People love to talk about change in Macao. What is actually remarkable is how much things stay the same – at least when it comes to the territory’s historic architecture. If you want proof of the success of the city’s preservation efforts, you only have to compare the street scenes of today with the sketches of the artist most associated with Macao: George Chinnery.

Born in London in 1774, Chinnery has gone down in history as a rambunctious character. He was immortalised as Aristotle Quance in James Clavell’s novel Tai Pan, and again in Timothy Mo’s celebrated novel An Insular Possession, where Chinnery appears as the corpulent painter Augustine O’Rourke.

The truth, of course, is more nuanced. Patrick Conner, who wrote the first in-depth study of Chinnery’s life and work, called him “an international star, a really extraordinary artist” and praised him especially for his “incredibly fluent drawings of the China coast.”

Chinnery made most of those drawings in Macao, where he settled in 1825 and stayed until his passing in 1852. The works depict an enchanting city of Portuguese architecture, cobbled streets and Chinese temples – much of it still here. But don’t just take our word for it.

The compact dimensions of Macao’s Historic Centre mean that it is best explored on foot. The composite illustrations below are made by joining Chinnery’s 19th-century sketches with the present day scene. Take a look at them as you walk, and marvel at the ease with which you can follow in the great painter’s footsteps.

Ruins of St. Paul’s

Start at Macao’s most iconic structure. Chinnery made his sketch of the Church of Mater Dei before it was almost entirely destroyed by fire. Built by the Jesuit order in the early 17th century, it was one of the largest Catholic churches in Asia until it was razed in January 1835, leaving just its edifice behind.

The site is today referred to as the Ruins of St. Paul’s after the eponymous college that once stood next to the church and was regarded as the first Western-style university in East Asia. Together with the Mount Fortress, the area remains the symbolic heart of Macao.

Chinnery’s pen and ink drawing, The Church and Steps of St. Paul, was made just three months before the conflagration, but what is remarkable is how its most eye-catching elements – the steps and the church’s façade – are unchanged.

Holy House of Mercy

A six-minute walk south brings you to the Macao branch of this famous Portuguese charity. Established in Lisbon 1498, the Santa Casa da Misericórdia (Holy House of Mercy in English) is dedicated to the wellbeing of what it calls the “most unprotected” members of society, including the sick, the disabled and the very young.

The Macao branch was set up in 1569 in a neoclassical building built on the orders of then Bishop of Macau, Belchior Carneiro Leitão, and featured the city’s first clinic of Western medicine. By the time Chinnery came to sketch his Crowd outside the Casa da Misericordia and Leal Senado in 1840, the institution had been around for 271 years, offering health and other social welfare services.

The Holy House of Mercy is the white building in the middle of the photograph and the perspective chosen by Chinnery for his drawing – looking toward the Leal Senado (or the present-day Municipal Affairs Bureau building) – remains much the same today.

