Throughout the Han Dynasty (202 BC – 220 CE), Chinese calligraphy scripts were widely used in letters, seals, official documents and paintings. But calligraphy is much more than ribbons of ink on paper. Akin to poetry, calligraphy is one of the most revered art forms in Chinese culture, with each careful stroke expressing the calligrapher’s unique personality and perspective.

As pens, paper, and later computers, eventually overtook brushes and ink, calligraphy has only become a rarer and more valuable craft. Fewer and fewer people know how to master the five artistic scripts – seal, clerical, regular, semi-cursive and cursive – let alone manipulate traditional animal-haired brushes and inkstone to create beautiful brushstrokes.

But in Macao, one family is keeping the tradition alive for posterity. Father and son calligraphers Mok Wa Kei and Elvis Mok Hei Sai have followed different paths to master the artistic script. And while they honed their skills in different eras and environments, they share a passion for calligraphy that has inspired a new generation of talents.

Destined for greatness

Elvis was destined for a future with a brush in hand. Not only does his Chinese name pay homage to two legendary calligraphy figures – the “Sage of Calligraphy” Wang Xizi (303-361) and scholar Yu Shinan (558-638) – but his father passed on his raw talent.

“When I was studying at Choi Kou High School where my father taught,” he says, “I was expected to have a good hand because of my father.”

His 71-year-old father, Mok, is an award-winning calligrapher, whose career spans over four decades. Since childhood, Mok recalls being fascinated by his father’s talented hand before studying his uncle’s book, “Thousand Character Classic in Four Calligraphy Styles”, at the age of 11.

As a teenager, Mok made ends meet by juggling part-time jobs – he sold soft drinks at the Macau Canidrome Club and worked at garment factories. He paid for his own secondary school education while continuing to pursue the craft of calligraphy.

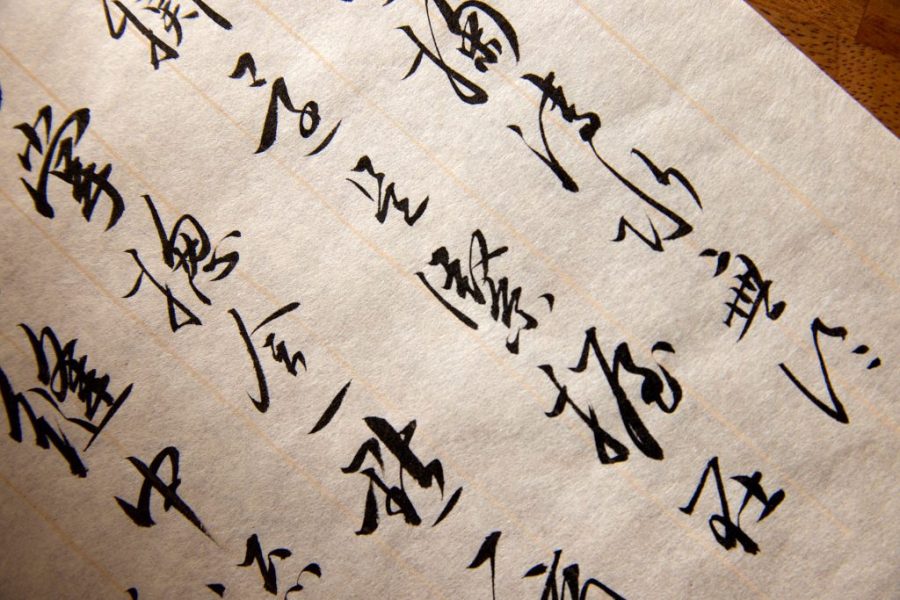

While studying for a bachelor’s in education, Mok took private lessons from renowned Macao calligrapher Lam Kan. Since Mok wanted to distinguish himself from many great calligraphers at that time, he chose the rarely practised, archaic “clerical script” and studied it under another master, Lau Tin Fuk.

