Duong Trung Duc is a Vietnamese chef who envisioned a future for himself in Macao back in the early 2000s, when the territory began its ascent as the gaming hub of Asia. “I could see Macao was about to offer a lot more opportunities,” the 62-year-old recalls. When Duong arrived in 2003, he says he “liked the city right away.”

While Duong is an economic migrant – seeking to better his circumstances abroad – he is also a refugee who fled Vietnam during and after the American war that ended in 1975. Duong’s family were so-called “boat people,” landing in Hong Kong before being relocated to France. It was only after this that he returned to Asia, opened a restaurant in Hong Kong, then moved to Macao. Duong had an advantage over many foreigners in the Special Administrative Region at the time: he’s a polyglot. Along with his native Vietnamese, he speaks Cantonese, Mandarin, English, French and basic Italian.

[See more: Are more Vietnamese workers the solution to Macao’s labour shortage?]

After people from the Philippines, Vietnamese form the second largest foreign community in Macao. Duong’s skills and experiences make him uniquely qualified to be this tight-knit community’s de facto leader. While he has always been willing to help newcomers from Vietnam get settled, he’s recently become president of a local Vietnamese association that works with the consulate in Hong Kong – which he does in addition to running his restaurant.

Before the Covid-19 pandemic, more than 15,000 Vietnamese non-resident workers lived in Macao. Now, even with the borders open, that number is about half. Most of the community are women, working as domestic helpers, with the next biggest cohort (less than a fifth) employed by the gaming industry. Several hundred Vietnamese-born people also hold Macao ID cards. Most adults do not speak Chinese or English.

Language aside, Vietnam and Macao have a lot in common (both, of course, share borders with mainland China). Confucianism, Taoism and Buddhism have played a leading role in shaping their cultures, and Lunar New Year is the most important festival celebrated in each place. Tet, as the holiday is called in Vietnam, is when families come together, lions dance and lucky money gets distributed – just as it is in Macao. The Mid-Autumn Festival (Tet Trung Thu in Vietnamese), and the festival’s signature mooncakes, are important in both cultures, too.

The places also share histories of foreign administration, though on different scales. Macao was administered by Portugal for more than 400 years. Vietnam was under French rule for less than a century – but long enough for the Europeans to leave their architectural and culinary legacies in the country, as they did in Macao. Many Vietnamese, especially those from the south, have connections with France. That includes Duong, who lived there for a number of years.

[See more: The number of migrant workers in Macao is nearing its pre-pandemic level]

The restaurant he and his wife run together is, in fact, named Pho Vietnam Paris. Located in NAPE, the eatery is a gathering point for local Vietnamese on weekends. Besides the eponymous noodle dish, the couple serve traditional favourites like rice-paper spring rolls and goi ga (a piquant chicken salad). Their food is a taste of home for Macao’s Vietnamese community.

Cooking his native cuisine food feels special for Duong, though he’s equally adept with Italian. His restaurant helps him maintain something the chef feels passionate about: Vietnam’s cultural identity. “I like promoting our fresh and healthy cuisine to the people of Macao,” the father of two teenage sons says. Duong also gets a kick out of meeting fellow Vietnamese people visiting the restaurant, who may need assistance with language or local bureaucracy. “I just want to help them when they are in difficult situations,” he explains.

Refugees and economic migrants

Duong and the wave of economic migrants who arrived in the early 2000s were not the first Vietnamese to live in Macao. Starting from 1975, Macao – then a Portuguese-administered territory – took in refugees fleeing the aftermath of the war fought by Vietnam against America.

These refugees were the boat people, and mainly hailed from the country’s south. Their first ports of call, after setting off from Vietnam’s coast in crowded, barely sea-worthy vessels, were other Southeast Asian nations, as well as Hong Kong (where Duong’s family landed) and Macao. Hundreds of thousands of boat people fled Vietnam, and many perished before reaching a safe harbour.

According to the United Nations, at least 7,100 Vietnamese refugees arrived in Macao between 1975 and 1995. Three refugee camps were set up to house the bulk of them – the Catholic Relief Services (CRS) operated the Ka Ho (the biggest) and Luís de Camões camps, while Caritas Macau ran one at Ilha Verde. To accommodate the overflow, two unofficial camps also operated: one near Ocean Gardens (it’s now home to the Scout Association of Macau) and a smaller camp in Areia Preta.