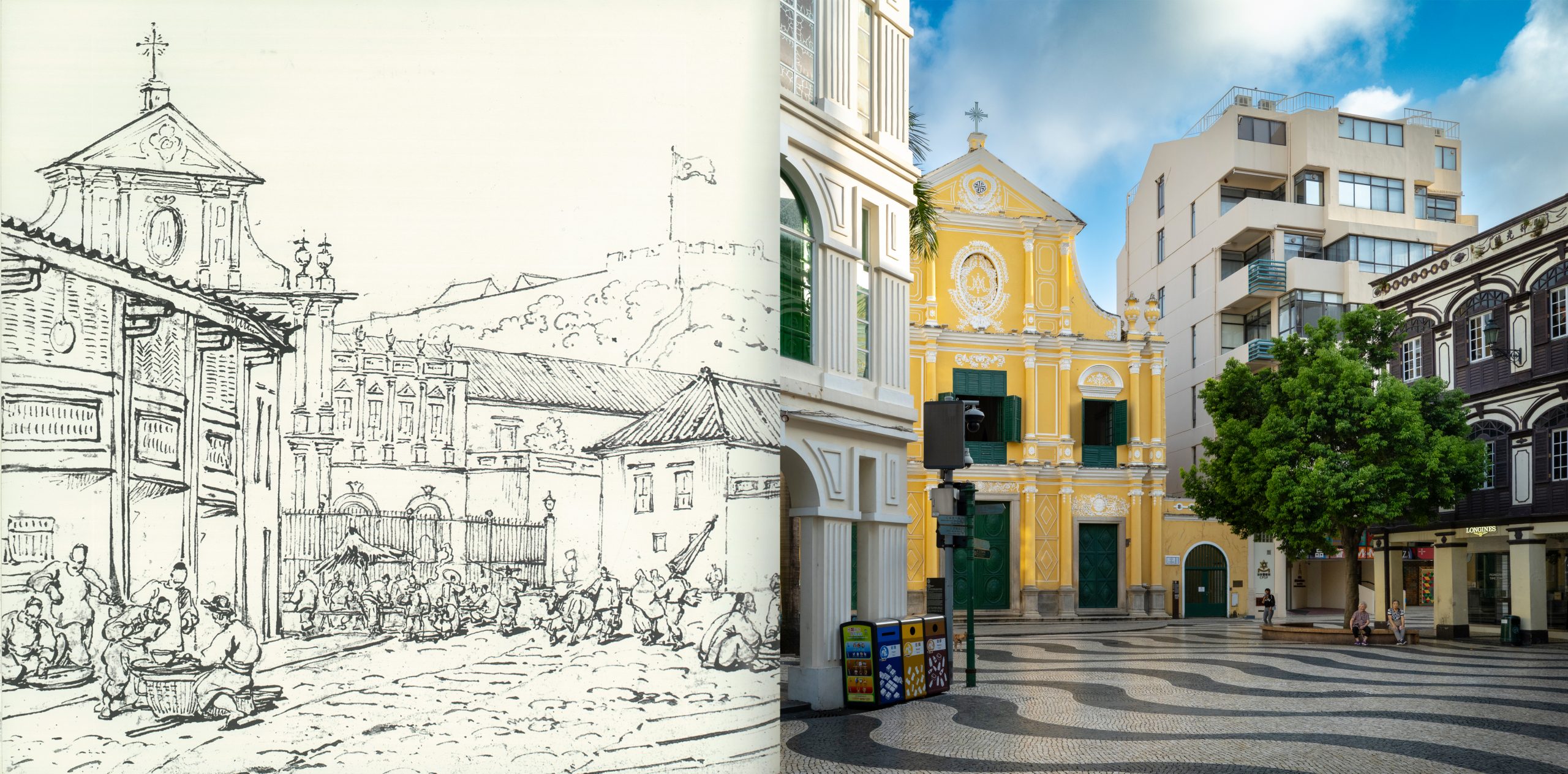

St. Dominic’s Church

Just a three-minute walk away across Senado Square is the baroque, lemon-yellow St. Dominic’s Church, one of the most charming buildings in Macao’s Historic Centre. Presumably, Chinnery thought so too when he came to make his sketch, which shows hawkers and market stalls outside the church railings. The traders appear in several drawings of the church made by Chinnery at different times, suggesting they were a regular fixture at this location.

By the time of Chinnery’s arrival in 1825, St. Dominic’s was a long-established place of worship. It had been built 238 years earlier, in 1587, not by Portuguese but by Spanish Dominican priests who came to Macao from Mexico.

In 1834, the monasteries of Portugal were dissolved at the orders of Prime Minister Joaquim António de Aguiar, and their assets were seized. For a time, St. Dominic’s became a barracks, a stable and an office, before it was later restored as a church.

