Mozambique inaugurated Daniel Chapo as its fifth president on Wednesday. He takes the top office amid heavily disputed election results and ongoing protests, reports the BBC.

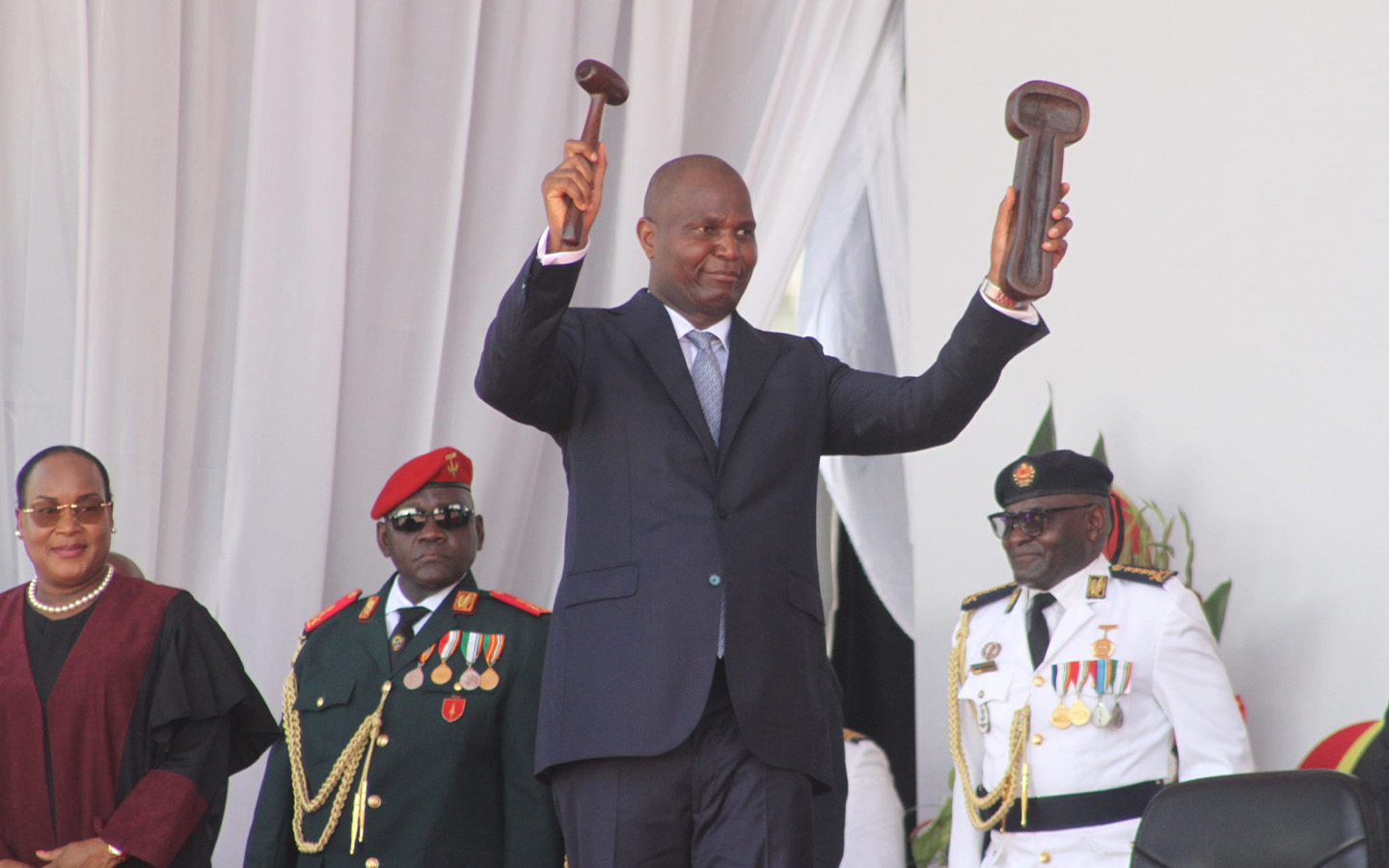

Chapo accepted the mantle of leadership in a subdued ceremony at Independence Square in central Maputo attended by over 2,000 guests, including the presidents of South Africa and Guinea-Bissau. Three of the five parliamentary parties – MDM, Renamo and Podemos – boycotted the ceremony and hundreds gathered outside to protest under the watchful eyes of heavily armed police.

Election observer group Plataforma Decide told the BBC that eight protesters were killed by police, most supporters of Chapo’s Podemos-backed opponent, Venâncio Mondlane, who had called for a three-day national strike coinciding with the swearing-in of parliament on Monday and the Wednesday presidential inauguration.

The Constitutional Council declared Chapo the election winner with just over 65 percent of the vote in late December, despite broad consensus among international observers and domestic organisations that the 9 October election was marred by voting irregularities and fraud. “Chapo is someone I admire greatly … however, he is assuming illegitimate power,” Mirna Chitsungo, a civil society activist, told the BBC. “He is taking power in a context where the people do not accept him.”

The 48-year-old leader is the first president of Mozambique to not fight in the country’s civil war. Both he and Mondlane, 50, were born as the war began, their childhoods shaped by a conflict that killed around a million Mozambicans between 1975 and 1992.

[See more: Mozambique braces for more protests ahead of a divisive presidential inauguration]

Chapo worked as a radio and TV host, a legal notary and university lecturer before getting into politics in 2009. As a member of Frelimo, the ruling party since Mozambique declared independence in 1975, he rose up the ranks to become the governor of Inhambane Province in 2016, where he served until declaring his presidential candidacy in May 2024.

Throughout the campaign, Chapo promised to turn around the economy, reduce bureaucracy and put a halt to corruption – promises that many young voters seemed to put little stock in given that his win continues nearly a half-century of one-party rule in the country.

However, supporters like Chitsungo believe that Chapo will be a departure from Nyusi’s “violent governance style” which led to more than 300 dying in the post-election protests. In spite of the way in which he came to power, “Chapo is a figure of dialogue and consensus,” Chitsungo explained to the BBC, saying she believes he could work with Mondlane to meet many of the demands motivating the latter’s supporters.

Addressing those demands and grievances, and sometimes breaking with his ruling Frelimo party, will be key to Chapo’s success, analysts told the BBC. They said a good first step would be sacking the country’s Police Chief Barnadino Rafael, a man widely regarded as the mastermind behind the brutal security crackdown (he denies any wrongdoing), and replacing him with someone who “respects human rights.”

Analyst and investigative journalist Luis Nhanchote told the BBC that before Chapo can tackle the issues like crime and corruption, “he has to calm down Mozambicans and do all in his power to restore peace in the country.”