On a reclaimed tract of land southeast of Macao’s Cotai Strip, the remains of the former Ka Ho Refugee Camp are slowly being erased, lost to time’s inevitable march. The camp’s defunct administrative building in Coloane still stands, but the space now hosts the Centro de Formação Juvenil Dom Bosco youth education centre.

Meanwhile, in central Macao, there are echoes of the former Catholic Relief Services headquarters, which played a pivotal role under the stewardship of the late Father Lancelote Rodrigues – who was affectionately known as ‘The Priest of Refugees’ – in the complex resettlement of thousands of Vietnamese refugees in the late 1970s.

But evidence of this period, when the region offered vital protection for people fleeing war and persecution, is slowly disappearing; both sites’ days are numbered, and whatever bricks and mortar remain will soon be repurposed or razed to the ground. There are no plaques or memorials, and the selfless work of those who supported and resettled refugees in Macao has largely gone uncelebrated.

Paul Pun, secretary general of Caritas Macau and president of the Association for the Relief of Refugees, senses a missed opportunity. Pun, who worked at a Macao refugee camp called Ilha Verde, says the territory’s progressive and humanitarian approach deserves to be commemorated through historical markers or a museum. “We have all the documents and photographs here [at the Caritas office]. What happened at Ka Ho was remarkable and we should teach others about the role we all played in helping refugees.”

A region in turmoil

Macao’s post-war relationship with refugees began in 1949 following the ascent of Mao Zedong’s Chinese Communist Party (CCP) and the founding of the People’s Republic of China. Within a decade, the CCP had implemented sweeping land reforms and a dramatic overhaul of the country’s economic and cultural systems, beginning with the Great Leap Forward in 1958.

Millions were executed or sent to re-education camps, while millions more died from malnutrition and starvation. Of those fortunate enough to escape, many travelled overland to Macao, which was then under Portuguese administration. According to volume five of the Cronologia Da História De Macau by Beatriz Da Silva, 758,916 refugees entered Macao in 1958. That same year, 715,423 refugees were resettled elsewhere – meaning only 43,493 people remained in Macao and integrated into society.

