Raised by farmers in a humble home in Shunde, Guangdong province, Iao Tun Ieong learned diligence and persistence at a young age. As the eldest of four children, Iao was born in 1945, right around the Dragon Boat Festival (known as Duanwu Festival in Chinese) as his name states in Chinese.

Working on a farm, his parents could not afford much day to day, week to week. But they wanted more for their eldest son and worked tirelessly to give Iao the “best gift”, which was “to be sent to school,” he says.

At the age of 15, he began studying at Shunde No. 1 Middle School, a boarding school, where he displayed deep dedication to both his schoolwork and family.

“Every Saturday, I walked [17 kilometres] home from school, and it took me four hours,” recalls. “On Sundays, I walked the same distance back to school.”

He soaked up as much as he could, and his mathematics teacher, in particular, influenced him greatly. “I really admired my math teacher. I aspired to be as good at math as he was,” recalls Iao. “I worked on 10 extracurricular math questions after school every day.”

Iao was also passionate about science, which eventually led him to study biology at South China Agricultural University in Guangzhou from 1963 to 1967. In addition to an RMB 17.5 (MOP 23) per month grant awarded to Iao by the university, his younger brother, who had become a farmer, supported his studies. When Iao talks about his siblings, he radiates joy and gratitude. They have a tight bond and still visit each other often, he says.

Upon graduating in 1967, Iao worked countless odd jobs to make ends meet in Guangzhou, a relatively expensive city at the time. He recounts the five social classes back in the old days – workers, peasants, merchants, students, soldiers – and says, proudly, that he has done them all, including a two-year training in the People’s Liberation Army Garrison in the Doumen district of Zhuhai, Guangdong and in Hunan province.

Iao Tun Ieong started his first teaching job in 1970 as a math and biology teacher at Dongfeng Middle School in Zhongshan, Guangdong. He was 25 years old at the time, and his eldest student was 17. He recalls this period with satisfaction: “The income was low. I earned RMB 51.5 [MOP 64] a month. But I was close to my students – we played sports and hung around together after school. These were fond and happy memories.”

After five years at the school, he worked at a factory for the next five years. In 1983, he relocated to Macao with his wife – who was born in Macao – and his children to start a new chapter. But at first, Iao was focused on finding another job in education.

He initially worked as a secretary in a school, then eventually secured a job as a biology teacher at Hou Kong Middle School in 1988. And in 1992, he furthered his education studies with a remote programme administered by Shanghai Normal University for two years.

When Iao joined Hou Kong, the school saw more than 8,800 students, with roughly 65 in each classroom. “Our management team comprised one principal, three vice-principals, and some directors. It was difficult to manage such a large number of students in terms of their behaviour and learning. They smoked, fought and some had troubled backgrounds.”

Hou Kong is known as one of the more patriotic schools in Macao. The former principal, Du Nam, became known for raising the first five-starred red flag in Macao on 1 October 1949 – the founding day of the People’s Republic of China – with the teachers and students at the school in attendance.

She also carried out Mandarin teaching and flag-raising ceremonies on the school’s founding anniversaries and China’s National Day – even during the Portuguese administration of Macao.

“Principal Du has influenced the school and me a great deal. She demonstrated her patriotic spirit throughout her life,” recalls Iao. “The first word of our school motto is loyalty. She has taught us at Hou Kong to be loyal to our country and people.”

She also shared Confucianist philosophies that resonate deeply with Iao as an educator, such as: ‘Education without discrimination for all who are willing to learn.’ “This is important,” he says. “In her time, even kids with criminal pasts had the opportunity to study; she also said we could find hidden gems among our students.”

In 2000, Du stepped down, and Iao became the school’s principal while continuing to teach biology. The responsibility has been a significant motivator for the academic, who says it was challenging to follow Du’s footsteps.

“Principal Du is a world-renowned educator. The stress of taking over her extraordinary work was incredible. The only thing I could do is to try my best,” he recalls feeling during the transition. “Thankfully, I have had a great team to support me.”

