For a city of its size, Macao has done exceptionally well in the competitive sport of wushu. One needs to look no further than the 19th Asian Games in Hangzhou last year, which saw the SAR take home six medals, four of which originated from wushu events. The city’s first and only gold prize during the competition that year also came from wushu athlete Li Yi, who was crowned the champion in one of the women’s disciplines. Macao’s only other two gold medals at previous Asian Games were similarly won by wushu practitioners, Jia Rui and Huang Junhua, in 2010 and 2018 respectively.

For the uninitiated, wushu – literally “martial technique” – is a type of martial arts display (but occasionally a contact sport) based on several Chinese fighting methods. The establishment of the International Wushu Federation in 1990 saw it become a modern codified sport, but its origins can be traced back several thousand years.

In comparison to Macao, larger regional neighbours such as Singapore and Hong Kong have fared less successfully at the Asian Games, with the former never having won a single gold medal for wushu and the latter still missing the top prize in any of the male wushu events. Even on the international stage, Macao has performed spectacularly well, garnering 11 medals at the 2023 World Wushu Championship in Dallas, US. The total was just four shy of the champion, mainland China, which has a vastly bigger talent pool to draw on.

[See more: 10 questions for Macao’s wushu gold medallist Li Yi]

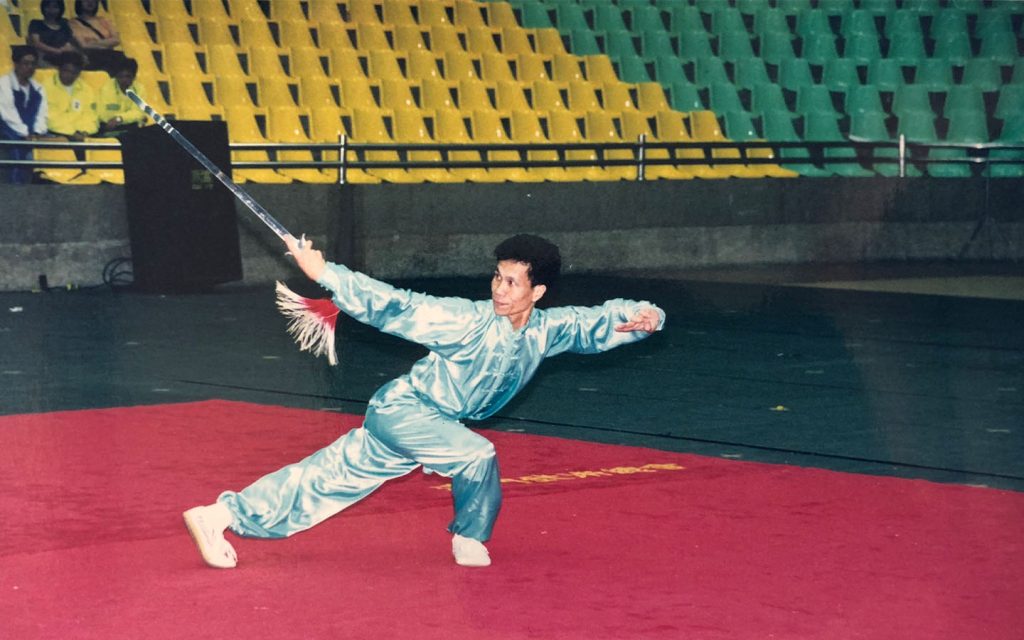

Locally, wushu is in a league of its own. Leong Chong Leng is one of the vice presidents of the Wushu General Association of Macau (WGAM) and a former wushu champion who represented the city during the 1980s and 1990s and now works as a coach. He notes that “Macao has 57 sport associations, but if we’re talking about taking part in Asian and World competitions, our [Wushu association’s] results are the best. This is recognised by everyone.”

Of course, Macao’s success in wushu didn’t happen overnight, but rather came about gradually through a combination of factors, including the city’s rich martial arts culture and the establishment of the WGAM itself.

