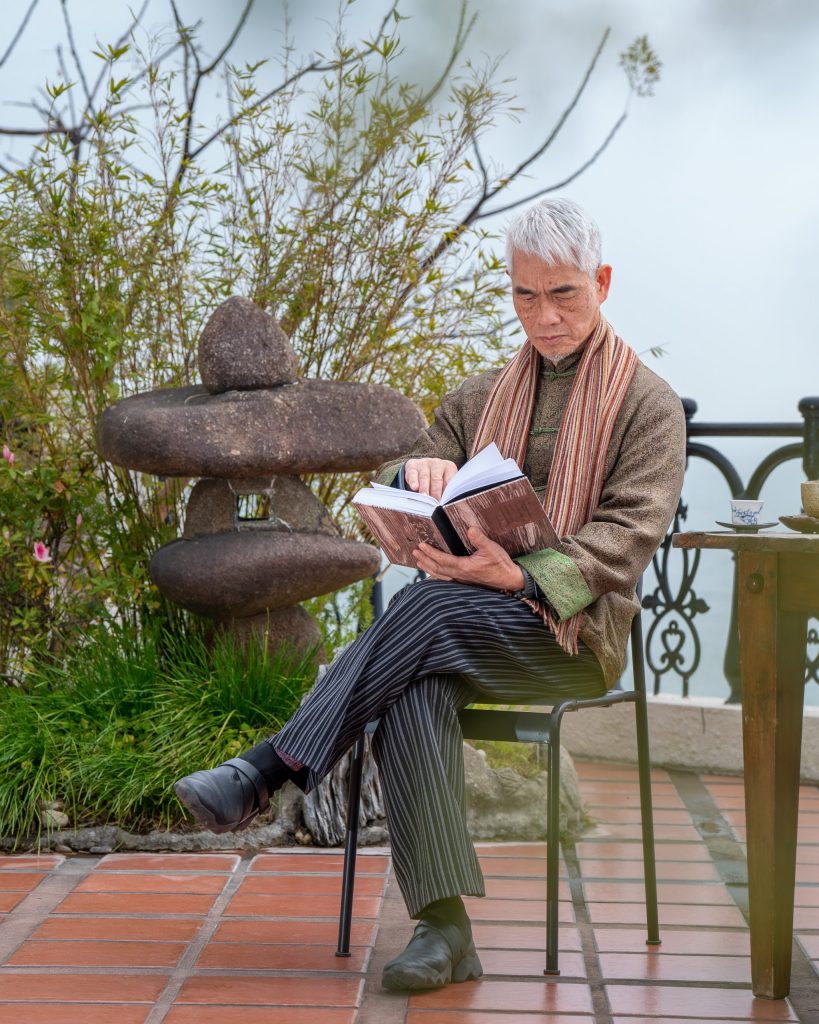

Lo Heng Kong rhythmically unravels a piece of turquoise fabric on the floor. Instead of making tea at a table, as is tradition, he kneels on the floor to be closer to nature.

He edges his knees onto a cushion, then arranges a large kettle, delicate teacups, a ladle and a bouquet of pink blossoms across the fabric. As if he is painting, the fabric becomes his canvas. All the while, the Macao Chinese Orchestra plays classical Chinese music in the background.

This unique tea ceremony was designed by Lo, a local tea master and educator, to celebrate the drink’s history in Macao, encourage its appreciation and elevate the ritual into performance art. “Tea is not only for drinking,” he explains.

