Scientists are sounding the alarm on free-living amoebae, an often-overlooked group of pathogens that increasingly pose a growing risk to public health globally,.

In an article published in Biocontaminant and cited by SciTechDaily, researchers detail how climate change, deteriorating water infrastructure and limited systems for monitoring and detecting are fuelling the growing threat from these pathogens.

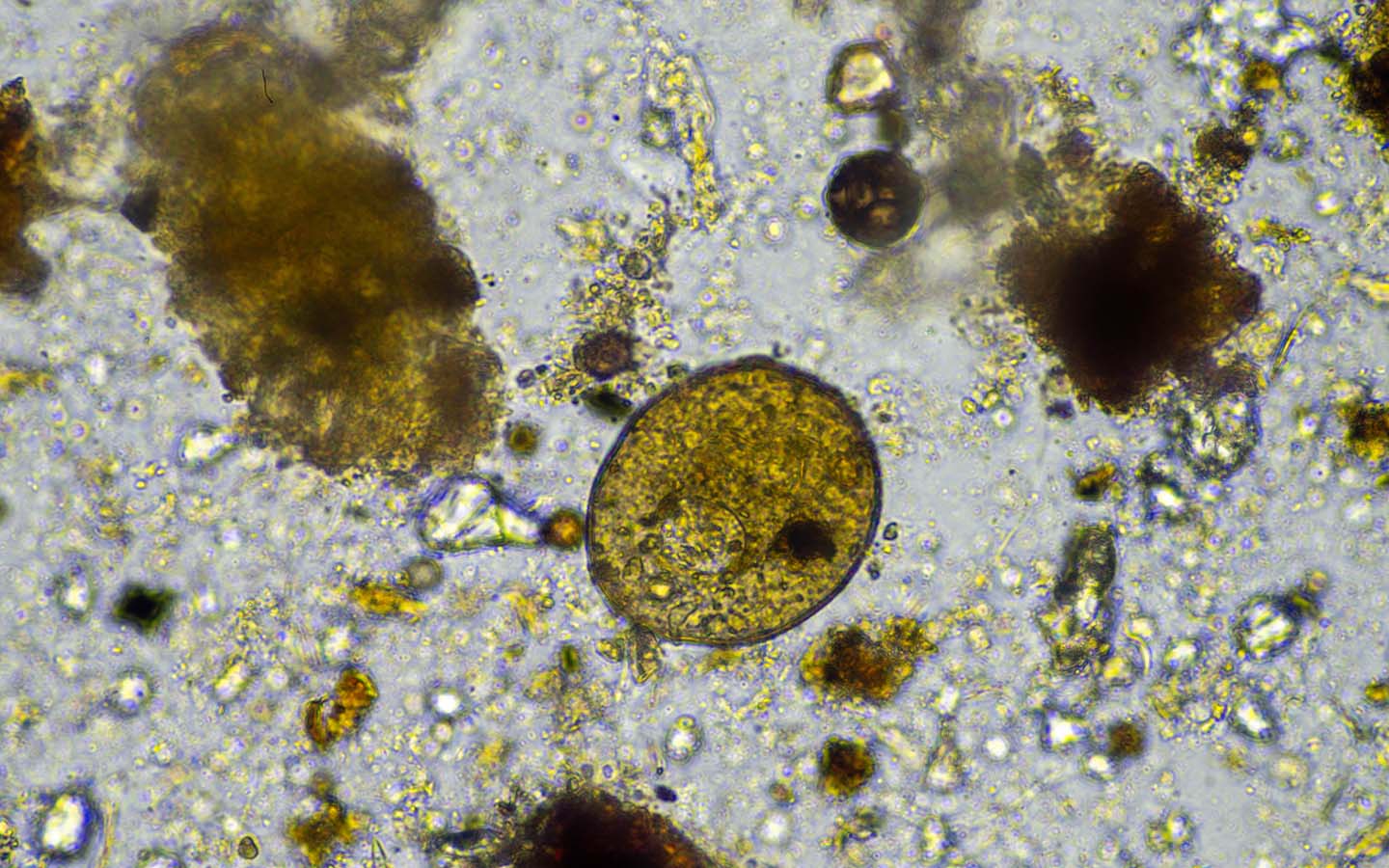

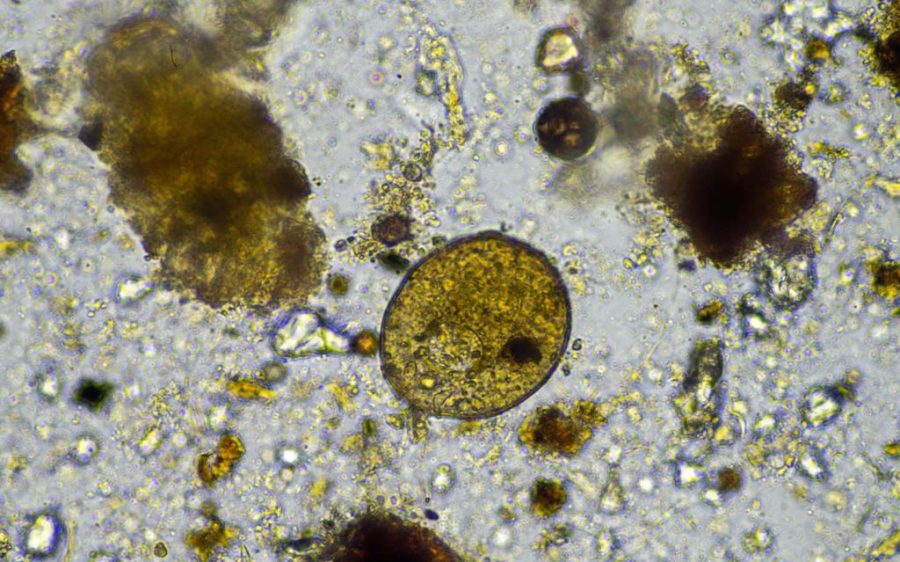

Amoebae are single-celled organisms living in water and soil where they serve as vital decomposers, feeding on bacteria, algae, plant cells and microscopic protozoa. While most are harmless to humans, a small number of amoebae species like Naegleria fowleri, also known as the ‘brain-eating amoeba’, and the Acanthamoeba genus are capable of triggering severe disease.

“What makes these organisms particularly dangerous is their ability to survive conditions that kill many other microbes,” corresponding author Longfei Shu of Sun Yat-sen University, told press. “They can tolerate high temperatures, strong disinfectants like chlorine, and even live inside water distribution systems that people assume are safe.”

[See more: China’s top Covid expert says climate change could spark the next pandemic]

That resilience to standard water treatment approaches can also benefit other pathogens. Amoebae are known to shelter bacteria and viruses – including those that cause Legionnaire’s disease, chlamydia, tuberculosis, norovirus and adenovirus – from disinfection and increase their environmental persistence. This ‘Trojan horse’ function can even contribute to the spread of antimicrobial resistance among pathogens.

As climate changes fuels the spread of heat-loving amoebae into new environments, the authors advocate for a One Health approach that connects human health, environmental science and water management.

They emphasise the need for enhanced surveillance, rapid diagnostics and targeted environmental interventions, as well as greater education to facilitate effective risk management and outbreak prevention.

“Amoebae are not just a medical issue or an environmental issue,” Shu said. “They sit at the intersection of both, and addressing them requires integrated solutions that protect public health at its source.”