Ung Vai Meng first discovered Chinese ancestor portraits in Macao in 1997. He was walking down Rua de São Paulo by the Ruins of St Paul when an antique shop caught his eye. An ancestor portrait in the shop instantly captivated Ung.

As a painter himself, Ung has a deep appreciation for precision and imagery, motifs and colours. And when he saw the portrait, he knew it was special. “They are beautiful, especially the portraits of children at home,” he says. “I returned to the antique shops from time to time and gazed at the portraits. But I couldn’t find any books on them.”

That begged the question: Why isn’t anyone studying these paintings? Ung seized the opportunity to become one of the foremost experts in Chinese ancestral portraiture. And 20 years later, he’s uncovered many surprising discoveries, tracked down lost works and shed light on the genre’s symbolism and colour theory. “As I have gathered a lot of information, I felt obliged to put them together for future scholars,” he says.

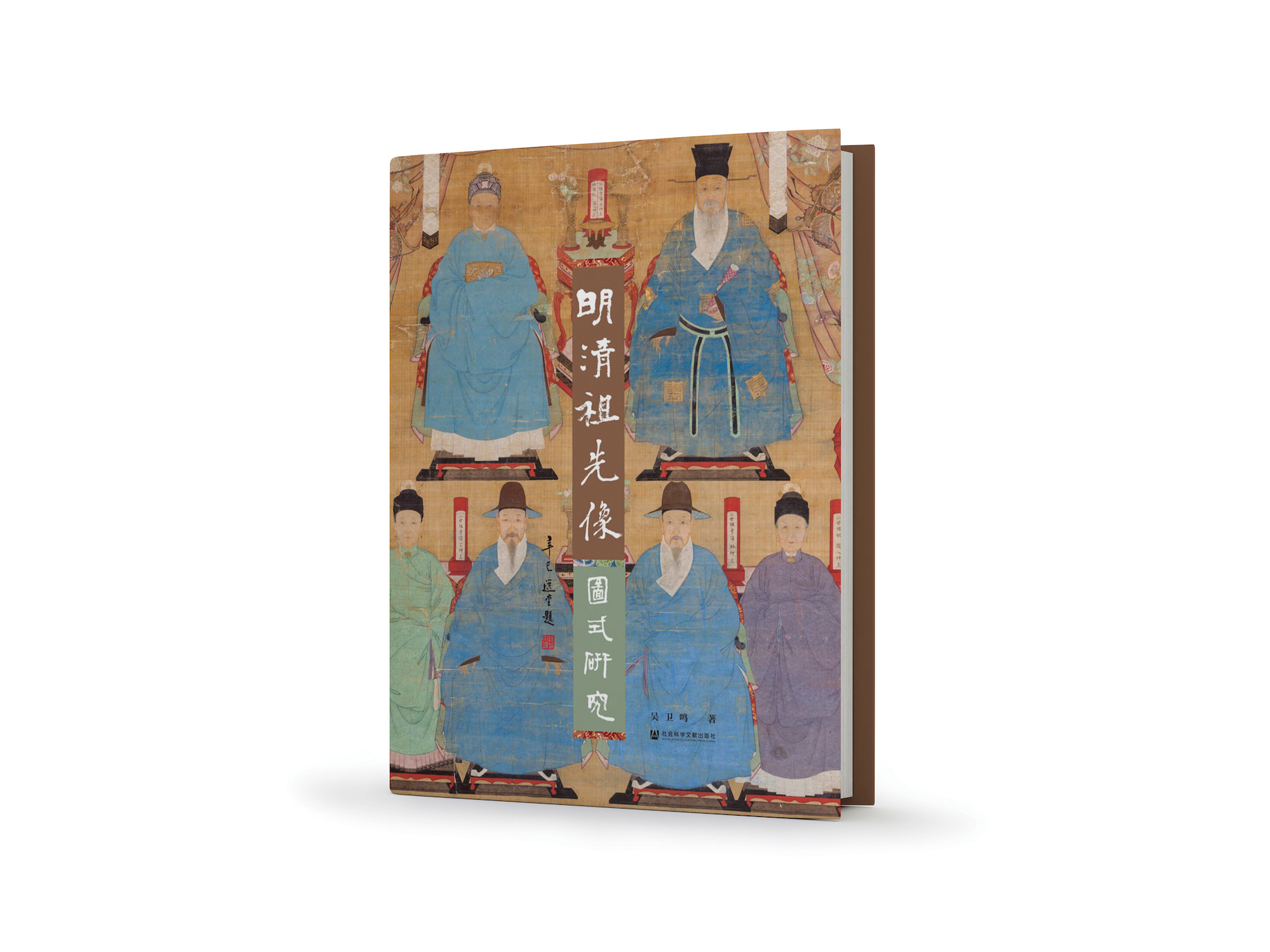

His extensive research informed Ung’s definitive book, Ancestor Portraits in the Ming and Qing Dynasties (《明清祖先像圖式研究》), which was published in Chinese in June 2020. Not only does the 256-page tome showcase many examples of Chinese ancestor portraits but it also digs deep into art theory, culture, context, techniques, symbols and motifs.

“I had a lot of questions and tried to get the answers from the paintings,” says Ung. “The portraits also tried to tell me many tales.”

Searching for answers