Over the years, he has kept some of Du’s principles close to his heart; however, he also saw opportunities for change. “We firmly defend Principal Du’s belief here [at Hou Kong Middle School], but we apply an elite-training approach at [sister school] Hou Kong Premier School Affiliated to Hou Kong Middle School [HKP].”

Iao is also the principal of HKP, which was established in 2010. The school provides a rigorous, international education to intellectual students from kindergarten to secondary school. Classes cover everything from the sciences and humanities to arts, music, languages and social skills.

Citing a high bar for entrance exams, Iao says English language proficiency is one of the main focuses. As such, the school has hired many English-speaking teachers, including some from the US. The international atmosphere, he says, helps students develop a cosmopolitan perspective to better contribute to society and compete on the international stage.

“Always learn from the others,” says Iao, of his career motto. “We may not have the ability to learn everything from one person or place, but just a tiny bit is enough.”

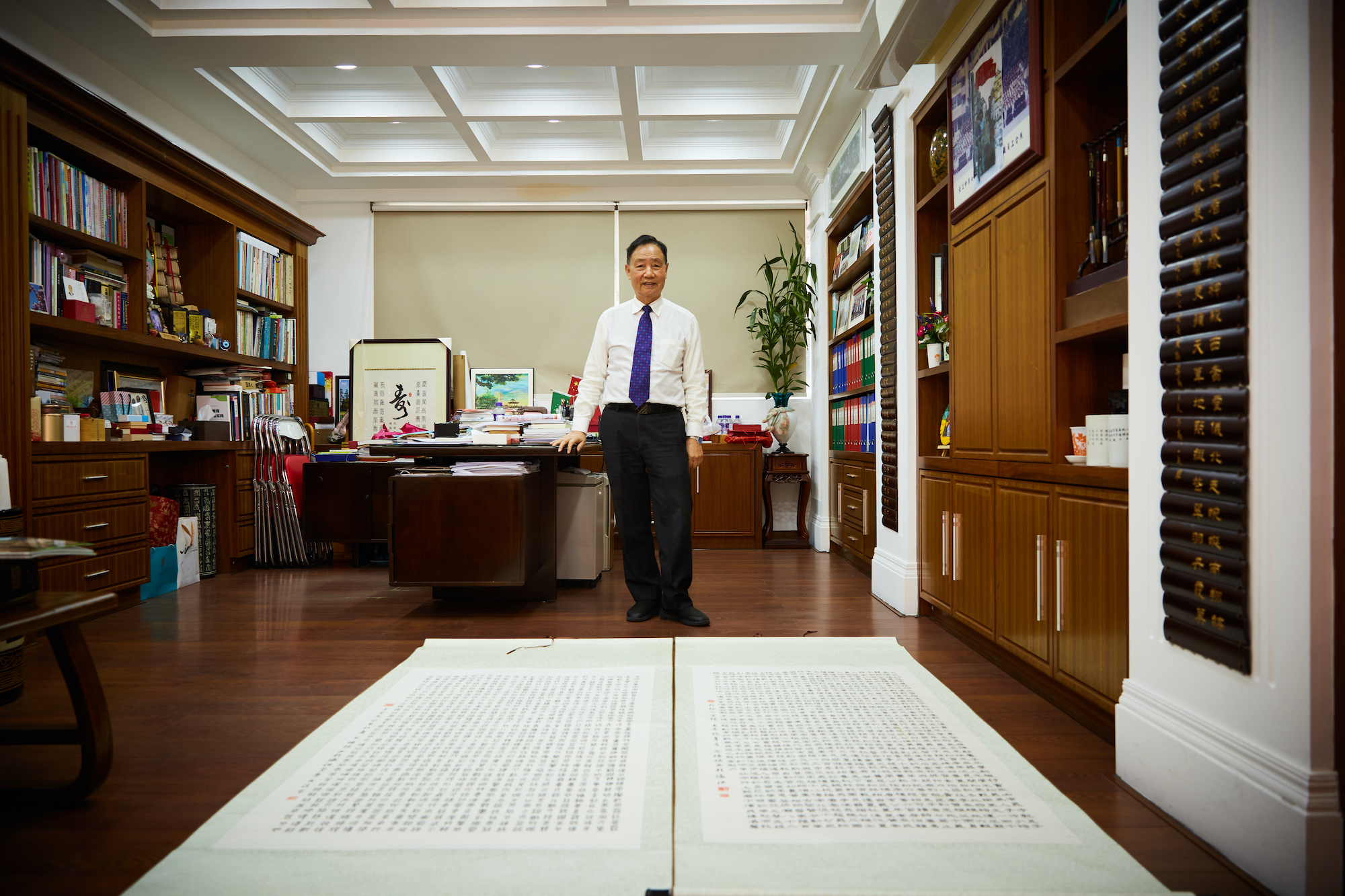

He applies this modest attitude to his work and Chinese calligraphy, an art form he started practising in 1996. That year, while serving as the vice principal of Hou Kong, Iao led over 30 Chinese teachers to participate in calligraphy workshops. Since then, the art form has developed into a lifelong passion.

For Iao, calligraphy nurtures one to be calm, persistent and attentive. It not only allows practitioners to gain a deeper understanding of Chinese culture but also enhances one’s cultural awareness and attention to detail.

Practising every Saturday and Sunday, Iao has exhibited his works alongside his peers in the past. He is also the vice president of the Macau Association of Chinese Calligraphy, where he studies many calligraphy styles. Of the many scripts he practices, his favourite is “clerical script”, which he values for its elegance, symmetry and order.

He also teaches calligraphy at Hou Kong school, in an effort to share his belief that writing “good calligraphy” is one way to be a “good Chinese” person. In the “cultural corridor” outside of Iao’s office, the teacher’s passions for education and calligraphy converge as he proudly exhibits students’ calligraphy artwork.

Over the past decade, Iao has embraced other unconventional teaching methods, too. For instance, he adopted an ‘independent learning method’, which he says was first introduced by Du Longkou Middle School in Shandong Province.

Under this style of instruction, students are encouraged to learn, explore and manage their work independently. They’re also expected to partake in discussions with teachers, practice public speaking, develop critical thinking skills and express themselves through writing.

“Many of our students are not confident enough to express themselves. We hope to encourage them to learn, think and debate independently,” says Iao, adding that the school often uses a traditional teaching tool, the chalkboard, to facilitate such exercises. “Teachers write questions on the chalkboards; students are encouraged to write down their answers, then other students debate and correct their peers. The chalkboard is a place where they can learn to express themselves proactively and independently.”

Iao also believes that a strong sense of community spirit is essential for youth development. In 2008, he began introducing a series of festivals – Sports, Reading, Gratitude and Technology – that occur every year at Hou Kong. “I once led our teachers to visit Shanghai QiBao High School, which arranges eight festivals a year,” he recalls. Inspired, he chose to introduce four festivals at his own school soon after.

As physical wellbeing, literacy and innovation are key components of his teaching philosophy, Iao felt this combination of festivals would make sense for Hou Kong. In addition, he hopes to instil an attitude of generosity in his students through the annual ‘Gratitude’ festival, where students usually arrange charity sales to support disaster relief efforts across the region.

Looking back on his career, which has spanned five decades so far, Iao has witnessed considerable improvements when it comes to access to quality education in Macao, especially after the establishment of the SAR in 1999. Free schooling and government support have ensured that children across all levels of society have an opportunity to learn, he says.

In the future, he hopes to see a greater emphasis on diverse perspectives, social skills and critical thinking. “Students can learn a lot by memorising things, but they lack social and practical opportunities. Hopefully, there will be more educational and social activities so that they can diversify their development and cultivate a cosmopolitan perspective,” he says.

“Mandarin and English proficiency are also important. Through language training, students will be able to better contribute to our country, Macao, and the world at large in the future.”