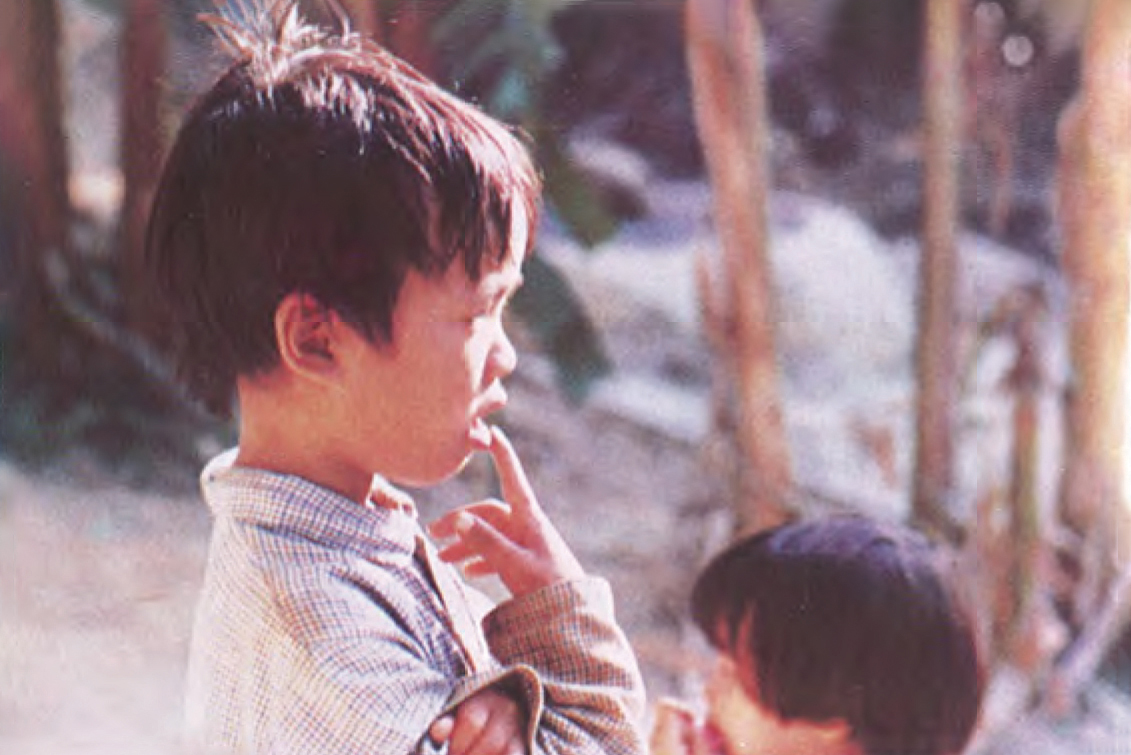

Further upheaval gripped the region as the 1960s and 70s wore on. Starting in 1975, a second wave of refugees began arriving in Macao, this time from Vietnam after the communist victory over the United States ended a bloody and protracted war that had killed some 2 million people. In the next few years, hundreds of thousands of Vietnamese fled the country by boat to avoid potential execution, re-education, or imprisonment by the communists who were now in power. Many also fled because they were suspected of collaborating with the American government or their proxies in Ho Chi Minh City (known then as Saigon).

To compound matters, China invaded Vietnam in early 1979 and a third wave of some 250,000 refugees (mostly Hoa people, ethnic Chinese who had settled in Vietnam centuries earlier) fled to Macao, Hong Kong, and other countries in Southeast Asia. According to the United Nations, between 1975 and 1995, at least 7,100 Vietnamese refugees arrived in Macao before being resettled in third countries, predominantly the United States, Canada, Sweden, Australia, and the UK. Only a handful remained in Macao.

Making progress

When refugees arrived in Macao, the Social Welfare Department and the UNHCR gave them clothing, food, toiletries, and basic kitchen utensils. They also assigned them to one of three camps: Ka Ho, Luís de Camões (both of which were run by Catholic Relief Services, or CRS) and Ilha Verde, which was operated by Caritas Macau. There was also an informal settlement where the Scout Association of Macau is currently located, near the Macau Jockey Club in Taipa, that temporarily housed more than 300 refugees, as well as another in Hac Sa Wan that housed 100.

In total, the camps cost around US$10 million (MOP 80.5 million) to build and maintain, with funds coming from the United Nations, the Red Cross, CRS, various religious groups, and the Portuguese-Macao government. In addition, the Catholic Diocese of Macau provided healthcare and educational needs.

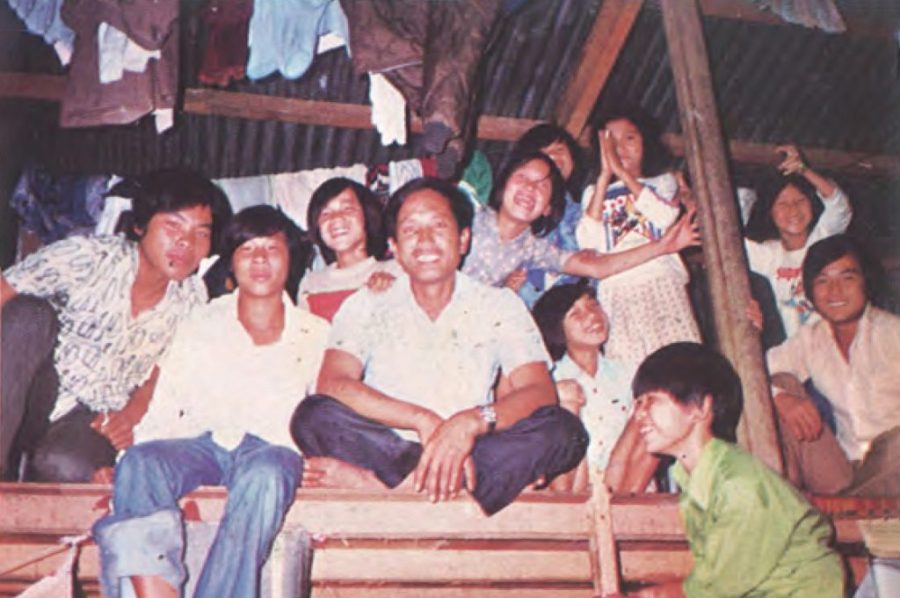

Ka Ho refugee camp, a former Portuguese military barracks on the northeast tip of Coloane, was the largest of the three, with around half a dozen 10-metre-long metal shacks that contained rows of bunk beds. The camp – which operated between December 1978 and July 1991 – was crowded and fenced off, but refugees had relatively unrestricted freedom of movement. “The refugees were not locked up and they were free to leave,” says Pun. “In this open environment they learned new skills, found work, and were able to better integrate with the local community.”