Macao’s wushu history in a nutshell

Wushu began to take shape over the course of the 20th century. The development of organisations such as the Shanghai Jing Wu Physical Association and the inaugural Chinese National Wushu Games in Shanghai in the early part of the century helped to set the stage for the eventual codification and modernisation of traditional Chinese martial arts.

As a traditional practice, however, wushu has existed for thousands of years, with the International Wushu Federation believing that its genesis can be linked all the way back to the Bronze Age (3000 to 1200 BC).

Records indicate that martial arts gained a foothold in Macao during the latter part of the Qing Dynasty (circa 1644 to 1912) and early Republican era (circa 1912 to 1928). However, it was not until the 1930s that the development of wushu took off, with the Japanese invasion of China resulting in an influx of mainland Chinese wushu practitioners arriving in the city as refugees. They soon began to establish schools.

Among the many notable instructors who have left their mark on wushu in Macao are Chiu Chuk Kai, a master of the “praying mantis” style of martial arts; Man Chong Kong, a practitioner of Choy Li Fut, which was one of the most prevalent styles of wushu in Macao; and Lei Man Iam, a teacher of Chen-style tai chi.

[See more: Wushu star Li Yi is being honoured with a Silver Lotus medal]

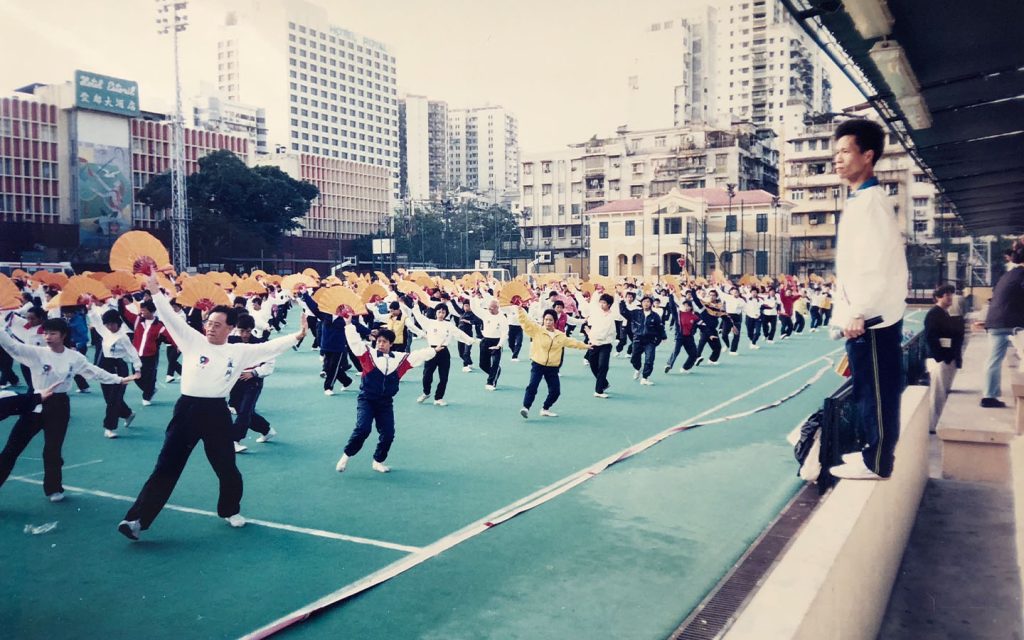

In years past, it had been customary for the different practitioners and their institutions to gather for the annual National Day Celebration (1 October). They held them at Cinema Alegria, or the Campo dos Operários (a sports ground that once occupied the land where the Grand Lisboa now stands), or the old Tap Seac Football Ground (which was replaced with Tap Seac Square in 2007). However, they were, for decades, without a formal body to coordinate wushu and represent the martial arts community as a whole.

This all changed in 1982 when Ho Yin, a prominent local businessman and the father of Macao’s first Chief Executive, Edmund Ho, decided to establish a wushu general association that would serve as a uniting force for the city’s martial arts world.

