sun. Even if I went to the balcony, I couldn’t see the sky.

MN: What are your plans for your art in the near future, and do you have any advice for aspiring photographers?

HT: My immediate goal is to set up a studio in Macao, so I can work a little more easily, have a few more exhibitions, and see where that goes. I do it really out of passion. Even if I can’t make a career out of it, I’ll keep doing it. It’s just that I need that creative outlet. So, it’s not like I have a specific goal for artwork in mind, except to make more.

To aspiring photographers, I say the same: make more work. Just photograph. Doesn’t matter if people see it, it doesn’t matter if people like it, you just have to do it. First, you have to be creating work that you like, and then people will also recognise that work. Work, work, work. That’s the main thing.