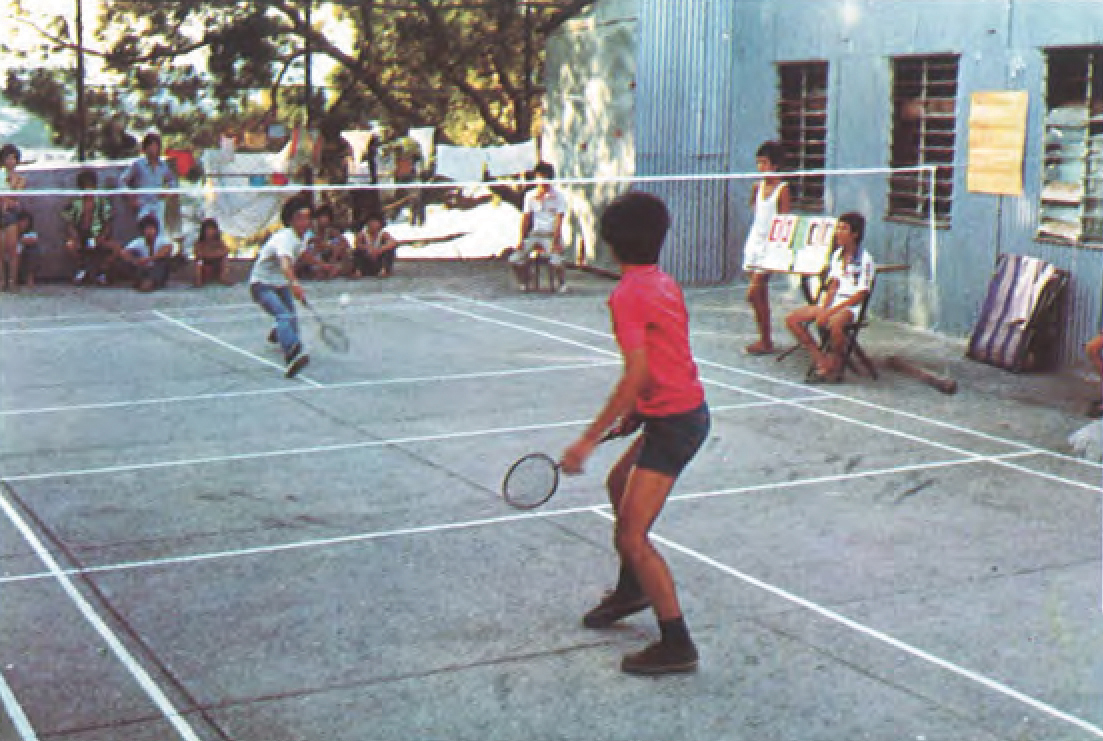

Looking at old photographs of Ka Ho camp, one is struck by the range of facilities and activities which were rare in that time period, if not today. Refugees had access to education and medical care, as well as a variety of recreational and educational activities. There was a tuck shop, a beauty salon, a carpentry workshop, communal televisions, a children’s playground, beach outings, swimming lessons, water polo, competitive football matches, table tennis, badminton, chess and athletics competitions, marriage ceremonies, a disco, music nights, Vietnamese cultural evenings, and annual Christmas parties.

More importantly, the camp took care of refugees’ health and hygiene, and there were opportunities to work for a modest wage, alongside the daily allowance of MOP 7 for single refugees (MOP 30 in today’s currency), MOP 13 for couples, and a weekly ration of rice in addition to regular meals in the canteen. A number of factories also hired refugees from the camps. For example, many women produced artificial silk flowers while men often worked in construction, engineering or electronics.

An unrecognisable Macao

A few years ago, Hoang returned to a very different Macao than the one he had left over three decades earlier. Macao is arguably more closed off with regards to its refugee policy than it was prior to the 1999 handover to the PRC, and is run predominantly on the casino, tourism and luxury goods; where Chinese refugees in their hundreds of thousands once flooded in, now its Chinese tourists.

Apart from a few hundred refugees who sought protection in 1999 when the Indonesian army invaded Timor Leste following an independence referendum, Macao hasn’t witnessed a refugee crisis of any great magnitude since the last Vietnamese were resettled in 1991.

Recognising the current turmoil in countries like Syria, Paul Pun says he would like to see Macao once again extend a hand. “We are a small place and letting in more people would be a good way to show the world that we care.” He says it’s “the right thing to do” and might encourage others to follow suit.

As a symbolic gesture, Pun says Macao should accept at least 100 asylum seekers and offer them full rights as refugees so that they can work and contribute to society or, at the very least, find a safe haven before being resettled in a third country. To put those figures in context, Germany accepted 1 million Syrian refugees in 2015 (around 1.25 per cent of its population). The decision continues to generate heated political and social debate, and for Macao to do the same would mean inviting around 8,000 refugees to resettle in the SAR.