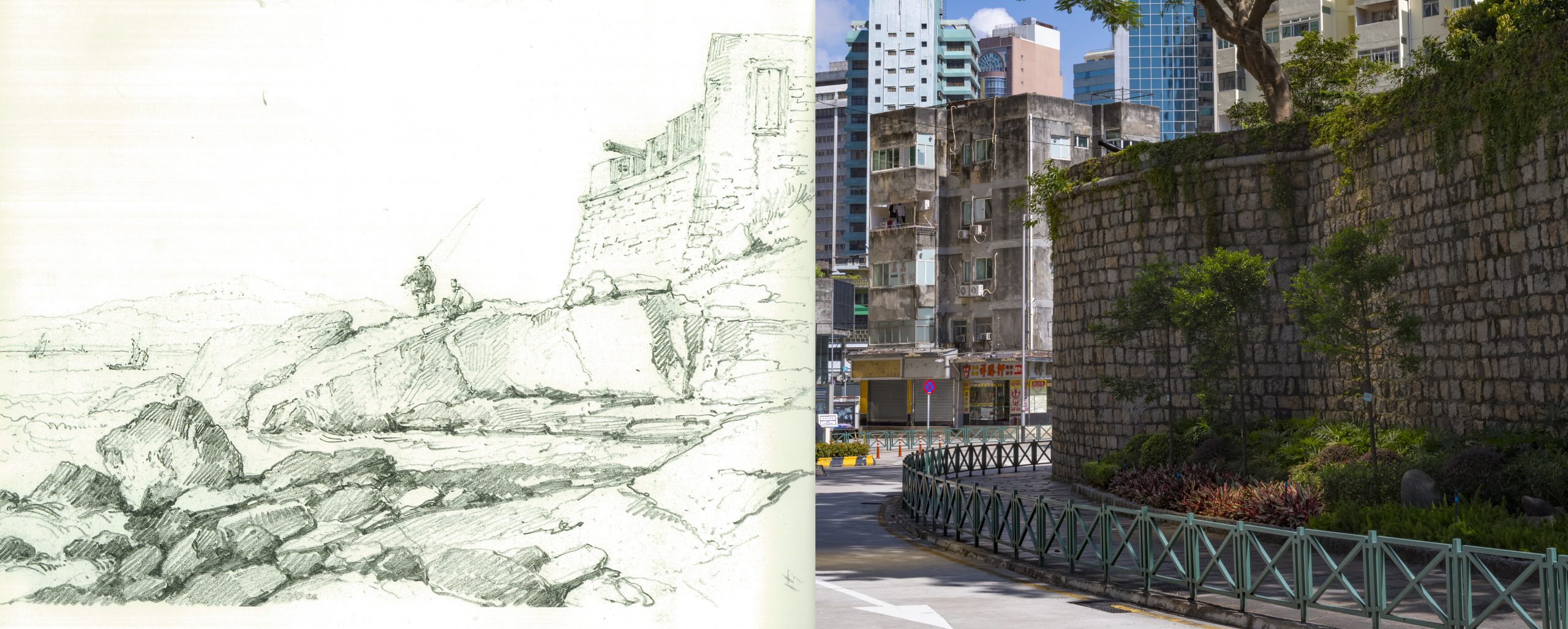

St. Francisco Barracks

A 10-minute walk in a southeasterly direction brings you to Macao’s military heartland. As Chinnery’s sketch attests, the present St. Francisco Barracks used to be right at the waterfront, at the very end of the old Praia Grande. Today the impressive walls are ringed by busy roads and lie in the looming shadow of the Grand Lisboa hotel, but through half-closed eyes, it isn’t too difficult to imagine waves lapping on the shore and fishermen perched on now vanished rocks, as Chinnery once saw them.

The site began life in the early 17th century as an artillery battery, with a long-barreled cannon that could fire a 16-kilogram ball a distance of almost 2.5 kilometres. The six-metre-high walls were not added until later. Barracks were built on the site in 1864 and survive today as the headquarters of Macao’s security forces and police.

A-Ma Temple

A 30-minute walk from the barracks takes you to one of the peninsula’s earliest structures.

Built in 1488, the A-Ma Temple predates the Portuguese administration of Macao and was already of great antiquity when Chinnery sketched it in 1833.

The temple is dedicated to the goddess Mazu (also known as Tin Hau or simply A-Ma, meaning mother) and Chinnery’s drawing, The A-Ma Temple with two sketches of a boatman at his oar, connects the Chinese sea goddess with the seafarers who were her principal devotees. Confucianism, Taoism, Buddhism and various folk beliefs are all represented in the temple complex, which consists of six different buildings.

Some believe that the temple gave the city its name, with Macao being a Portuguese rendering of the Cantonese A-Ma-Gau, or mother’s bay. Even today, the temple is instantly recognisable in the fast, flowing lines of Chinnery’s pen.