As the former director of the President of Cultural Affairs Bureau and Macao Museum of Arts (MAM), the 64-year-old is no stranger to the art world. He studied sketching and watercolours under the late respected painter Kam Cheong Ling and earned a master’s in traditional Chinese painting theory at the Guangzhou Academy of Fine Arts in 2002.

“I started researching ancestor portraits during my master’s because I had so many questions: ‘Why are the female ancestors’ feet covered? Why are male ancestors dressed in Qing-dynasty robes, but the wives are in Ming-dynasty styles? Why are the women dressed in different colours?’” he recalls.

He learned more about the genre from influential art dealer Zhan Qing He and then went on to earn a PhD in art history at the Chinese Academy of Art in 2010. All the while, he searched for answers to his questions about Chinese ancestral paintings.

Unlike many traditional styles of Chinese paintings, which focus on landscapes and flowers, the portraits depict realistic scenes and people. The style can be traced to the Ming dynasty (1368-1644), when China experienced an economic boom, and the arts flourished. During this era, Italian Jesuit painters visited the mainland, bringing many techniques that influenced Chinese painting.

When the Manchu conquered the country and established the Qing dynasty, which ran from 1644 to 1912, the new empire invited further cultural exchange between East and West. Most notably, photography emerged, which Ung believes contributed to the realism seen in Chinese ancestor portraits.