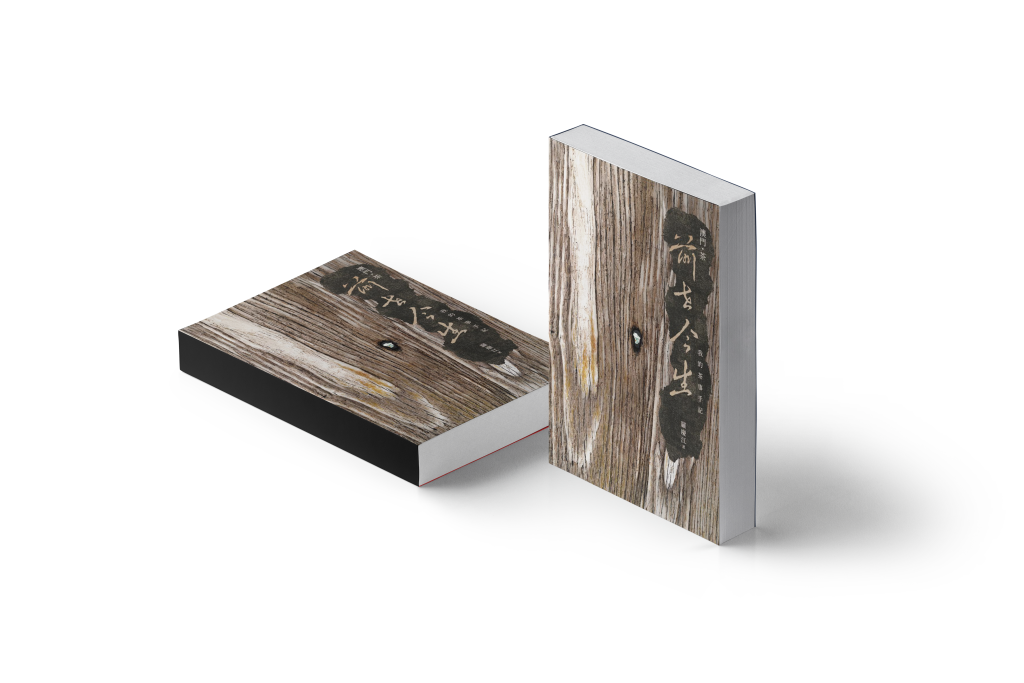

In 2020, he wrote about it in his book, Tea Ceremony Setting and its Designs. In the process, the 68-year-old discovered that many people do not know about Macao’s tea culture, let alone his new approach. This realisation inspired him to produce another book: My Notes on Tea: The Past and Present of Tea in Macao.

Part memoir, part historical record, Lo’s second book, published in 2021, feels like an archaeological dig. He often attempts to dust away misconceptions and unveil the truth about tea, from its Chinese origins to its heydays in Macao. It is also the culmination of his life’s work: a record of the past and a resource for future generations.

Macao’s foremost tea expert

Lo is well-positioned to tackle such a broad topic. He is an honorary committee member of the China International Tea Culture Institute, an honorary researcher of Ningbo East Asian Tea Culture Research Centre and a consultant of the Hebei Tea Culture Association. In 2009, he was bestowed with Macao’s honorary title of merit for his devotion to society.

He frequently gives lectures and workshops in local secondary schools and higher education institutes. He has also travelled extensively, taking part in seminars across Asia and consulting for tea associations in mainland China.

None of this would have been possible had he not left his career in interior design in 1997 to embark on a lifelong journey devoted to tea.

That same year, Lo opened Chun Yu Fang (meaning ‘Workshop of Spring Rain’) in Taipa. Here, enthusiasts could learn about tea appreciation, savour the drinking experience and purchase items, some he made himself – Lo hand-makes wooden tools and designs porcelain teacups, kettles and scoops, which he then has made in a Chinese kiln.

In 2000, he founded the Chinese Teaism Association of Macao and delved deeper into teaching and research. “I love tea, as well as teaching the art of tea,” he says. “Instead of having only a few lessons, I hoped my students could sustain their studies.”

Seven years later, he moved Chun Yu Fang into the green hinterlands of Coloane and changed its name to Chun Yu Fang Tea House, realising one of his dreams. “As I buried myself in writing and research, and [would be] getting older, I hoped to find a proper spot for teaching and research.”

Tea takes root

Lo’s ambitious new book is the culmination of these experiences, as well as a more personal history with tea.

Designed by his student, Zen Wong, the cover features an illustration of a broken wooden door with a keyhole in the middle. Through the hole, readers can see a tiny porcelain teacup – the same used at the famed Kun Nam Tea House, which operated from 1953 to 1996 on Rua de Cinco de Outubro.