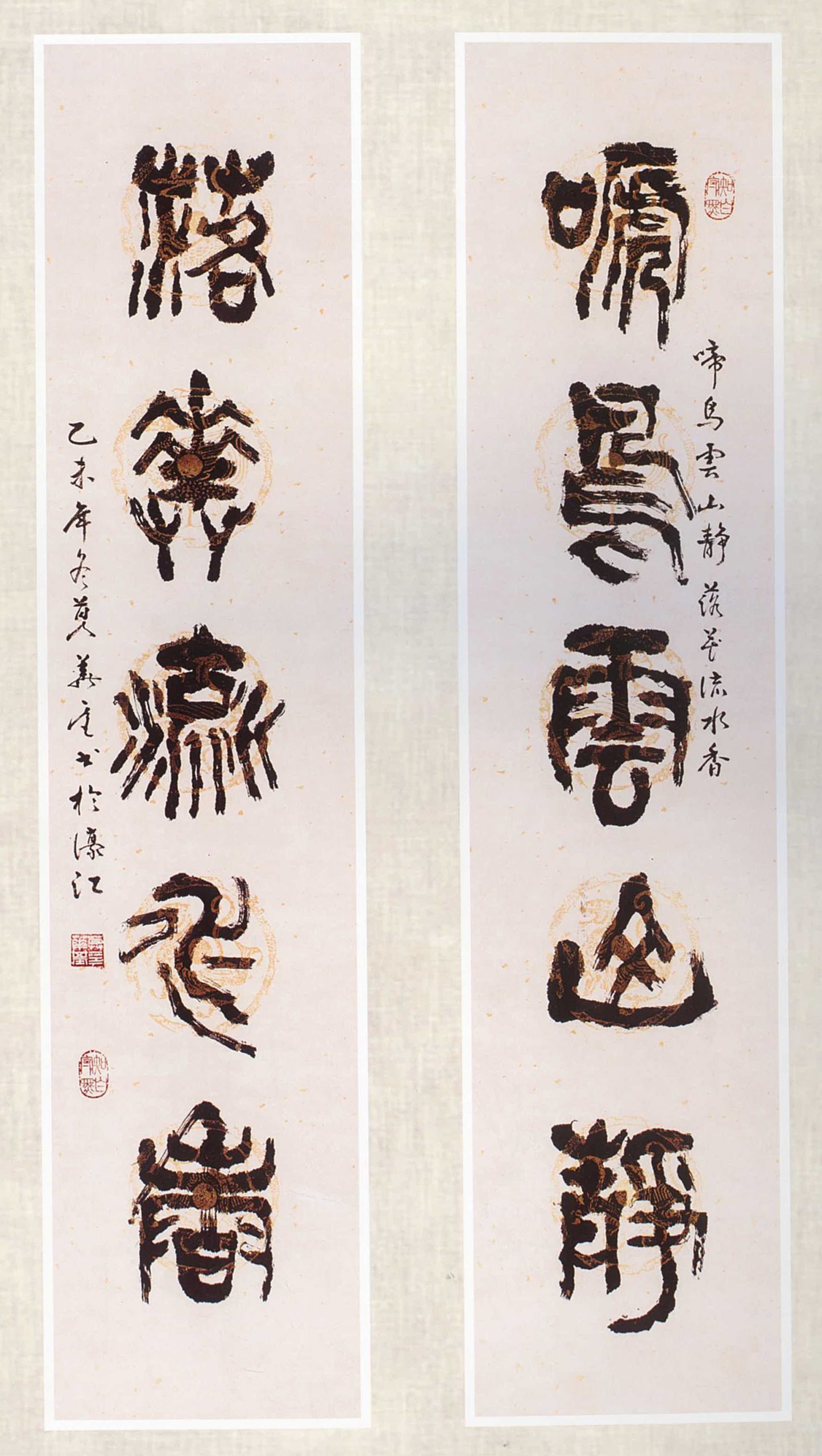

With this script as the foundation, Mok developed his own style in his 50s. It’s what he describes as a “slow script”, which enables him to “experience the magnificence within”. A decade later, in his 60s, Mok mastered another style, “seal script”, that is known for its symmetry and balance.

