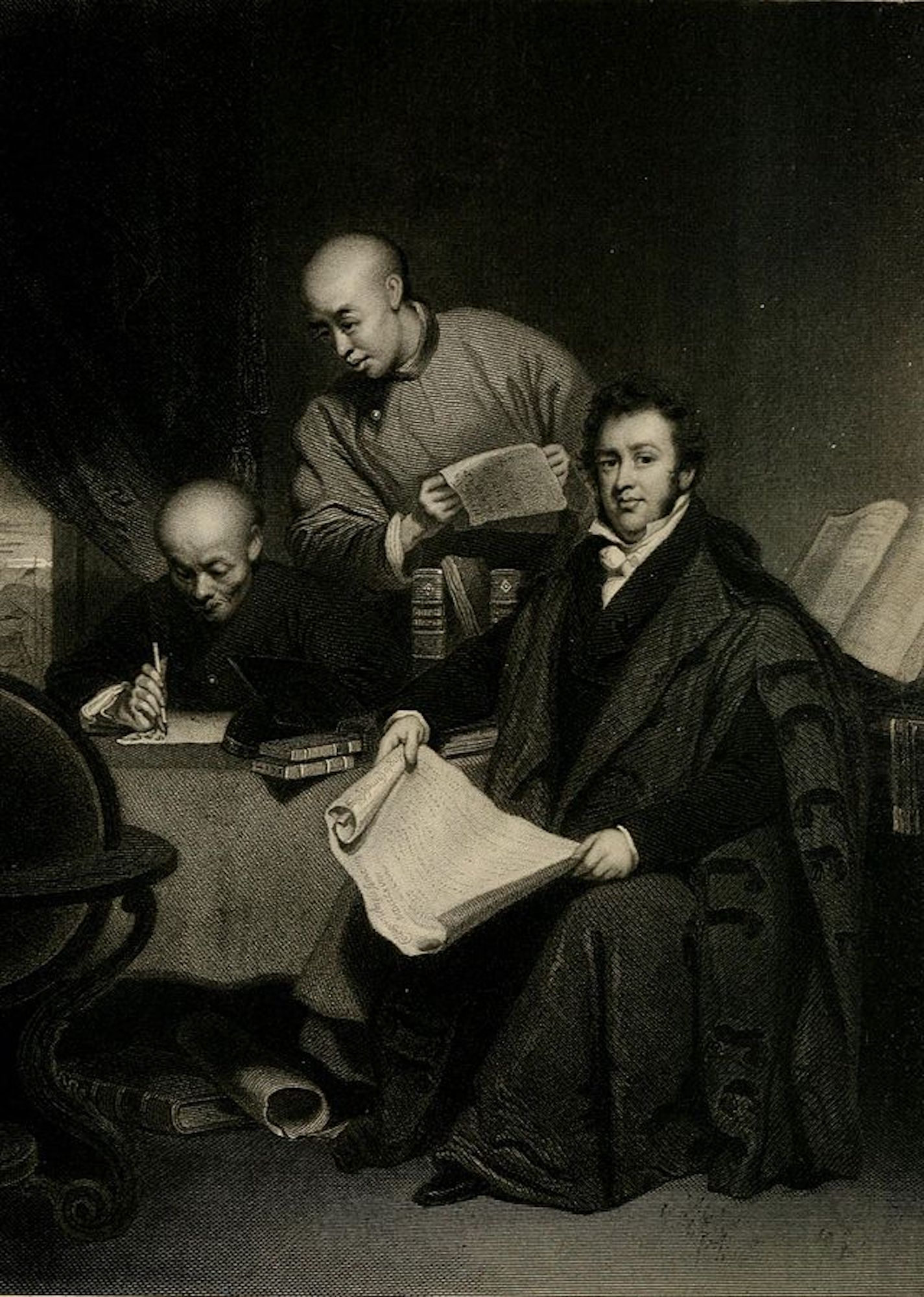

Robert Morrison was a fearless, crusading pioneer, a gifted linguist and lexicographer, a family man – he fathered eight children – and a man of God. He was also very much a man of his times.

Seized with a desire to bring Christianity to the earth’s largest population in the early 19th century, he travelled halfway round the world from his native England, established himself in Macao in the face of stiff official opposition, and laid the foundations for a dynasty that continues to this day.

He was also far ahead of his times, as in subsequent years his missionary work and superlative efforts as a translator led to a greater understanding between different races and East and West.

Morrison’s name is not so widely known today, but until the pandemic brought travel restrictions every year thousands of Chinese Christians from all over the world come to the Macao Protestant Chapel and Old Cemetery in Santo António parish to pay their respects.

Morrison died in 1834 and is buried in the cemetery next to the chapel, beside his wife, Mary, and two of his children, having spent most of his life in southern China.

His was a life made all the more remarkable given his humble origins. He was the first Protestant missionary to Asia, the first person to translate and publish the Bible in Chinese; and the first to convert and baptise Chinese people.

“He is an unofficial saint to the Chinese churches in the diaspora,” says the Reverend Stephen Durie, the Australian minister of the chapel, whose regular congregation now meets in two venues – Morrison Chapel and Macau Anglican College – and numbers around 200. “Believers come here from all over the world to pay their respects at Morrison’s grave. This place is particularly significant to Protestant Chinese Christians, as the birthplace of the Chinese Protestant church in the modern era. The church in China is said by some to be the fastest growing in the world. You can say Morrison started it all.”

