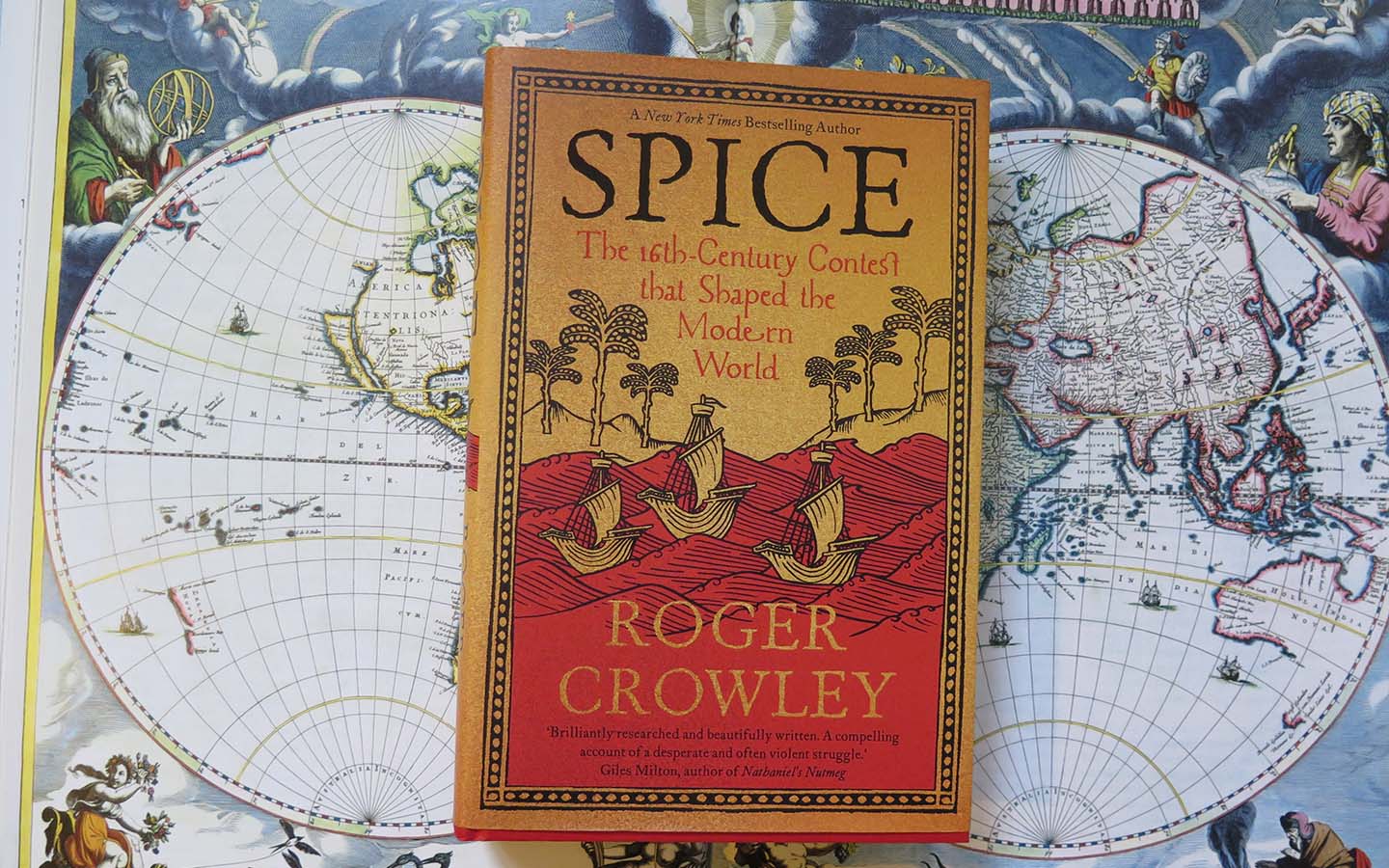

Centuries before Macao was recognised as a UNESCO City of Gastronomy, European explorers bound for the Spice Islands competed for consumable commodities worth more than their weight in either gold or silver. Written as a historical narrative spanning across six decades amid the Age of Discovery, Roger Crowley’s Spice: The 16th-Century Contest That Shaped the Modern World, chronicles the intense competition among Portuguese, Spanish, and even English navigators for oceanic trade routes that would eventually connect Macao to a maritime silk road.

“As we look into our kitchen spice racks, it is hard to imagine what the fuss was about,” the Cambridge educated historian, who previously authored Conquerors: How Portugal Forged the First Global Empire (2015), tells Macao News.

[See more: A snapshot into 1930s Macao: the photographic legacy of Melville Jacoby]

Under the 1494 Treaty of Tordesillas, the crowns of Portugal and Castile divided the world into two spheres. The Portuguese headed east, sailing around the southern African coast while the Spanish expanded westward into the Americas. The division later sparked disputes over prized archipelagos in the Pacific Ocean, valued for their production of nutmeg and cloves.

Without any input from the local inhabitants, each European power understood that the visibility of armed ships and locally established garrisons held more sway than any signed document. The Portuguese and Spanish would clash throughout the Maluku Islands in present day Indonesia, finding themselves engaged in deadly proxy wars and a power structure among tribal loyalties that they did not understand, Crowley writes.

Visible relics in Macao

The portrayal of late 16th-century Macao undertakes a supportive role in Spice and several names may sound familiar to a local audience. Captain-general Leonel de Sousa – who gave his name to the Rotunda de Leonel de Sousa, located in front of Governor Nobre de Carvalho Bridge – is discussed at length. So too is Tomé Pires, the early 16th-century apothecary and author of Suma Oriental, whose legacy lives on in Rua de Tomé Pires – a short walk from the Red Market where once sought-after produce from around the world is sold every day.

In 1555, England’s Company of Merchant Adventurers to New Lands, an early joint-stock trading company which embarked on a northern route to Asia, departed just days before the death of King Edward VI. The company’s joint-stock structure would become an earlier blueprint for the British East India Company, which later used Casa Garden as its offices in Macao, located adjacent to the Old Protestant Cemetery where many trading merchants are buried.

Beyond iconic landmarks, Macao exists as a living sequel to Spice. For the author, his interest was not just about the exploration of valuable islands, but also the attempts to control them and the subsequent events that followed. His book resonates at a time when Macao is seeing renewed interest in its food history and culinary heritage at a time when the economy is seeking to diversify from gambling with broader tourism offerings. Through this lens, Spice becomes the city’s prequel, reminding how Macao’s historical flavours long existed before the city itself.

[See more: Unveiling hidden histories: American traders’ glimpses into old Macao]

Back in 2021, Macanese cuisine was celebrated as part of China’s National List of Representative Elements of Intangible Cultural Heritage, in part acknowledging the maritime routes of the previous four centuries. Last week, the city hosted the International Gastronomy Forum, which explored the vibrant world of spices, fusion cuisine, and cultural exchange under the theme The Spice of Life: Macao’s Culinary Connections. The event highlighted the creativity that unites global communities and preserves food traditions.

While Manila remained the hub that linked the Asian spice trade to the Americas across the Pacific, Macao was a component in the supply chain. Historically, “I tend to think of Macao as a Venice of the East: a small island with no natural resources whose only role was solely to trade,” the author says, describing Macao’s galleons and bulk transport carriers that spanned the seas from Goa to Japan, providing an intermediary linkage between the city and Manila.