For Lo, this delicate teacup (made in Jingdezhen, a ceramics manufacturing hub in Jiangxi province) overflows with memories. He recalls visiting Kun Nam Tea House with his father, a tea house manager with a deep knowledge of the drink.

“He was a busy man. Life was tough back then, so I couldn’t bring myself to ask him questions,” says Lo. “When writing the book, I really regretted not finding out more about tea from him.”

But Lo’s insights prove more than sufficient. My Notes on Tea provides a deep dive for beginners and connoisseurs alike. Divided into four chapters, the book covers a lot of ground, from tea’s beginnings in China to Lo’s memories in Macao and insights into tea ceremonies and tools.

Through a mix of research and storytelling, Lo strives to trace tea’s footsteps through Macao and celebrate its traditions.

He also wants to debunk a pervasive misconception worldwide that tea culture originated in Japan. In fact, its roots stemmed from China.

“Many misunderstand that the art of tea originates from Japan,” he says, “so I decided to find the origin and present it [in the book].”

A bridge between two worlds

In Macao, the “golden age” of tea, as Lo calls it, ran from the mid-1500s to the mid-1800s, as the Portuguese settled and began trading in the territory.

The port in Guangzhou, then known as Canton, had been open for foreign trade since the 14th century. (It was also the only one open to foreign trade from 1757 to 1842.) Since Macao was located just 150 kilometres down the Pearl River, the city became an important entrepôt – a trans-shipment port where goods can be reloaded for the onward journey – for Chinese goods.

In his book, Lo explains that the Dutch and British ruled the tea trade in the early- to mid-17th century. But after the turbulent transition between the Ming and Qing dynasties in 1683, the Kangxi Emperor banned all foreign trade unless it went through Macao, giving the Portuguese an opportunity to satisfy the West’s growing demand for tea.

While the British would eventually monopolise the tea market following the treaty of Nanking in 1842, when the Qing dynasty reopened to foreign trade, Macao continued to play an essential role as an intermediary port.

The second golden age

Although trade slowed during the next century, Macao saw another “golden age” of tea in the 1940s and ‘60s.

During this period, tea house culture boomed. Famed tea houses – Lok Kok, Kun Nam and Iun Loi – dotted the historical Rua de Cinco de Outubro and the surrounding neighbourhood.

In his book, Lo explores this era by examining an order sheet from Va Mau tea shop. On the sheet, over 60 kinds of teas were available, something Lo believes demonstrates the city’s high standards at the time.

In the 1970s, however, these businesses started to decline as locals sought employment in the burgeoning textile and clothing industry and a wider variety of dining outlets – Western-style franchises, Chinese-style hot pot and seafood restaurants – emerged.

“A great number of tea houses began to close down to give way to urban development – the current site of Kun Nam is a hotel, and Iun Loi a supermarket,” says Lo, emotional about the loss. “Many have forgotten the thriving tea culture in Macao.”

Life starts with tea

A hefty 500 pages, the book took Lo about a year to write, a process that involved combing through research, photos and notes from business trips to mainland China, Japan, Taiwan and South Korea. Time, however, was a resource he had in abundance.

“Due to the pandemic, many of my lectures and workshops had to be put off. So I wrote like clockwork every day,” says Lo.

After years of teaching about and researching tea, the subject has become an integral part of Lo’s life. His teaching, research and books are all part of his mission to sustain local tea culture and inspire the next generation while expanding his well of expertise.

“When I wrote about Chun Yu Fang, a wave of memories came over me. I thought about the customers who spent their afternoons appreciating tea here. I was sometimes angry as our culture had been underestimated,” says Lo. “However, whenever I reminisced about how I have grown professionally and became recognised, I felt grateful.”

Find Lo’s books (available in Chinese only) at local bookstores: Macau Plaza, Universal Gallery & Bookstore and Elite Book Store.

This article has been produced in collaboration with the Macao Magazine. The full story can be read in their April 2022 #69 issue.