For nearly three decades, Dóci Papiaçám di Macau Drama Group has been keeping a tradition alive. Since 1993, this local theatre troupe has staged an annual production at the Macao Arts Festival. They perform entirely in the Portuguese-based creole language of Patuá – a mix of Cantonese, Malay and Sinhala language influences that is native to Macao. Today, the language – also known as Macanese patois – is spoken by only around 50 people, making it an endangered language, according to UNESCO.

Patuá theatre is a specific theatrical sub-genre that arose from this local creole, and comes from Portuguese Revista, characterised by its satirical comedic style which pokes fun at social issues and current affairs. For several decades, Patuá theatre was a favourite pastime for many Macanese and Macao Chinese. But as the language has waned, so has its theatre – until Dóci Papiaçám di Macau revived interest in it.

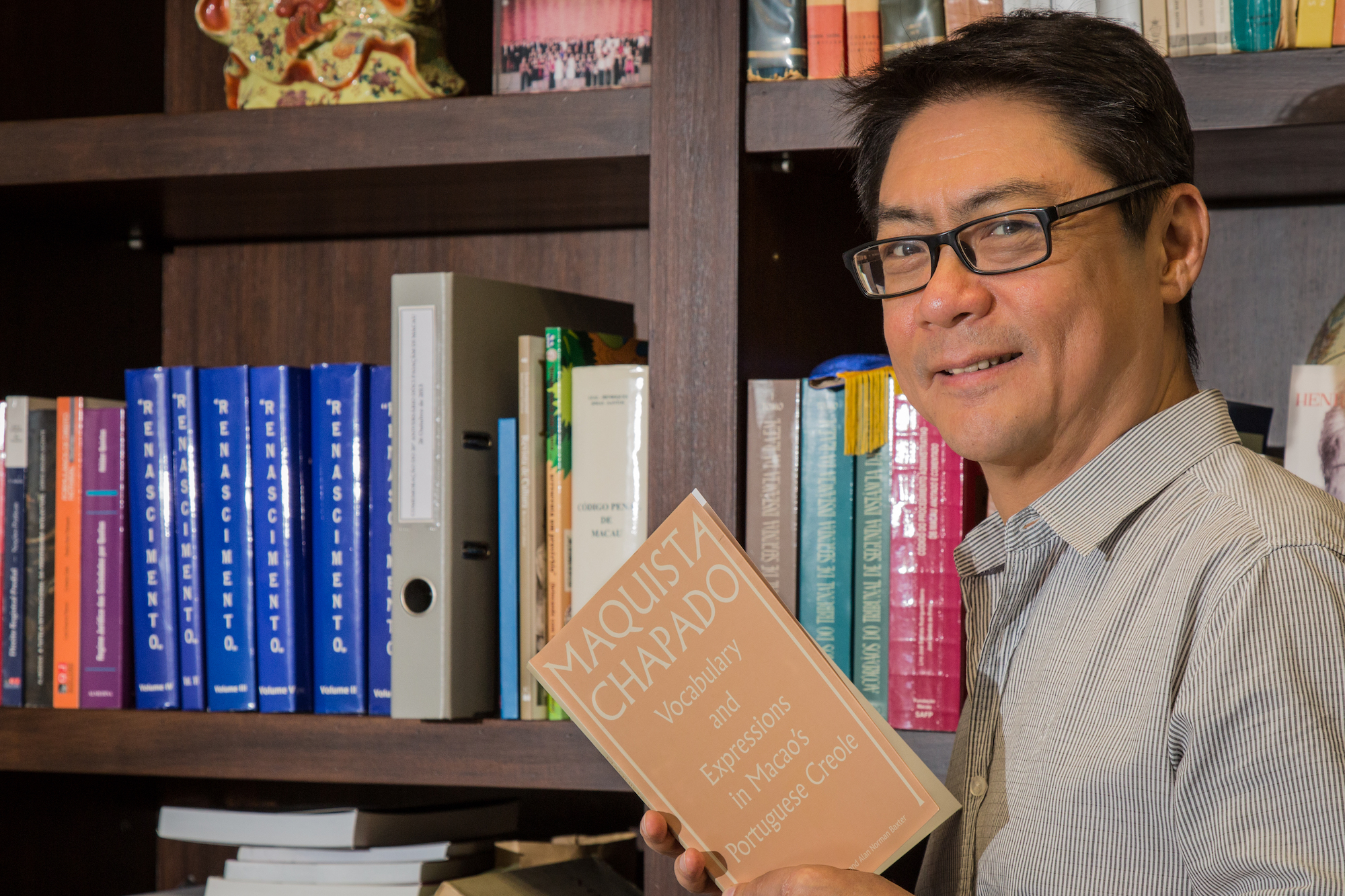

Miguel de Senna Fernandes is a lawyer by trade, but has also taken on a host of responsibilities within Dóci Papiaçám di Macau. He writes most of the group’s scripts in Patuá, directs them, and has plans to publish them in Portuguese, English and Chinese.

The group’s plays have been listed as part of Macao’s Intangible Cultural Heritage since 2012. Recently, however, they received national recognition, landing a spot on China’s fifth National List of Representative Items of Intangible Cultural Heritage. Senna Fernandes says it’s accolades like this that reflect a growing interest in Patuá.

“Every year, we are invited by the government to perform at the Macao Arts Festival,” says Senna Fernandes. “With the inclusion of Patuá theatre as an intangible cultural heritage, I think this shows a growing respect and recognition for the language.”