“His motive was that the martial arts world had always been a patriotic community” Leong explains By uniting them, “they would be able to support the nation in times of need.”

As fate would have it, Ho would never live to see the founding of his association, as he fell gravely ill after only two preparatory committee meetings. He subsequently passed away in 1983, putting the project on hold. In the years that followed, his son would take up the mantle after being informed by one of his father’s secretaries, Choi Tong Hoi, of the senior Ho’s wish. The younger Ho’s efforts culminated in the formation of the WGAM on 28 June 1988.

Training Macao’s wushu champions

With 118 affiliated organisations and close to 10,000 members, the WGAM plays an indispensable role in cultivating the high calibre athletes who have helped the city make a name for itself in competitive wushu.

According to Leong, the association holds a number of regular competitions each year, including the Macao Wushu Championship and the Macau Junior Wushu Championship, which are the main events used to recruit members of the Macao senior and junior wushu teams.

[See more: ‘I’d like to show the world that there is a Macao athlete called Angela Wong’]

While earning gold in these championships will certainly put an athlete under consideration for the team, the WGAM vice president points out that it does not guarantee automatic entry, as the organisation also considers a candidate’s potential for development, even if they did not achieve the best results during the competition.

For those who do make the cut, the training is rigorous, with Leong admitting that “the hours are very long.” He notes that the athletes are required to train everyday for three hours between 6 pm and 9 pm, year round on every day except Sundays. Despite the intensity of the program, the former martial artist says that it has yielded the good results that Macao has seen in competitive wushu.

Time off is rarely given. “As soon as you take a holiday, it will affect our progress because our sport requires cumulative training,” Leong says. “If you don’t train all the time, the physical gains from your earlier training will disappear. That’s why our management style is quite strict.”

[See more: Here’s where to learn Wushu in Macao]

Another important reason for the success of Macao’s wushu athletes is the fact that the WGAM frequently provides them with the opportunity to train with some of the best wushu teams in mainland China. “Sometimes we train in Beijing, Fujian and the different provinces,” Leong says. “We go and do short term training in whichever place has a higher level of wushu [mastery], especially during the summer.”

Leong acknowledges that none of this would be possible without the support of the SAR government, which covers the expenses required for sending up to 30 athletes for such training. “If this wasn’t the case, it would be very difficult [for us],” says Leong, “because how can you not cover food and accommodation costs and have parents and students pay out of their own pockets?”

The government has given the association’s junior and senior martial artists access to its Athlete Training and Development Centre where they can train using top class facilities and equipment. The Sports Bureau has also supported the development of wushu in the city by collaborating with the WGAM to establish the Macau Wushu Youth Academy, which has been training the SAR’s next generation of wushu talent since 2007.

All of this is a far cry from the way wushu was perceived when Leong first immigrated to Macao from Guangzhou back in 1978. At the time, he notes that parents would discourage their children from taking up martial arts due to its association with fights, turf wars and the triads.

In the decades since, the WGAM has completely revamped the image of wushu in the city by stressing the importance of wude (武德) or the martial arts code of conduct, in addition to advertising the success of its athletes and popularising the sport among all ages. The work of the organisation, however, is far from complete, with Leong pointing out that they are not only looking to constantly develop the wushu professionally in Macao, but also wushu for the masses, as practising wushu disciplines such as tai chi can be of benefit to one’s health.

Leong, however, has a far bigger dream. “I hope that wushu will enter the Olympics Games [as an official sport],” he says, echoing the aspirations of many wushu practitioners. He may get his wish, as the Olympic Committee will deliberate the sport’s viability in the Olympics after its debut in the Dakar 2026 Youth Olympics Games. If all goes well, the sport of wushu could be bound for even greater glory.

Correction appended, 22 May: This article has been edited to clarify the dates of the Qing Dynasty and to reflect Macao’s Olympic status.