[See more: Life in the Ka Ho refugee camp in the 1970s and 1980s]

The refugees enjoyed freedom of movement in Macao, according to Caritas Macau Secretary-General Paul Pun, who worked at the Ilha Verde camp. They received pocket money, regular meals, education and medical care. Vietnamese refugees were also able to work in Macao, though for comparatively low wages.

For most of the boat people, Macao was just a temporary stop on their journey to a Western country. They waited until the UN secured them resettlement arrangements with countries like France, Canada, Australia and the US.

During the next decade, a second wave of Vietnamese started arriving. They sought to work and live in Macao longer-term, then return to Vietnam once they’d saved enough money. While Vietnam has one of the fastest growing economies in the world today, back then it was a low-income country offering few opportunities for its citizens. Macao was seen as a place where you could earn enough to lift both yourself and your family back in Vietnam out of poverty.

As Macao’s economy grew after the city’s handover to China, local people got richer. They could afford to hire domestic helpers, and Southeast Asia was the main market. As more integrated resorts sprouted up, venues needed more workers than Macao itself could provide. They started hiring non-residents, too, including some from Vietnam.

[See more: Meet the women fighting for a better deal for their fellow domestic helpers]

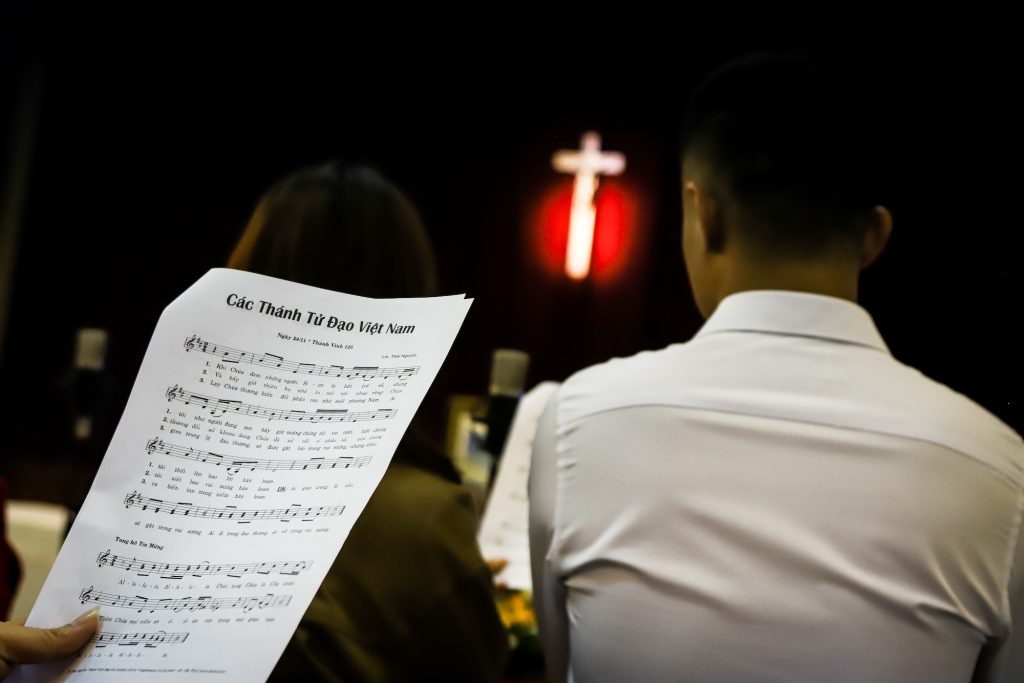

Macao’s Vietnamese population thus continued to grow for almost two decades. During this time, more Vietnamese restaurants opened and a Catholic congregation was set up to serve the increasing number of Vietnamese-speaking Catholics in the city.

Life for Macao’s Vietnamese during the pandemic

As it did the world over, Covid-19 had a devastating effect on Macao’s economy. Many businesses closed, meaning foreign workers lost their jobs and had to leave the city. Locals also lost their jobs, or had to live on reduced incomes. In some cases, they could no longer afford their domestic workers – who would then be laid off, too. “A lot of Vietnamese lost their jobs during the pandemic,” says Duong.