The group’s latest play, “Boss for a Day”, debuted at the Macao Cultural Centre from 15-16 May, and was performed in Patuá, with subtitles in Chinese, Portuguese and English.

To learn more about this rare local language, and Dóci Papiaçám di Macau’s attempts to preserve it through theatre, we spoke with Senna Fernandes.

Macao News: Firstly, can you explain what exactly is Patuá?

Miguel de Senna Fernandes (MSF): Patuá is a Portuguese-based language intermingled with many other old languages historically used in the South China Sea or Indochina regions. It was spoken by old Macanese families around the 18th and 19th century.

In those days, when visitors arrived in Macao, they would need to stay for many years, because of how time-consuming and costly it was to travel anywhere. This ensured more stability among the settler community, and gave rise to a new local culture, so it’s likely that this language has its origins in at least the late-18th century.

Back then, it was a despised language. It was believed that people should speak Portuguese well, and Patuá was seen as a very badly spoken form of Portuguese. Some of Patuá’s linguistic influences include Malay, Konkani (from India), Spanish, some English, and more recently Cantonese, which came about only during the early 20th century.

MN: Where did you learn Patuá?

MSF: I learned the language indirectly, by eavesdropping on my grandmother as she chit-chatted with her friends. When my father bought the first books of the late Adé dos Santos Ferreira [the famed Portuguese poet who wrote in Patuá], I devoured them.

When I finally got the chance to see my first Patuá play – also written by Adé – in 1977, I understood about 90 per cent of it. In 1993, when I wrote my first play for Dóci Papiaçám di Macau, I was still learning, but I had largely mastered the language.

MN: Tell us the story behind that first play! How did you get into Patuá theatre?

MSF: In honour of the re-opening of the Dom Pedro V Theatre, [one of the first Western-style theatres built in East Asia in 1860], a group of people from the Macanese community wanted to revive Patuá theatre.

My father [the late Macanese writer Henrique de Senna Fernandes] was asked to write a play for the occasion. He told me he was worried he wouldn’t be able to meet the public’s expectations – he could write prose but felt that a play required a different perspective than he could offer. I started making some suggestions, and eventually I wrote a short, 15-minute skit. After that, I kept writing plays in Patuá, and performing them in Macao.

At first, we would only perform locally. But in 1995, we flew to San Francisco and Sao Paulo in Brazil to perform. We’ve also performed in Porto and Lisbon. Since 2007, we’ve performed at the Grand Auditorium of the Macao Cultural Centre annually for the Macao Arts Festival.

MN: How would you describe your playwriting style? What themes do you normally tackle?

MSF: I would call it social satire. The plays I write are comedic, almost like a sitcom because you have very normal situations with ordinary people facing everyday problems that people can relate to. It’s not the characters themselves that are funny, but the situation they find themselves in.

MN: Can you talk about what the recognition as an intangible cultural heritage means to you?

MSF: Firstly, to clarify: it’s not the language itself that is recognised, but rather the Patuá theatre. However, the language plays a central role in the distinct identity of this type of theatre. So for me, recognising Patuá theatre represents recognition of a broader culture that is unique to Macao, no matter how few people still speak it.

MN: How do you think Patuá theatre reflects the unique character of the city?

MSF: Our stage is a cultural platform that represents all parts of Macao: we have Macanese, Portuguese and Chinese actors. Because this is a Patuá show, it is mostly performed in Patuá. But we also include Chinese actors who speak Cantonese, Portuguese actors who speak Portuguese, and some English, too. With so many different elements, this makes it a multicultural platform that reflects our audience.

MN: How long does it take to prepare for a performance and what are the most challenging aspects?

MSF: For our most recent play, we rehearsed for around two to three months, for three evenings a week. The whole process is challenging, but that’s the beauty of it. If I didn’t like rising to challenges, I wouldn’t have been able to create as much as I have.

Everyone in our theatre company are amateurs, with little to no experience on the stage. I don’t have time to teach them how to act or how to overcome stage fright, and that’s why group support is important. Some are more versatile than others and can pull off any kind of role. But some have limitations and that’s fine. I don’t demand more than what they can do. It’s a very endearing experience, and we depend on one another. This is what it means to be human.

MN: Is it challenging to find people who can perform in Patuá?

MSF: If we only chose actors who could speak Patuá, [our group] would have been dead in the water before the handover! Almost all of the actors had to learn from scratch. They learned to read, then their pronunciation would be corrected, and then their dialogue. After a month, they start to realise the meaning of what they’re reading. They’re not learning alone, but with their fellow castmates as they interact on stage. I think it’s the most simple and direct way of learning a new language.

We have never held an audition. I rely purely on my instinct. If I see a person with no stage experience, but speaks a bit of Portuguese and is willing to try, I try to find a role for them.

MN: What do you find the most rewarding?

MSF: I think for most of us, the best reward is the applause. During rehearsals, there can be so much frustration, with people working so hard. Then it’s the big night, and you hear the audience laughing and it’s so satisfying to have accomplished that together.

The enduring relationships we build between the cast are also rewarding. The show only takes place for two nights every year but those bonds last. In the end, we’re a big family.

MN: Do you think that these performances are helping to keep Patuá alive in Macao?

MSF: As a group, we are trying to preserve our collective memory through these annual performances. We want to raise awareness of the social and cultural aspects of the language. Nowadays, since we all use Cantonese, English or Portuguese, there’s not much space for Patuá. Younger people don’t know much about it. It only survives in the theatre.

YouTube playlist of past Dóci Papiaçám di Macau plays: