Macao Museum’s current exhibition, A Tale of Three Cities: Guangdong-Hong Kong-Macao Greater Bay Area and Export of Silk Products in the Ming and Qing Dynasties, distills an ocean of historical, economic and artistic information about the Greater Bay Area (GBA) into one drop.

Through the export of tea and cotton, porcelain and silk that rolled from the Middle Kingdom to the west, China became seen as a land that brimmed with dynamic colours and refined prints, where refined crafts and luxurious raw goods were replicated in alluring designs for decades after.

The extraordinary exhibition offers variety and breadth. It showcases items and exhibits that range from maps, paintings, hand-painted silk, tapestries, furniture, porcelain and historical documents.

A Tale of Three Cities opened at the Guangdong Museum in December 2020 and is touring the Macao Museum until 13 March 2022. The exhibition is expected to make its final stop at the Hong Kong Museum of Art in June 2023.

“We want to explore two fields – the flourishing economic exchange between the east and west, and the role that the GBA [Greater Bay Area] played in exporting silk to the west,” says Gabriel Chi Wai U, the Macao Museum’s exhibition curator.

Part of the collection cannot tour because of the delicate nature of some items, such as the embroidered tapestries, displayed for the first time. The Macao exhibit has welcomed almost 10,000 visitors.

The embroidered tapestries convey the influence of Guangdong embroidery in the region, and compliment the East-meets-West cultural exchange that happened in Macao.

The hand-embroidered tapestries were woven in Guangdong at the behest of several local Chinese merchants in the late 19th century and presented as gifts to the Macao governor Carlos Eugénio Correia da Silva and businessman Bernardino de Senna Fernandes. The former item is a thank-you to the Macao-Portuguese government for its contribution to the city, while the latter honours the businessman.

Both tapestries feature messages in the center, surrounded by Chinese motifs of flowers, birds and people including children, elderly people and noblemen. The palette, a characteristic of Guangdong embroidery, remains vibrant thanks to the high-quality thread count and dyeing, along with highly intricate embroidery skills.

Additional exhibits exclusive to the Macao tour is a complementary display of Chinese dresses and wedding gowns made in different Guangdong embroidery techniques – gold and bead embroidery.

A local resident ordered the two gowns be made by a tailor at Lyndhurst Terrace in Hong Kong. They feature the technique of Xiangyun Sha, the practice of soaking a silk fabric in juice made from yams native to Guangxi and Guangdong provinces.

Chinese industries in western eyes

The exhibition sheds light on the West’s curiosity of various Chinese industries, such as silk, tea and porcelain. China’s foreign trade began to rise in the Ming dynasty (1368-1644) and continued to flourish in the Qing era (1644-1911).

Foreign trade prospered because of its tribute system, the imperial China’s diplomatic network with other east Asian vassal countries which bestowed gifts on Chinese officials. In the 1400s, Ming Admiral Zheng carried silk, porcelain and textiles to the West.

The tribute system sustained trade and diplomatic relationships between China and other east Asian vassal countries, including Japan, Korea, Vietnam and Ryukyu, a kingdom within a chain of Japanese islands.

In 1684, Emperor Kangxi of the Qing Dynasty allowed foreigners to trade with China in four cities: Guangzhou, Xiamen, Songjiang and Ningpo. That same year in Guangzhou, the Thirteen Hongs (also known as the Thirteen Factories) were established along the Pearl River to produce items that were traded with western merchants from Holland, Britain, Sweden, the US, France, Spain and Denmark. In 1757, Emperor Qianlong closed all the ports, but Guangdong continued to play a major role in the country’s export trade.

The exhibit’s paintings depict the Thirteen Hongs through various decades. “You can see the evolution of the economy flourish and changes of the scenery in these paintings,” the curator notes.

In the early and mid-19th century, British painter George Chinnery depicted the life and landscape of the region through landscapes and the production processes. Their works were sold in the west. The technique used in the western paintings influenced Guangdong painters such as Tingqua and Lamqua, who also sold their work to western buyer.