This led to Duong establishing the Overseas Vietnamese Association, in November 2020, at the request of the Vietnamese consulate in Hong Kong.

“I had to step up,” he explains. Unable to travel to Macao during the pandemic lockdown – and knowing the voluntary work Duong already did for Vietnamese migrant workers – consular officials asked Duong to be their unofficial representative. The new association was formally authorised by Vietnam’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs in 2021.

[See more: Thousands of Vietnamese stranded in Macao]

That’s how Duong started delivering consular services to Macao’s Vietnamese. At the height of the pandemic, he liaised with authorities in Macao and Hong Kong to charter flights for stranded Vietnamese – people who’d lost their jobs and couldn’t get back to Vietnam due to the lack of commercial flights at the time. He helped raise funds for those who couldn’t afford to pay, and handled a formidable mountain of paperwork.

The association also collaborated with charitable organisations. Father James Ho Ngo Lu Vien, who founded the Vietnamese Catholic congregation back in 2007, proved an essential partner in this task. The church helped raise funds and distribute food parcels containing the likes of instant noodles, rice, and eggs to about 300 Vietnamese migrant workers who’d lost their jobs.

“The parishioners and some priests stepped up and helped the migrant communities,” says Father James. “It was really touching to see people in such a difficult moment unite to help.”

Looking forward

Now that life is almost back to normal, Father James looks forward to organising activities for Macao’s remaining Vietnamese community – which currently numbers 7,600. “Before Covid, the church hosted many activities like barbeque, games and sports,” he recalls.

Duong and the Overseas Vietnamese Association have already held a number of events in the past few months. There was a shindig marking Vietnam’s national day, which falls on 2 September, an all-female badminton tournament in celebration of Vietnamese Women’s Day, and a football match between the local Vietnamese team and one made up of Macao players.

The association’s functions are open to everyone, Duong says. “Sometimes we also have joint events with the Filipino, Indonesian and the Myanmar communities, but I want all Macao people to come to our events. This way, others can learn more about the Vietnamese community.”

Its main objective, however, is to strengthen bonds within the community and individuals’ sense of cultural identity. Duong notes that this is especially important for families with mixed cultural backgrounds.

Mai Nguyen’s family is one of these. Nguyen, 40, moved from Vietnam to Macao in 2006, to work in a beauty parlour. The beautician could only speak her native tongue and a smattering of English, but had Vietnamese friends in the city who helped her settle in. She fell in love with a man from New Zealand, who works for an extreme sports and entertainment company in Macao. The couple married 11 years ago and Nguyen is now a stay-at-home mum raising their two girls. The whole family hold Macao permanent ID cards and Nguyen now speaks good English and Cantonese, along with some Mandarin.

She often brings her daughters – 11-year-old Ruby and 6-year-old Rosie – along to events hosted by the association. “It’s important for them to understand their identity, being half-Vietnamese,” she says.

[See more: Macao’s East-meets-West culture is its ‘greatest advantage’]

In this vein, Nguyen’s girls always wear beautiful ao dai (the Vietnamese national garment) during Lunar New Year festivities – by far the biggest holiday in Vietnam. Nguyen has also taught them to speak fluent Vietnamese. “I always talk to them in Vietnamese these days,” Nguyen says. “When we go back to Vietnam to visit our relatives, my daughters can communicate with them in Vietnamese.”

Nguyen says that after almost two decades in Macao, the city has become home. “I like the Macao lifestyle,” she enthuses. “Everything is so convenient. There is less traffic here, it doesn’t take long to travel from place to place, and Macao has a better quality of education for our children.”

But she still misses her homeland – especially authentic Vietnamese food, the ubiquity of ca phe sua da (the country’s specialty coffee served with condensed milk and ice), beautiful beaches and the vast tracts of wilderness. And her relatives, too, of course. Nguyen says that the Overseas Vietnamese Association helps her feel connected to Vietnam and her fellow Vietnamese.

“Every time I go to the events and meet other Vietnamese in Macao, I can see they are happy,” she says. “It makes me happy too.”