Decades later, Mok’s son also found his way to the art of calligraphy – albeit in his own time. Despite his pedigree, 39-year-old Elvis says he didn’t truly take an interest in the art form until after he graduated from secondary school in 2000.

The summer before Elvis started studying Chinese literature at the University of Macau, his father gave him a workbook of different calligraphy styles from various Chinese emperors. Suddenly, Elvis was hooked.

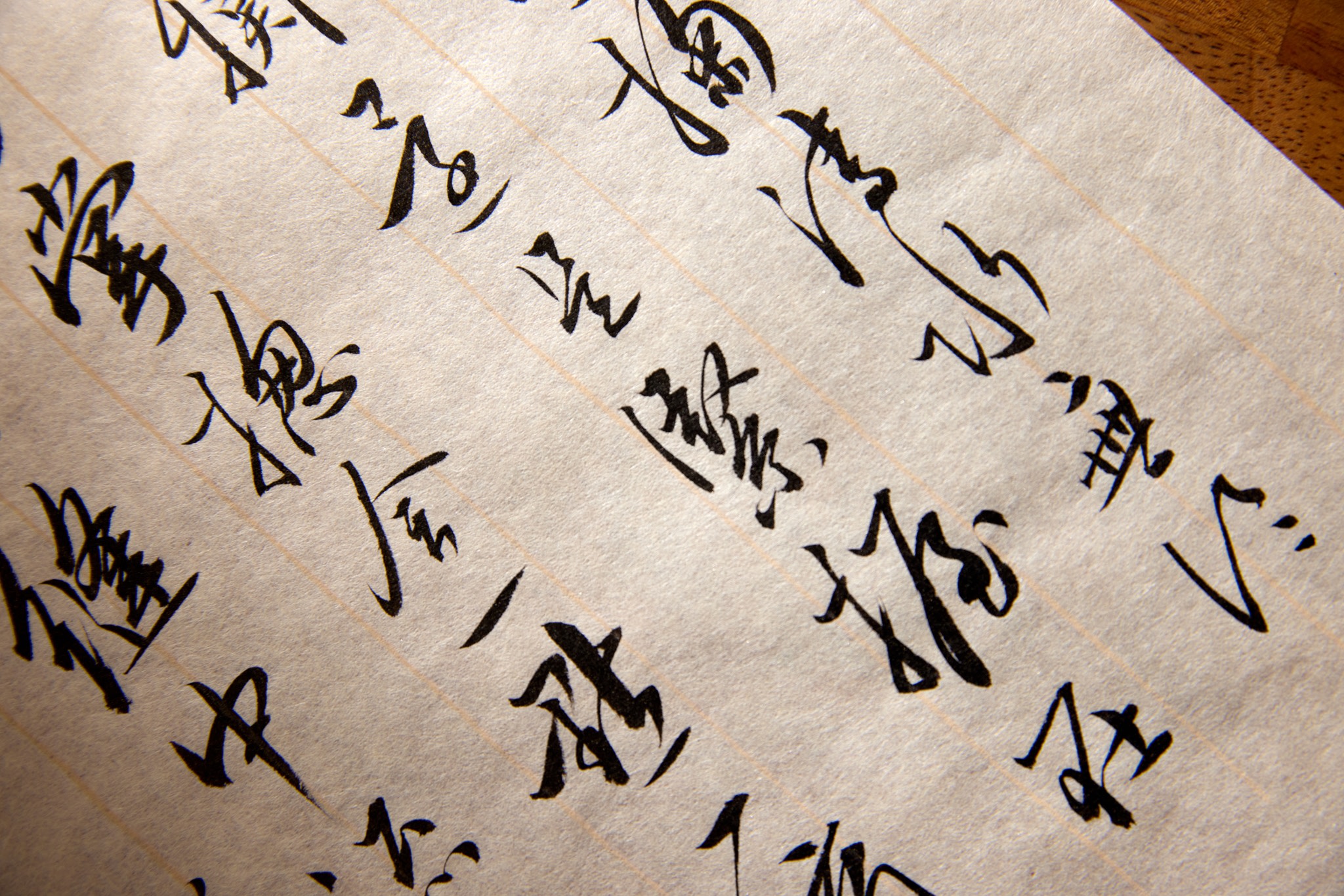

He fell in love with a style of brushwork known as “slender gold”, a legacy from Emperor Huizong of the Song Dynasty (960-279 CE), who was a poet, painter, calligrapher and musician. As its name suggests, the style is characterised by thin yet sharp brushstrokes produced in a light, spirited manner with firm turns and stops. While not literally gold, the elegant style is said to reflect the emperor’s refinement and attention to detail.

“Emperor Huizong’s goal was to inscribe gonbi paintings [a realistic style of Chinese painting with meticulous brushstrokes] with slender gold calligraphy,” says Elvis. This relatively rare style, he says, is ideal for crafting small characters – his speciality – because it calls for thinner, more delicate brushstrokes. While large characters communicate a sense of power, small letters evoke grace and refinement.

In addition to slender gold, Elvis immersed himself in various Chinese calligraphy styles during his university years, and eventually took part in exhibitions alongside more experienced calligraphers.

“In the next 10 to 20 years, my plan is to elevate my skills to the upper levels of calligraphy art.” Traditionally, to be a top-level artist, calligraphers must master five styles of scripts: seal, clerical, regular, semi-cursive and cursive. “Regular and semi-cursive scripts are also my forte – slender gold is considered to be a regular script,” adds Elvis.

Classic art, contemporary contexts

After university, Elvis taught Chinese literature in secondary schools for seven years, changing direction to explore his passion for calligraphy. In 2014, he became the artistic director of Tealosophy Tea Bar.

The Macao tea bar promotes calligraphy and Japanese tea culture, which is closely linked to the tea traditions of China’s Song Dynasty. As a nod to this historic connection, it is called “Bianjing”, the capital of the Song Dynasty, in Mandarin.