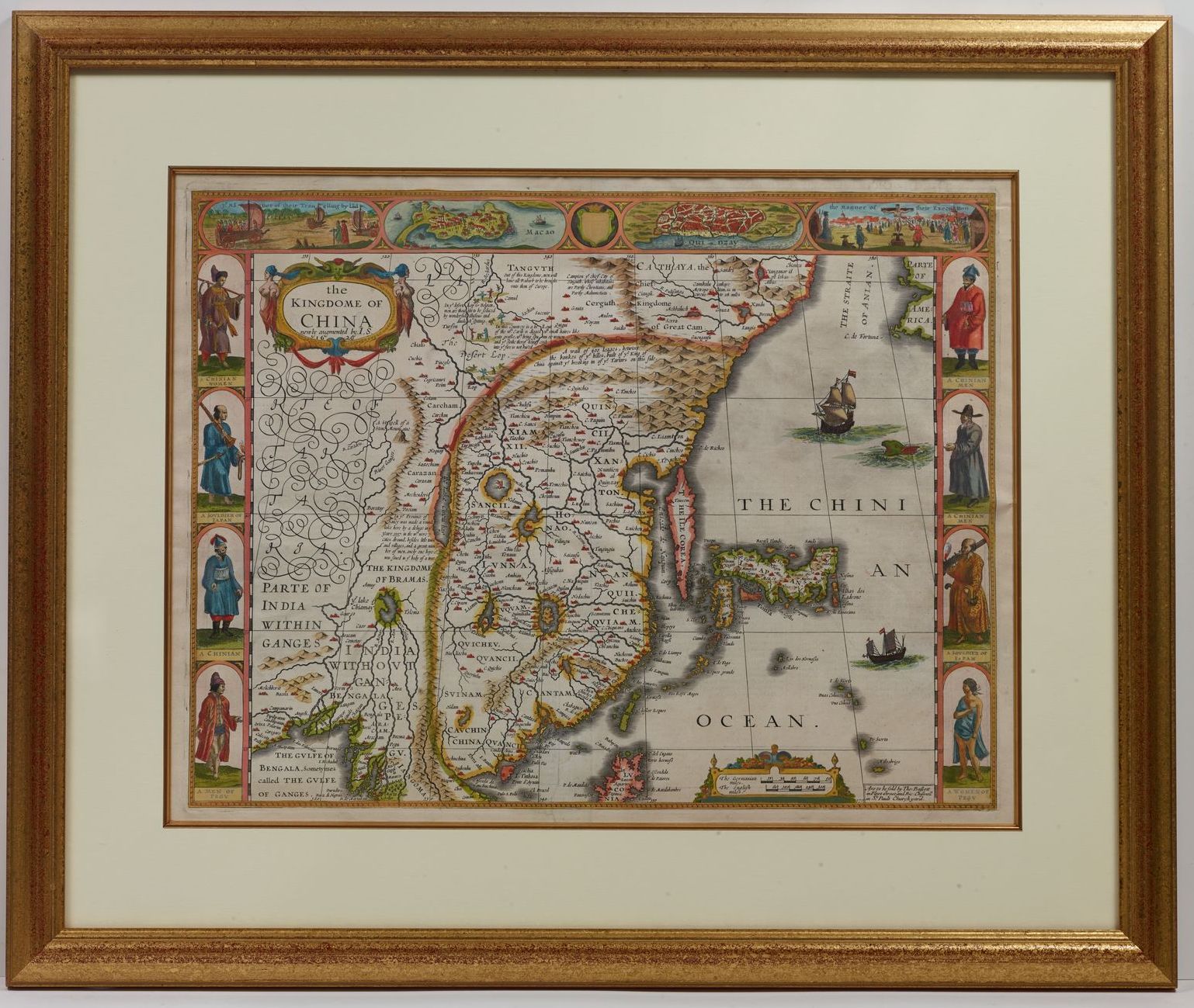

A map of the Chinese kingdom, painted by British cartographer John Speed in the 17th century, shows the painter’s unique perspective of China’s significance as he illustrated with foreigners dressed in silk.

Some paintings of The Thirteen Hongs, an important harbour along the Pearl River in Guangzhou, illustrate the economic flowering of East and West. Hong is a Cantonese term referring to a licensed business. Western ships unloaded and sold their goods to Chinese merchants, who sold them to locals.

One painting reveals a line of buildings carrying the flags of different Western countries, signaling where merchants from those places sold their goods.

A stitch of time

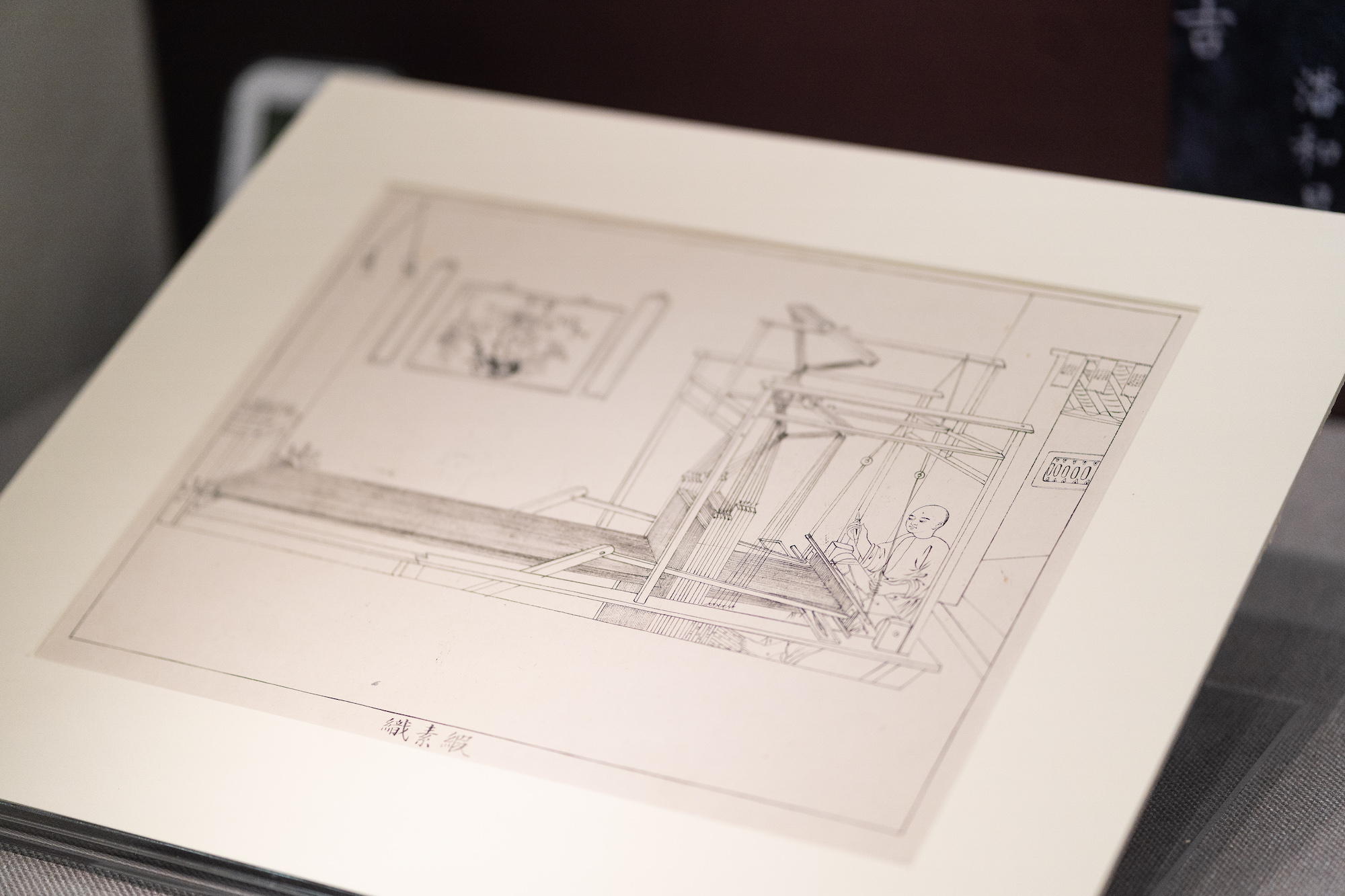

An 1844 sketch of a satin weaving by Guangdong painter Tingqua, once an assistant to British painter George Chinnery, shows the artist’s meticulous illustration of the production. The curator believes that after the First Opium War, some French merchants and envoys arrived to trade with the Qing dynasty. An envoy bought this painting from Tingqua’s workshop.

Chinese industries – tea, porcelain, silks and embroidery – fascinated the Western world and became the subject of paintings that attracted buyers.

A set of 12 paintings depicts the process of manufacturing silk fabric — from bathing silkworms, to spun cocoons, to weaving and dyeing fabrics to cutting cloth. Curator U says that he has seen paintings depicting tea and cotton production. Western buyers often bought such works as decorative art.

Chinoiserie on trend

Chinese aesthetics lured outsiders, with motifs of flowers, birds and mountains. They were painted on porcelain, paper and silk and first appeared in the 17th century. The European imitation of Chinese and east Asian styles strongly influenced the way Chinese industries manufactured their products. Chinoiserie was reflected in wallpaper, bedding, curtains and furniture.

In the exhibit, a depiction of a westerner’s room shows a tablecloth and bed linens made in beige satin embroidered in the Guangdong style. In the fabric, a lotus pond, lotus leaves, mandarin ducks, kingfishers and dragonflies are rendered in gentle greens, oranges, cherry reds and blues. Mandarin ducks, loyal to their partners, are a symbol of love.

A blue satin women’s robe is embroidered with flowers and birds. Such delicate clothing was popular in China’s foreign trade in the late 19th century. Their loose tailoring and exotic patterns gained popularity with Western women who wore them as morning gowns and night robes.

It was a style that remained popular and, like the other items, showed how traditional Chinese influences lingered in the western mind.