A form of filial piety

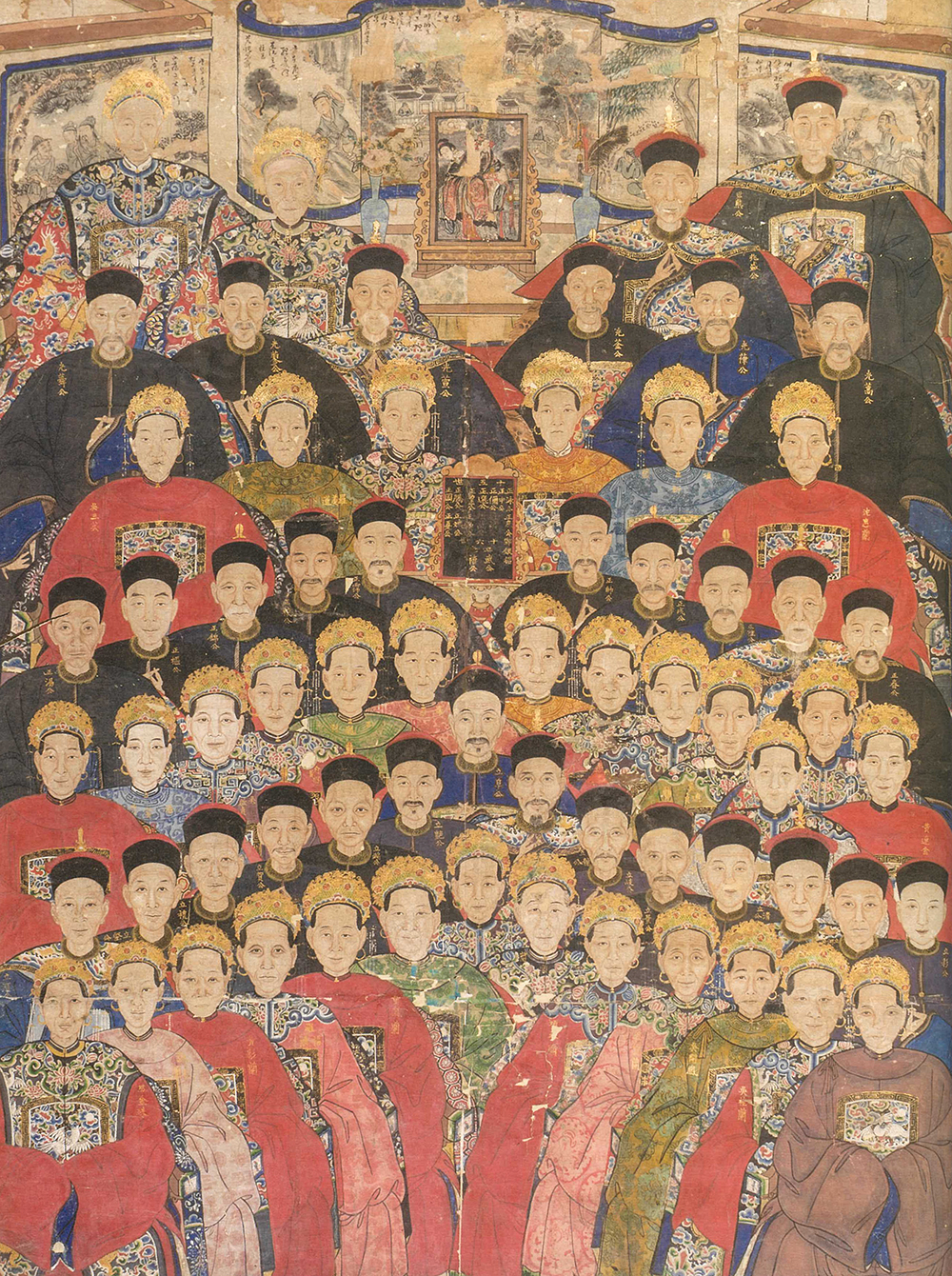

Ancestral portraits soon became a symbolic gesture of filial piety. Wealthy families would display the paintings at home to bless their ancestors and descendants or showcase family portraits in ancestral halls to mark occasions like the anniversary of an ancestor’s birth and the Qingming festival.

That’s why the first stop on Ung’s many research trips to China was usually an ancestral hall. “I started with Fujian province where many buildings were established for worship in their Hakka villages, such as tulou [an enclosed earthen structure with an ancestral hall, built to house multiple clan families] and Hakka houses,” he recalls. “In rituals, ancestor portraits play a key role.”

During the course of his research, Ung visited more than 300 ancestral halls and took photos of portraits he found along the way. If he came across an extraordinary portrait, he often bought it for his collection. “I tried to collect some special portraits,” Ung says, adding that each cost anywhere from a few thousand to MOP 20,000. “If I missed the chance, I feared I wouldn’t be able to find them again.”

His travels took him through numerous Chinese provinces, including Liaoning, Shandong, Shangxi, Guizhou, Sichuan, Hubei, Yunnan, Guangdong and Fujian. “I backpacked through cities and the countryside to explore museums, galleries, antique markets, villages, and ancestral halls [in search of the portraits],” he says. “My journey was enriching, not only for my research but also for my life.”