The stained glass above the altar features four Chinese characters, first translated by Morrison: “In the beginning was the Word”. They are the opening words of the Gospel according to St John, and also serve as a pun, indicating that, in this place, the words of God began for the Chinese people.

Humble beginnings

Morrison was born in January 1782, the youngest of eight children of a Scottish farm labourer who moved to Newcastle in north-east England to work in the shoe trade. Morrison followed his father into the business, working up to 14 hours a day. A devout Presbyterian, he decided to become a missionary before he was 20.

A minister proposed that he work in China, whose population of 350 million was twice Europe’s. With a third of the world’s inhabitants, it was a tempting prospect for a young man fired with Christian ideals, as it contained only a small number of Catholics, and no Protestants.

Morrison settled down to study Chinese, a lifelong passion which in time would make him one of the leading Western experts.

But reaching China presented an enormous challenge. The East India Company, the principal British company involved in China trade, whose headquarters were in Macao, refused to carry missionaries on its ships. So Morrison left Britain in January 1807 and sailed to New York, reaching Macao in September on an American vessel.

It’s said that shortly after landing he was asked whether he expected to have any spiritual impact on the Chinese. Came the reply: “No, sir, but I expect God will!”

The exchange typified Morrison’s determination, and the suspicion that made his early years in Asia so difficult. The Roman Catholic authorities in Macao resented the arrival of a Protestant minister, while the government in Beijing banned its people both from any involvement with missionaries and teaching Chinese to foreigners.

Prayers in Chinese

Morrison, who had little in the way of funds, divided his time between Guangzhou and Macao, improving his Chinese as best he could and keeping his books out of sight so that no one would report him. He began work on an English-Chinese dictionary and said his prayers in Chinese.

His luck changed on 20 February 1809 – the day he got married and was appointed translator to the British East India Company, with a substantial salary of 500 pounds a year – worth perhaps 40,000 pounds nowadays. This gave him status, a measure of protection and the opportunity to improve his Chinese legally. Away from work he started preaching, which he considered the most important reason for going to China.

On 16 July 1814, he baptised the first Chinese convert to Protestantism, Choi Kou; an Anglican school in northern Macao bears Choi’s name.

The following year, he published a grammar of the Chinese language and, between 1815 and 1823, a six-volume Chinese dictionary and the Bible in Chinese in 21 volumes. The dictionary was published in Macao and the Bible in Malacca, because it was illegal to publish it in China.

These volumes were of enormous historic significance in making the scriptures available to the citizens of the world’s largest country and as a bridge of understanding between East and West. Morrison printed the Bibles in small editions which people could carry easily in their pockets and avoid detection; having Christian literature was against the law in imperial China.

Morrison spent 1824 and 1825 in England, where he presented his Chinese Bible to King George IV and was warmly received in society. He brought a collection of nearly 10,000 Chinese books, which he had built up over many years, with the aim of giving it to the nation. They are now in University College London.

By this stage Morrison, never one to sit back for very long, had also created an Anglo-Chinese college to introduce Western and Eastern culture to students from all round the world and prepare people to spread Christianity in China. Since he could not set up such an institution in mainland China or Macao, he opened it in 1818 in the British Straits Settlement of Malacca; it was the world’s first Anglo-Chinese college. It later moved to Hong Kong and continues today, with the name Ying Wa (Britain-China) College.

In 1826, Morrison returned to Guangzhou, to find relations between the British East India Company and the Chinese government deteriorating. But the church he had founded was growing, with an increasing number of converts, missionary students and religious material in Chinese.

He died on 1 August 1834 in Guangzhou, at the age of 52. His body was taken to the Protestant cemetery in Macao and buried next to his wife, Mary.

The Chinese inscription on his tomb reads: “It is said that man may obtain immortality in this world only by his immortal words and actions. Robert Morrison is a great example of such a man. When he came to China, when he was still young, he studied diligently and worked arduously, thus completely dominating the Chinese language, both written and spoken.”

Ironically, Robert Morrison never preached at the chapel which bears his name. It was Anglican whilst he was a Presbyterian lay missionary.

A house of God

The chapel was built on land acquired in 1821 by the East India Company. Previously, the former Portuguese government had forbidden the burial of Protestants within the city walls. But the death of Mary, Morrison’s first wife, persuaded the government to change the rule on the condition that the chapel had no bell and was surrounded by a wall.

The government wanted to keep the Protestant community as small as possible. By 1921, white ants had destroyed the original structure. It was replaced by a new building, which was dedicated in 1922 as a House of God, not an Anglican church.

Its most famous minister was Rev Florence Li Tim Oi from Hong Kong, the first woman priest in the Anglican Church. She played an outstanding role during World War Two, when Macao was neutral, and attracted a flood of refugees. “She served and helped the poor and risked her life to conduct religious services in China during World War Two,” says Rev Durie. “She was a remarkable person and a faithful priest.”

Morrison started what became one of the biggest missionary endeavours in history, inspiring thousands of others to follow him to China.

After the foundation of the People’s Republic of China in 1949, foreign missionaries were expelled and religion totally reorganised. The government set up the Chinese Catholic Patriotic Association (CCPA) for the Catholics and the Three-Self Patriotic Movement for the Protestants.

The CCPA does not accept the authority of the Vatican and appoints its own bishops; likewise, the Three-Self Movement is self-governing and appoints its own ministers. In the last 20 years, there has been unprecedented growth, in both the official and unofficial churches and especially in the Protestant churches. Foreign estimates of the number of Christians in China today go as high as 80-100 million.

Morrison’s pioneering work has reaped handsome, far-reaching rewards.