“Calligraphy plays an important role when it comes to a tea house’s atmosphere,” Elvis explains. “In Japanese tradition, for example, guests should appreciate the calligraphy works in a tea house before drinking the tea.”

Working with Tealosophy has influenced the way Elvis approaches calligraphy. In the past, Elvis practised calligraphy by copying works by masters. But now, he thinks more deeply about the words, artwork and brushstrokes – and how they will be appreciated by guests.

“When you copy a master’s work, you learn his style by practising. But to me, calligraphy is more of a creative experiment. I now think about trying different compositions and styles and see what happens.”

As Tea Bar’s artistic director, Elvis designs and writes catalogues, menus and product packaging in his signature slender gold style. Although the Macao business relocated to Hong Kong in 2019, Elvis continues to work with them. He values the experience, particularly since he is deeply interested in Japanese tea traditions and Song Dynasty culture.

“Customers get curious about the calligraphy and ask who created it. This has helped me improve; I feel compelled to hurry up and finish my pieces so that more people could see them at the Tea Bar.”

In 2017, Elvis founded Hon Mak, an educational centre in Macao’s Rua de Francisco Xavier Pereira neighbourhood that provides various Chinese calligraphy and painting classes. The centre, which means “brush and ink” in English, provides calligraphy classes to students of all ages.

It was only natural that Elvis approached his father, a lifelong devotee to the craft and occasional educator, for guidance on the new venture. The calligraphy maestro joined his son’s venture as part of the father-son duo’s mission to encourage appreciation of the ancient practice.

Now in its fourth year, the centre is flourishing, and Elvis and his father have more time to hone their skills and study new styles of calligraphy. For any student striving to master the art, Mok shares advice that’s as pragmatic as it is poignant: “Follow the steps of your predecessors first, and then set yourself apart. An artist must have his or her own style.”