Unlike Hong Kong, Macao has signed the 1951 Refugee Convention, which defines the term ‘refugee’, outlines the rights of displaced people, as well as the legal obligations of States to protect them. While the government processes individual claims, asylum seekers receive financial aid of around MOP 4,230 per month from the Social Welfare Bureau, as well as government housing. They are, however, prohibited from working or studying, unless they are granted official refugee status. There are currently no official refugees in Macao, and only a handful of asylum claims are being processed.

Though Hong Kong is not a non-signatory to the refugee convention, most asylum seekers choose to go to Hong Kong over Macao because it’s a much larger city with hundreds of direct flights globally, a UNHCR office, many diasporas and communities, and arguably more employment opportunities (both legal and illegal). That being said, Pun still hopes to draw on Macao’s legacy as a haven for refugees to create a safe, productive and welcoming place for forced migrants.

One of the women who made flowers was the mother of Michael Hoang. Hoang was born in Ka Ho refugee camp in 1984. Four years earlier, his parents had escaped the aftermath of war in Vietnam, found refuge in Macao and eventually married in the Ka Ho camp. Like many other refugees fleeing Vietnam, their journey to Macao was fraught with danger.

The small boats were packed with 50 refugees, and the ordeal was long and arduous – full of illness, fear, anxiety, and death. The UNHCR estimates that between 200,000 and 400,000 Vietnamese people died from overcrowding, piracy, disease, starvation, malnutrition, and storms whilst en route to countries across Asia. Hoang’s parents’ boat eventually arrived in Hong Kong, only to be redirected to Macao, something of a blessing given how well the city treated refugees at the time.

Hoang, now 37, works for a major media and telecommunications company in Toronto. Over the phone, he describes his parents’ life inside the camp. “The nurses, the administration staff, and Father Lancelote were all extremely good to us,” says Hoang. “And when the refugees were outside looking for work, the locals treated them like normal people. They didn’t think any less of them.”

When discussing this period, it’s difficult to overstate the role played by Father Lancelote, who passed away in 2013, in caring for refugees. Hoang’s parents described him as a thoughtful, generous individual who always saw the best in others: “You had all walks of life in the refugee camps. Some families weren’t educated, while some were suffering a great deal of trauma, but Father Lancelote always did his best to make the most of the situation and make sure we were all well-fed, housed, and had a purpose in life.”

The year Hoang was born, the family left Macao and resettled in Canada. Right before the Hoang family moved, Father Lancelote gave them money to help with the transition. “He didn’t have a lot of money himself, but that’s the kind of man he was.” Hoang believes that the Malaysia-born Portuguese Father Lancelote hasn’t received the credit he deserves: “The younger generation probably have no idea who he is and what he did for Macao. Maybe only the older generation do. It’s almost like he’s a forgotten memory.”

While the Ka Ho facility was progressive, it was still extremely challenging to live as a refugee – it was a dark period to be alive and many people had to fight to survive, according to Hoang.

“In terms of the 1970s and 80s, we’re talking about the aftermath of the Vietnam War. It was miserable. It was not a good time in Asia, economically or politically,” he says. “So many people were leaving their home countries, and Macao was a safe haven for people to get out of whatever situation they were in. But even then, it was no beach resort. You had hundreds of people showing up on the shores and filling up the camps, and you had these people working there thinking, ‘What will we do with all of them? What is the right thing to do?’”

Hoang says people like Father Lancelote, Paul Pun, and countless others, did the best they could to make the conditions bearable for thousands of people who were ripped from their homeland, hoping to begin a new life elsewhere. Fortunately for the Hoangs, and for others in the Ka Ho refugee camp, that reality eventually came to pass.

The past lives on

When it comes to legacies, Hoang and Pun are on the same page. The two men connected in 2015 when Hoang returned to Macao with his mother “to find my own identity,” as he puts it. Hoang says he identifies as a Canadian but coming back to Macao made him reflect deeply on what his parents went through. “When I went back there, I understood,” he says.

Both men believe that Macao’s unique role in caring for Vietnamese refugees, as well as other victims of war and persecution around the region, should be recognised as an example for modern society. “I definitely think the camp should be commemorated,” Hoang says, resolutely.

In terms of what memorialisation might look like, Hoang believes that it’s more about education than a physical commemoration: “It could be a day for the citizens or residents of Macao to celebrate, or it could be social programmes that educate people so the story becomes part of the system.”

“A lot of the people who worked there are heroes,” Hoang says. “And they did it because, for them, it was the right thing to do…That charity, that humanity, and the overall compassion of the people is still alive and strong. Unfortunately, they’re not recognised for it.”