After the fall of the Qing dynasty – when many Chinese artworks were stolen or exported – these portraits began appearing in antique shops, museums and art galleries in Western countries.

To better understand the artform’s movements, Ung spoke to various experts about the genre’s historical and cultural context. “I wanted to explore the stories and facts about these ancestor portraits from multiple angles,” he says. Ung also visited museums and galleries in four Western countries, including the British Museum and the Victoria and Albert Museum in the UK, the Royal Ontario Museum in Canada, the National Museum in Prague and the Freer Gallery of Art in the US.

Decoding ancestral portraits

Ung’s book is packed with examples, photos and interviews with scholars and art dealers, which help to shed light on the meaning behind the paintings and learn about the subjects. As one example, the book’s opening photo – a beautifully detailed group portrait of a man sitting above two women – is full of symbolism. The dignified trio dons splendid costumes and highly realistic expressions.

“This portrait is fascinating. To draw a face in three dimensions – it requires light and shadow, which represent yang and yin in Chinese cosmology,” he explains. “Yin suggests death; yang, life.”

In the old days, he continues, Chinese society associated shadows with death. “After the cultural exchange with the West and the introduction of photography during the late Qing dynasty, people started changing their minds about the application of light and shadow.”

According to Ung, the costumes and accessories also carry symbolism. In the Qing dynasty, officials were assigned a social and political ranking with corresponding clothing, colours and motifs.

Conveying women’s ranks

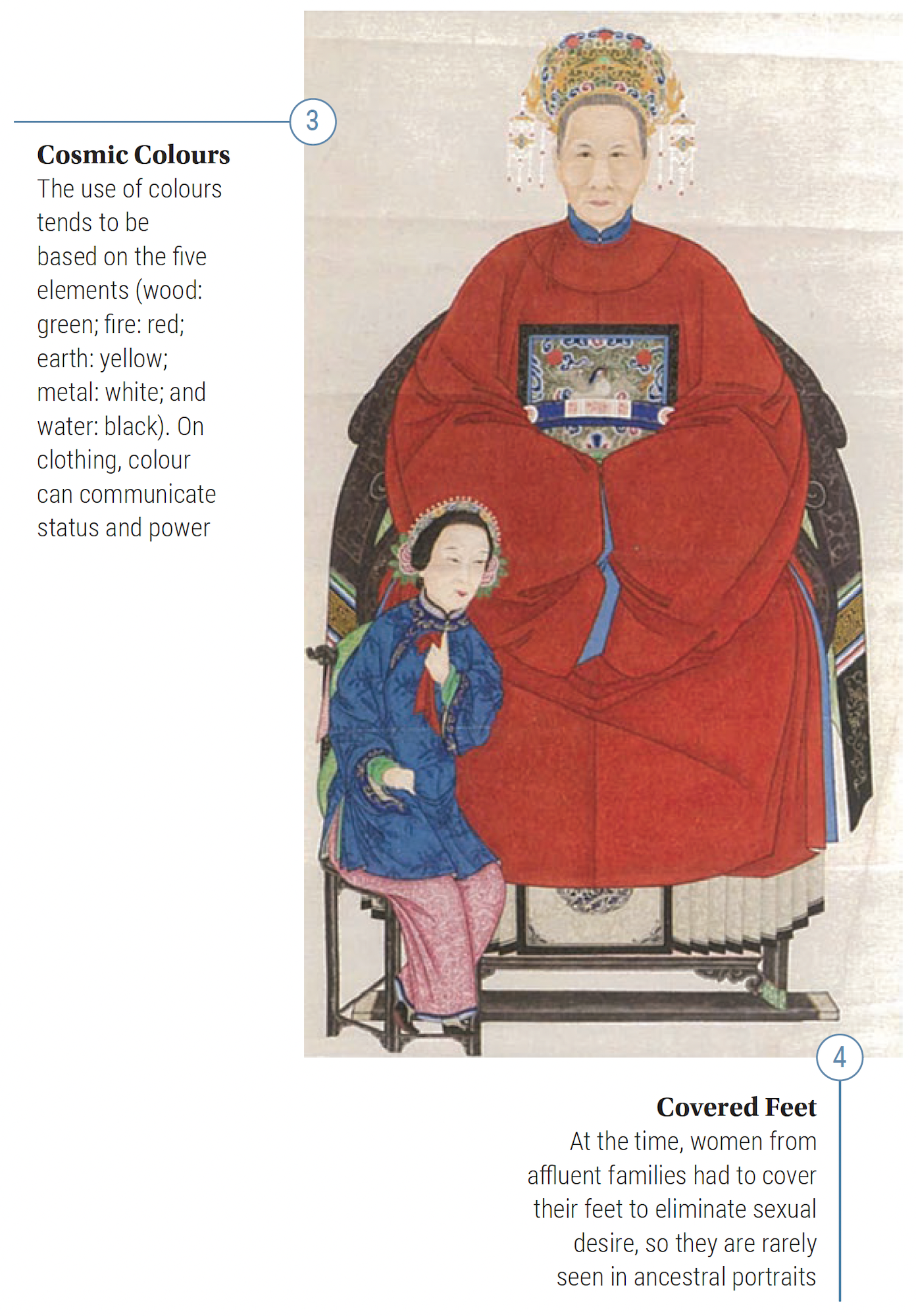

Another illustrated portrait in the book sheds light on the use of colour in Chinese portraiture. The painting depicts two women: one sits in a red robe on a quanyi (an armchair with a rounded back) with a significantly smaller woman standing to her right.

The colour, gestures, proportions and positions impart information about the women’s ranks. “In Chinese paintings, green, red, yellow, white, and black are the main colours,” explains Ung, adding they align with the five Chinese elements. In the image pictured above, the woman in red is the wife, while the smaller woman wearing pink trousers is her husband’s concubine.

“Pink is a mixture of red and white, so it is a secondary colour, used to show her lower rank.” In addition, the wife’s position on the left symbolizes superiority. “In many ancestor group portraits, the superior ancestor always lines from their left to right,” adds Ung.

He also draws attention to the wife’s covered feet. “In old times, women from affluent families had their feet bound, while working women didn’t,” he notes. “In these portraits, the female ancestors’ feet are covered to [eliminate] sexual desire. Once a woman was married, she stayed at home and was hardly seen by others.”

A link to our ancestors

Ancestors immortalised in Chinese ancestral portraiture often hold a steady, intense gaze that feels like they’re staring directly at the viewer. That’s not a coincidence, says Ung: “Ancestors usually sit in a quanyi chair and face their worshiping descendants. The subjects look back at the viewers – it’s a communication between ancestors and their descendants.”

The position also carries religious symbolism, while the type of chair speaks to Chinese cosmology. “The quanyi chair is deliberate. It makes the subject look dignified, almost towering, while the round back and rectangular footrest demonstrate the Chinese concept of ‘round heaven and square earth,’” adds Ung. “Their upright sitting positions are like those of Buddha. Ancestor portraits carry three significant [qualities]: communication, dignity and religion.”

Another highlight of Ung’s book is a 20th-century group portrait depicting a man wearing a modern military uniform and badge of honour. He’s seated in front of other family members dressed in ancient clothing.

“I’ve done a lot of research on that badge. It shows that the man fought and died in the Korean War, resisting the US aggression and aiding Korea,” says Ung. “While he is not dressed in ancient clothing, the purpose of the painting – remembering one’s forebears – still remains.”

While these portraits were once privately worshipped to recollect a family’s beloved and deceased ancestors, Ung hopes his research will raise more awareness about this unique Chinese art genre with other academics, scholars and the wider community.

“They have a rich cultural context and unique artistic values,” says Ung. “I hope my research can fill in the blanks. My next dream is to introduce these portraits to the Western world.”